The truth behind Modi government’s “all is well” GST narrative

The Modi government will like you to believe that GST has been a great success, but it’s far from the truth.

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) has just completed one year in India. The Modi government wants the nation to believe the new tax has been a great success—not surprising, given this government’s marketing orientation.

But how true is that? Let’s look at it point by point.

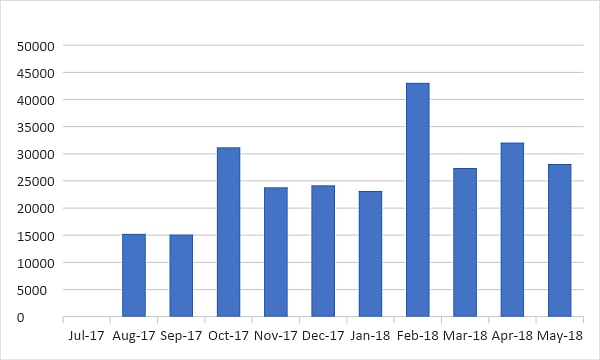

1) Look at Figure 1, which plots the GST collections of the Central government (or what is referred to as central GST).

Figure 1:

Source: Comptroller General of Accounts

The GST collections in each of the months between March 2018 and May 2018 has been lower than the collection in February 2018. In 2018-2019, the Central government hopes to earn ₹6,03,900 crore from central GST. This works out to ₹50,325 crore per month on an average. The collections in April and May 2018 were ₹32,089 crore and ₹28,119 crore, respectively. This is way below the target of ₹50,325 crore per month.

How does this make GST a success, when the government is not able to achieve the target it set for itself?

2) An impact of the government’s inability to meet the GST target can be seen in decisions made in the recent past. The Life Insurance Corporation of India is buying 51 per cent stake in IDBI Bank—which is basically the worst performing public sector bank—with bad loans of nearly 28 per cent. This means that ₹28 out of every ₹100 loans the bank has given are not being repaid.

In order to keep the bank going, the government has had to invest money in it over the years. Now with GST collections not being anywhere near the desired levels, the government has had to look at other ways to keep IDBI Bank going. Hence, the sale to LIC. With LIC now being the majority owner of the bank, it will have to invest money in the bank. The government’s expenses will come down to that extent.

Essentially, the policyholders of LIC will finance a junk bank like IDBI.

Over and above this, there has also been a lot of talk about selling the Air India building in Mumbai to Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust. All this wouldn’t have been happening if the Central government’s GST collections had been anywhere near the target.

3) In the last few years, Indian merchandise exports have taken a hit. They have fallen as a proportion of the GDP since 2014-2015, after Modi came to power. In 2016-2017, the exports to GDP ratio was 12.1 per cent. In 2017-2018, it fell to 11.7 per cent. A major reason for this is because exporters did not get GST refunds on time, which created a working capital problem for them. These are problems that could have easily been thought through at the very beginning, before the system was implemented.

4) The fundamental problem of the Indian GST system having too many rates continues. India has four non-zero rates of tax when it comes to GST: 5, 12, 18 and 28 per cent. (Actually, it has six non-zero rates of tax, given that gold is taxed at 3 per cent and precious stones at 0.25 per cent). Over and above this, there is a special cess on certain goods categorised as luxury and sin goods. Hence, we have many rates of GST.

The prime minister defended this recently by saying that milk and Mercedes cannot be taxed at the same rate. Milk is not taxed under GST. It’s a pity that no one brought to the prime minister’s notice that while diamonds are taxed at 0.25 per cent and gold at 3 per cent, sanitary napkins are taxed at 12 per cent.

The situation reminds me of a couplet by Wasim Barelvi, the greatest Urdu poet alive, who once said:

“Garib lehron par pehren bithaye jaate hain

samundaron ki talashi koi nahi leta.”

5) It doesn’t take rocket science to understand that the greater the number of rates, the more complicated the system. And who benefits from a complicated system? Bureaucrats and chartered accountants.

India Development Update, published by the World Bank in March 2018, points out that only four countries in the world, other than India, use four or more rates of GST. This is from a sample of 115 countries. These four countries are Pakistan, Ghana, Italy and Luxembourg.

In the sample, 49 out of the 115 countries use a single rate, and 28 countries use two rates. India is clearly in a minority here. But data probably doesn’t go well with political rhetoric.

6) The top rate of tax at 28 per cent—without taking the different cesses into account—is the second highest in the world. Obviously, higher rates of tax and tax evasion have a very high rate of correlation. This is something that should be well understood in India by now, given that the black money problem started because the marginal rates of tax hit as high as 97.75 per cent in the early 1970s.

7) The Harmonised System of Nomenclature (HSN)—which allocates codes for every conceivable good—runs into 438 pages and has 18,306 entries. Bureaucrats would have sat and thought through this and come up with every conceivable product category that they could think of. It would have been simpler to have two rates of taxes, one for goods and one for services. Of course, this would have meant a simpler system. And what would bureaucrats have done then?

Despite this detail, there has been confusion regarding the categorisation of some goods, as shown in many news items appearing over and over again.

8) The GST council has put out nearly 160 notifications till date. This includes tax and rate notifications. This is another point that shows the complicatedness of the system. It must be said here that the rate of issuing notifications has fallen during 2018.

9) One nation one tax—that was how GST was marketed. But it’s nowhere near that. Multiple GST numbers are required by businesses with a presence in one or more states. Multiple GST returns also need to be filed. This doesn’t help the ease of doing business. For a system which was built from scratch, this is a major flaw. Experts have now recommended that at least all the GST numbers of a single business be mapped to one login-id.

10) The GST website does not allow users to make changes. If you make a wrong entry while paying the taxes for a particular month—for example, you swap the entries for state GST and integrated GST—there is no way of correcting this.

11) Continuing with GST being marketed as “one nation one tax”, the e-way bill provisions have been made mandatory from April 1, 2018. While the e-way bill provisions for interstate movement of goods (i.e. between states) are uniform, the same cannot be said about provisions regarding the intra-state movement of goods (i.e. within a state). This again creates problems for businesses operating across multiple states.

Of course, there is no denying that India needs GST. But clearly, things could have been done in a much better way.

While the government may want us to believe that GST has been a substantial achievement, that is not the case. Given that a new system was designed from scratch, it is a clear case of an opportunity lost to do things well.

How do you explain all the song and dance happening around the so-called success of GST? For such situations, Mirza Ghalib had a couplet:

Bazeecha-e-itfal hai duniya meray aage

Hota hai shab-o-roz tamasha meray aage

(The world is a children’s playground before me

Night and day, this theatre is enacted before me).