Lakhimpur: Banveerpur’s Hindu-Muslim and Sikh communities have very different stories on Ajay Mishra

The first story is on how he solves all their problems. The second is about how everyone is scared of him.

“I have four Sardar classmates. This week they did not come to class,” said Payal, a student of Class 6. Anshu, who studies in Class 5 in the same school, said that of the four Sikh children in his class, only two showed up.

Anshu and Payal study at the Mahishadevi Saraswati School, attended by most of the children in Lakhimpur Kheri’s Banveerpur village, the hometown of Ajay Kumar Mishra, minister of state in the ministry of home affairs. With grades up to Class 10, the school was constructed by Mishra’s father 40 years ago in 1981.

Banveerpur, hardly 10 km from the Nepal border, is one of the easternmost villages within Lakhimpur Kheri, the largest district of Uttar Pradesh. For the past week, this village has been the epicentre of a political battle.

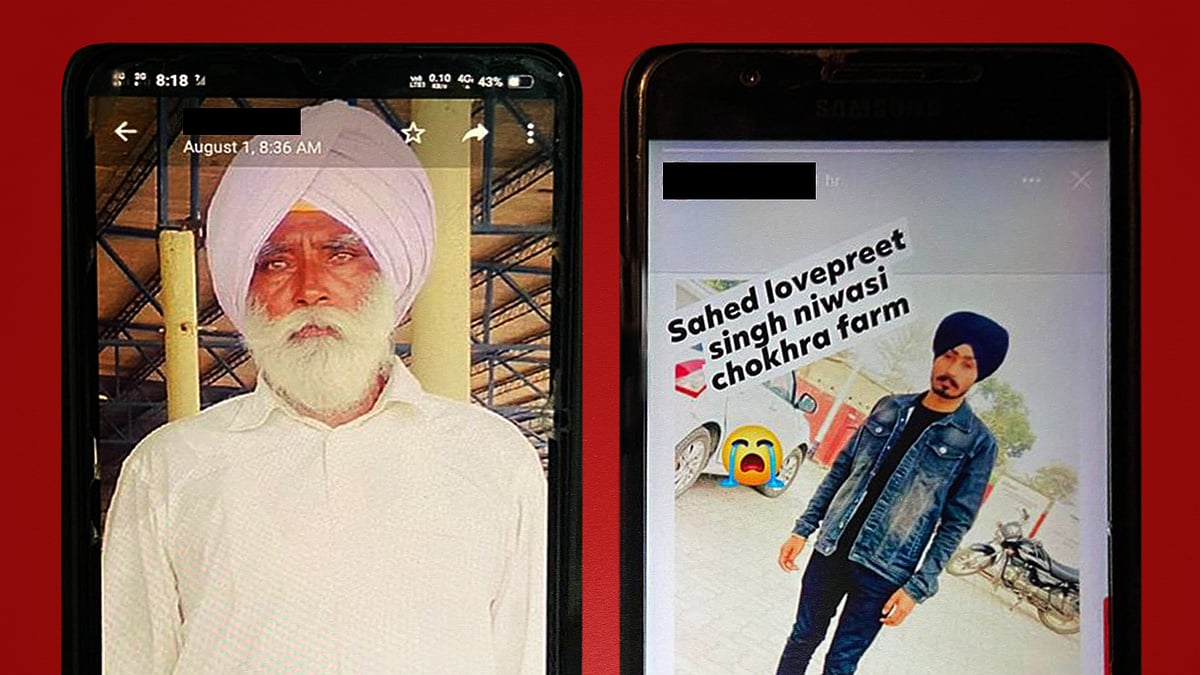

On October 3, three vehicles rammed into a crowd of protesting farmers, the incident and the ensuing violence killed eight people: four farmers, two BJP workers, a driver and a journalist. Two of these three cars belong to Ajay Mishra, 61. Multiple eyewitnesses allege that Ashish Mishra, the minister’s son, was in one of the vehicles.

After much public outrage and political pressure, Ashish Mishra was arrested on October 9.

What began as an incident between farmers and the BJP has now spiralled into a simmering animosity between Hindus and Sikhs. The tension is palpable in the minister's own village.

Support Independent Media

The media must be free and fair, uninfluenced by corporate or state interests. That's why you, the public, need to pay to keep news free.

