Why a higher MSP is no solution to agriculture distress

The MSP policy is a huge distortion on the economy and needs to go.

News of agricultural distress has been hitting the media for years now. Governments, present and previous, haven’t come up with any structural changes to deal with the same.

The one thing that they have done is to play around with the minimum support price (MSP) policy. The government declares an MSP for 22 agricultural crops through the year.

The original idea behind the MSP was that it should act as a floor price. The assurance was that the price of a commodity would not be allowed to fall below a certain level, even if there was a bumper crop. Over the years, the MSP has become the maximum price that a farmer is likely to earn on his produce. (I dealt with this in detail here.)

In the budget presented in February this year, the finance minister Arun Jaitley had said: “In our party’s manifesto it has been stated that the farmers should realize at least 50 per cent more than the cost of their produce, in other words, one and a half times of the cost of their production. Government have been very much sensitive to this resolution.”

He had further said: “Our Government works with the holistic approach to solving any issue rather than in fragments. Increasing MSP is not adequate and it is more important that farmers should get full benefit of the announced MSP. For this, it is essential that if the price of the agriculture produce market is less than MSP, then, in that case, Government should purchase either at MSP or work in a manner to provide MSP for the farmers through some other mechanism.”

I will not debate here whether the government is actually offering an MSP which is 1.5 times the cost of production of the farmer. Nevertheless, it is more or less clear here that the government hopes to fight agricultural distress through the higher MSP route. The idea is to ensure that all farmers get paid an MSP on their produce and if they don’t, they get adequately compensated for it.

The MSP policy was first started in the mid-1960s to incentivise the Green Revolution and has been around for more than five decades. And it hasn’t worked. Now, the hope is that doing more of something that hasn’t worked, will work.

This cynicism apart, let’s look at the reasons why the MSP policy to compensate the farmer will not work.

- The government currently buys rice and wheat directly from the farmers. It is an exercise of mammoth proportions and is executed by the Food Corporation of India and other state procurement agencies. Over the years, the government has also started to buy pulses, cotton and oilseeds. Given the fact that it buys a limited number of crops, more often than not, the government just announces the MSP for a crop and has very limited ability to influence the actual market prices, which is what the farmers get paid. Even in case of crops like rice and wheat, where the government buys a significant amount of the produce (close to one-third of the production, in each case), many farmers get paid a price which is below the MSP. (This is the main point I discuss in the previous piece on this subject).

So, how can we assume that farmers growing other crops will get the MSP? There is clearly no evidence for the same.

- Over the years that the government has bought rice and wheat directly from farmers, the procurement has largely been limited to a few states, primarily Punjab and Haryana. In the case of rice, there are decent procurement operations in a few other states like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha and Chhattisgarh. In the case of wheat, decent procurement happens in Madhya Pradesh.

The point is that the government (and not just the present government) hasn’t been able to build a procurement operation spread decently across the length and breadth of the country, in all these years.

Now, imagine being able to build a procurement operation for all the 22 crops for which the MSP is announced. Clearly, the government doesn’t have the capability for the same.

- Direct buying leads to excess procurement of crops by the government. Take the case of rice and wheat. As of October 1, the total foodgrains that need to be maintained in the central pool as per stocking norms should be 307.70 lakh tonnes. As of October 1, 2018, the total amount of food-grains in stock stood at 542.59 lakh tonnes. This is 76 per cent more than what is required. Now imagine the thousands of crore of government money that is blocked up in this. And the Indian government isn’t exactly floating around with a lot of money, especially in the current financial year, where the goods and services tax (GST) collections have been way lower than the target set at the beginning of the year.

Further, even after the government godowns having so much extra rice and wheat, there is clearly no shortage of foodgrains in the open market. This means that there is a clear overproduction of rice and wheat happening, because the government buys it.

- Now, storing rice and wheat is relatively simple. The same cannot be said about something like pulses. Also, the rice and wheat that the government buys is distributed through the public distribution system through the length and the breadth of the country, in order to meet the needs of food security. What will the government do with the other crops if it starts buying them? Selling it at the wrong time can lead to prices of that particular crop falling.

- By buying a few crops across few parts of the country and not other parts of the country, the government knowingly promotes inequality. Over and above this, the MSP policy followed by assured procurement sends out the wrong economic signals to farmers.