Contribute

Locating the Mishras in their hometown

Banveerpur, which falls within Nighasan assembly constituency, is a village with a population of about 9,000. Akash Mittal, 31, the village pradhan, explained that there are around 8,000 Hindu voters, 600 Muslim voters and 300 Sikh voters. The village is further divided into three areas: Ramnagar, Munjha and Daraboji.

Most of the Hindus and Muslims live in Ramnagar and Munjha, and the Sikhs largely live in Daraboji. While the Hindus and Muslims live in a cluster, with houses sharing compound walls, the Sikhs, who are large land owners, have constructed their homes in the middle of their fields, away from the rush of the village.

So far, Akash said, the village has only had Hindu pradhans; there has never been a Muslim or Sikh pradhan in Banveerpur. He explained that the Sikhs moved to Lakhimpur after Partition and settled in the area when they found that land prices were very cheap.

Among Banveerpur’s thatched-roof kuccha houses and mud roads, Ajay Mishra’s house stands tall. With a fresh coat of paint, it’s a sky-blue, multi-storied building that towers over the rest of the village. This is where the minister and his wife Pushpa brought up their three children: Ashish, Abhimanyu and Rashmi.

Abhimanyu, 37, is a pediatric doctor in Lakhimpur city. Rashmi also lives in Lakhimpur city, where she works at the Lakhimpur Kheri Urban Cooperative Bank.

Ashish, 38, is a BSc graduate who shadows his father.

The house is currently empty. Six policemen stand guard around it, while the police summons to Ashish Mishra are pasted on the gate.

While most villagers had much to say about “Monu bhaiya” (Ashish) and “doctor saab” (Abhimanyu), they struggled to recall the name of the minister’s daughter. “We haven’t seen her much,” most of them said.

Monu Bhaiya’s political aspirations are not subtle. The roads to Banveerpur are lined with painted walls that read “Abki baar, Monu bhaiya sarkar”, parroting prime minister Narendra Modi’s 2014 election slogan of “Abki baar, Modi sarkar” – one of the most popular election phrases in the history of Indian elections. While the walls are painted with Monu bhaiya’s names, the hoardings largely feature his father.

In Banveerpur, Ajay Mishra is fondly called “Teni Maharaj”, not just because he is from the upper caste but also because he is aggressively worshipped.

“We don’t vote for a party. We vote for Teni Maharaj,” said Ram Sagar, 34, a farmer in the village. “Even if he shifts to Congress or Samajwadi, he will still get our vote.”

At the entrance of the village, exactly opposite village pradhan Akash Mittal’s house, is a rice mill, the Sri Ambika rice mill. It’s the first one to be built in Banveerpur and was constructed 25 years ago by Ajay Mishra’s father Ambika Pratap Misha.

This mill is also where the family’s politics were born, Akash said. “Election speeches, debates, events, everything that made the Mishra family enter politics began in this mill.”

Ajay’s foray into electoral politics began in 2005 when he fought his first panchayat elections. Until then, outsiders from other villages would come and campaign in Banveerpur for votes. Ram Sagar said, “When Teniji contested, one slogan was made very popular: ‘Bahri bhagao, kshetriya banao’.” Chase the outsiders, elect an insider.

Nevertheless, Ajay lost his first election.

In 2010, he contested the election yet again and won the post of village pradhan. In 2012, he became the MLA of Nighasan constituency. In 2014, he successfully climbed the political ladder and became a Member of Parliament – a feat he repeated in 2019.

According to the Hindus and Muslims who spoke to Newslaundry, “Teni Maharaj” had done a lot for the development of the village. Most residents are farmers, and the rice mill plays a crucial role in their lives.

“Before this, we used to have to travel long distances with our harvest,” said Mohammad Mubeen, 50. “But because of Teniji’s mill, our lives have changed. Apart from this, his rice mill has given employment to so many people here.”

When the village’s Muslims are asked about the minister or Ashish Mishra, they point towards a mosque. “See this mosque?” they said. “Teniji ensured we were able to construct it.”

The Muslims live in a cluster about 100 metres away from Ajay Mishra’s house. In the midst of this cluster is a temple, opposite which is the mosque. Newslaundry was told there are no Hindu-Muslim tensions here, and both “Teni Maharaj” and “Monu Bhaiya” are loved by both communities.

“Monu Bhaiya is very much into sports,” said Marouf Khan, 31. “We all played volleyball and cricket together when we were kids.”

When asked why Banveerpur’s Muslims and Hindus are so fond of Ajay and Ashish Mishra, the answer is unanimous: the janata darbar, or people’s court, held by the father-son duo.

Mubeen Ahmed explained that when Ajay Mishra lived in Banveerpur and before he got busy with his duties as a minister, he would open the gates of his home every morning at 7 am. “People would gather; villagers would bring their problems and conflicts to him,” Mubeen said. “He would listen and give a verdict.”

Akash Mittal elaborated that most often, these conflicts revolved around property issues, marital problems, and petty crimes. “We wouldn’t even have to go to the police station. He would help solve these issues quickly,” he said. After Ajay became a union minister, Ashish presided over these courts.

The Muslim community in Banveerpur echoed the Hindus when asked about their political affiliations. “Yes, the BJP might be anti-Muslim but we don’t vote for BJP, we vote for Teni Maharaj,” they said.

Sikhs in silence

But the Hindus and Muslims who so readily gushed over “Teni Maharaj” fell silent when asked about the Sikh community.

“That was a protest by Sardars not farmers,” said Ram Sagar. “We’re also farmers right? We’re not protesting, are we? So why should we call that a farmers protest?” Ram was referring to the black flag protest by some farmers on October 3, scheduled to coincide with a wrestling match attended by Ajay Mishra in Banveerpur. Soon after, the three vehicles rammed into the group of protesters.

Mubeen Ahmed was also angry with the Sikhs. “They just want Khalistan,” he said.

Khalistan, in this context, does not translate to a separate nation for Sikhs as it did in the 1970s. In Banveerpur, when locals said the Sikhs are “Khalistanis”, what they mean is that the Sikhs are attempting to dominate them.

“Look at them. Their fields are so large, they surround the entire village,” said Mohammad Marouf. “They are a small community here but they’re rich. They want to try and control us. This whole farmers’ movement is not about farmers, it’s about Sikh dominance.”

In Banveerpur, the lives of the Hindu and Muslim groups are deeply entangled. They live next door to each other, the women are close, their children play together, and there’s a general sense of community. Whereas the Sikhs, who live a little away from the Hindus and Muslims, are not as involved in village life.

“We speak to them for work, for water, or about their crops,” said Mubeen. “Otherwise, things are pleasant. We never had anything against them but we’re not close to them.”

The current anger towards the Sikh community seems to have sprouted from the incident that took place on October 3. Prior to this, the villagers claim there was no tension. But since then, there has been a tense silence between the Sikhs and the rest of the village.

“Nobody has dared to break this fragile silence,” Mubeen said. “We don’t want to trigger a fight and neither do they. But there’s a very strong fear that something might happen.”

Teni, the terror

The Sikhs in Banveerpur have a very different story to tell about “Teni Maharaj”.

“In 2014, we too voted for him because we believed in the BJP. We didn’t vote for Teni, we voted for BJP,” said Harwinder Singh, 32, a farmer. “That was the Modi wave.”

But soon after, especially once Modi’s second term began, Harwinder said that most of Banveerpur’s Sikhs began to get disillusioned. When asked why, he pointed to rising fuel prices, the BJP’s Hindutva agenda, and the farmers' protest.

The Sikhs that Newslaundry spoke to said that they do not attend the janata darbar hosted by Ajay and Ashish Mishra. “We have our own meetings and resolve issues by ourselves. We don’t go to him or his son,” said Chandra Bahn Singh, 48, a farmer who also runs a shop in Banveerpur.

After a pause, he asked this reporter, “So, did you speak to the other villagers? Did they say how much they love Teni?”

When Newslaundry confirmed this, he said, “You will not find a single person in this village who will speak against him. People are terrified of him and his son.”

Another Sikh resident standing nearby chipped in, “ Ashish Mishra is a complete dabang type neta.”

What made the Mishras such rogues in their eyes?

Most of them pointed to a murder case lodged in 2004 against the union minister, which remains pending in the Allahabad High Court. Jarnail Singh, 50, a Sikh farmer, explained that there have also been a number of incidents where “Ajay Mishra and his men” would allegedly pick up villagers who spoke against them, lock them in a room, and thrash them.

Ashish Mishra, they said, was no different. “Ashish had all his father’s qualities and more. He was a complete rogue,” Jarnail said.

When asked if any particular incident stands out in their memory, the Sikhs said that most people are scared and would not want to talk about it. When asked again, some of them hesitantly pointed toward the neighbouring village of Ganganagar.

“Go there, you’ll find him. He is still alive but Teni almost killed him,” said Chandra.

‘Humiliated and slapped’ by Ajay Mishra’s men

Ganganagar is around four km from Banveerpur. Here, Newslaundry met Prabhjit Singh, 65. Prabhjit suffered polio at a very young age and lost the use of his left arm. His wife is blind. The couple have two daughters and a son.

Prabhjit is not his real name; he asked Newslaundry to keep him anonymous.

As soon as we asked him about Ajay Mishra, Prabhjit went into his house. He returned with a notebook which he opened and pointed at a date. August 16, 1990.

In 1990, Prabhjit was around 40 years old. On the morning of August 6, he said, some of Ajay Mishra’s men were trying to pump excess water from their farm into his.

“So, I along with some people from here asked them to stop it,” he said.

At 6 pm, he went to have a bath under an open tap a few metres from his house. “It was getting dark,” he said. “ I finished my bath. I was naked with just a loincloth around me. That’s when Teni’s men came and caught me. They then went and dragged my brother out of the house.”

He continued, “From there, they dragged us through the fields and took us to Teni’s house. I was completely naked and bleeding by the time they dumped us in front of Teni.”

For the next few hours, Prabhjit alleged that he and his brother were “humiliated and slapped” by Ajay’s men, who threatened him and told him to never again speak against the now minister. “Teni saw all of this being done to me,” said Prabhjit. His leg still carries a wound from this attack 31 years ago.

By 11 pm, the men took Prabhjit and his brother to the edge of Banveerpur, he said. “From there, my brother and I somehow came home. I told people in my community and the next day, we went and filed an FIR at Tikunia police station.”

Prabhjit showed Newslaundry a torn and tattered copy of the complaint, with only bits of pieces of it left. When Newslaundry sought a copy of the FIR from the Tikunia police station, station house officer Balendu Gautam said, “We don’t have copies of FIRs that old. And if the case reaches an agreement, you will not find it anyway.”

Prabhjit said that a month after he filed the FIR, Ajay Mishra’s men “forced” him to sign a piece of paper. “I don’t know what it said,” he said. “They didn’t give me a copy either. I never heard about my case after that.”

The other Sikh villagers also corroborated what Prabhjit said.

“I was very young but I remember the incident so clearly,” said Chandra Bahn Singh. “It was so scary. We know that he filed an FIR after that but then nothing happened. It was like a lesson for everyone in the village. It was Ajay Mishra’s way of saying, ‘See, this is what happens if you speak against me.’”

Meanwhile, Prabhjit and his family are still haunted by what happened. “He can do anything,” Prabhjit said, referring to the minister. “His son is also just like him.”

Conclusion

Station house officer Gautam was transferred to Tikunia police station on September 22. This is the police station that first investigated the violence of October 3.

“This is the first time I’m handling such a big case,” Gautam said. “I’m quite scared, to be honest.”

According to Gautam, while “Teni Maharaj” has “multiple cases” against him, his son Ashish Mishra does not have a criminal record.

Despite the current silence in the village, Sikh residents believe that if Ashish Mishra gets out on bail or is declared innocent, and if the union minister does not resign from his post, then protests will be organised in the area by the farmers’ movement.

“At the moment, we can’t show our anger because we’re small in number,” said Chandra Bahn Singh. “We still have to live here. If we protest and Monu comes back free, our lives will become hell.”

But the Hindu and Muslim residents claimed they will do whatever it takes to support their “Monu Bhaiya” and “Teni Maharaj”.

And so, the peace of this village now seems to dangle on the court’s verdict on Ashish Mishra’s role in the October 3 violence.

‘Aren’t we also farmers?’: Families of BJP workers killed in Lakhimpur deal with grief and anger

‘Aren’t we also farmers?’: Families of BJP workers killed in Lakhimpur deal with grief and anger Two farmers attended their first ever protest in Lakhimpur on October 3. It was also their last

Two farmers attended their first ever protest in Lakhimpur on October 3. It was also their last

Power NL-TNM Election Fund

General elections are around the corner, and Newslaundry and The News Minute have ambitious plans together to focus on the issues that really matter to the voter. From political funding to battleground states, media coverage to 10 years of Modi, choose a project you would like to support and power our journalism.

Ground reportage is central to public interest journalism. Only readers like you can make it possible. Will you?