Take the case of Punjab, a semi-arid area growing rice. The state is the third largest rice producing state in India. It barely consumes any rice. At the same time, 92 per cent of the rice produced gets procured by the government. Of the total cropped area in the state, rice has a 36 per cent share. This despite the fact that the semi-arid state guzzles up a lot of water in the process.

As Ashok Gulhati and Gayathri Mohan write in a research paper titled Towards sustainable, productive and profitable agriculture: Case of Rice and Sugarcane: “West Bengal can produce almost 42 kg of rice from one lakh litres (equivalent to 100 cubic metres) of irrigated water while Punjab can produce only 19 kg of rice from the same quantity of water. More precisely, Punjab consumes almost two times more water than West Bengal and almost three times more water than Bihar for producing the same one kg of rice. Bihar tops the ranking with highest productivity of rice per unit of irrigation water consumed (56 kg/ lakh litres).”

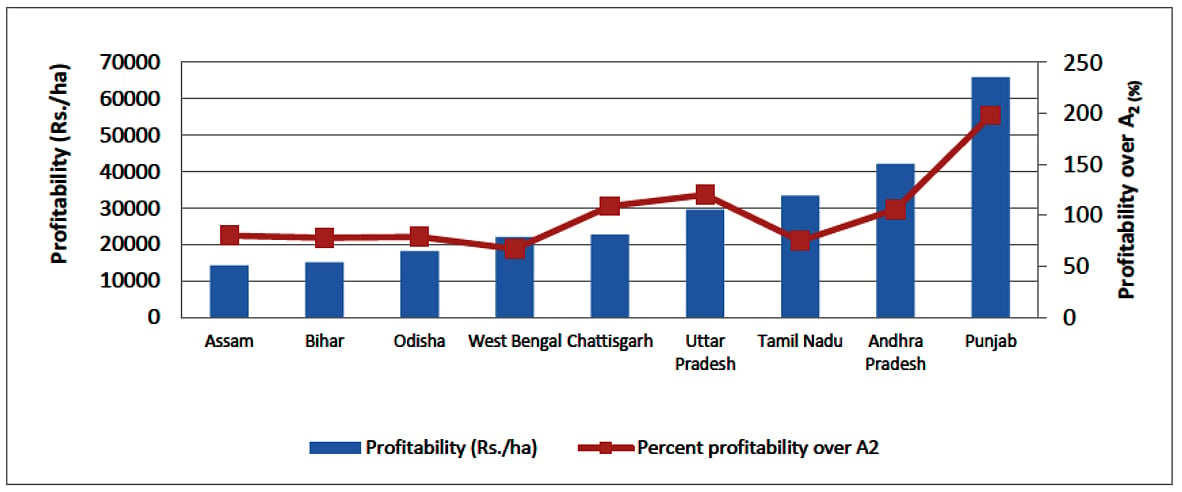

The question is why is Punjab still growing rice? Simply because the FCI has good procurement operations in the state and there is a steady customer in the form of the government in place. The funny thing is that despite hurting the environment in a big way, Punjab continues to grow rice very profitably. As Gulhati and Mohan point out: “Unfortunately, the states like Assam and Bihar with high irrigation water productivity do not have efficient procurement system for rice and hence their farmers often receive paddy prices which are way below the corresponding minimum support prices (MSPs). The net result of such a policy environment is that their profitability remains much lower.”

Take a look at Figure 1, which basically plots what is said in the above paragraph.

Figure 1:

The MSP policy has also played its role in keeping a state like Bihar backward for so long.

- The biggest problem with tSP is the belief that one pan-India policy can solve a problem. Also, the MSP is a solution from an era when India did not produce enough agricultural crops. Those days are behind us. Further, MSP does not do anything for the cause of vegetables and fruits, for which no MSP is declared but are also a part of the agriculture distress.

So what are the solutions to this problem?

- The agriculture distress problem cannot be managed just out of Delhi. Given this, the MSP policy needs to abandoned and every state government should be allowed to run policies which they deem fit.

- 64 per cent of the rural workforce works in agriculture. It produces 39 per cent of the economic output. It is clear that agriculture employs many more people than is economically feasible. Hence, jobs need to be created in other areas to help people get out of agriculture.

- The current APMC based model is clearly not working. It is a model made totally for the intermediaries and does not help the farmer or the end consumer. Under the state APMC Acts, the farmers need to sell their produce at state-owned mandis. And this is where the main problem lies.

As Tanvi Deshpande points out in a report titled State of Agriculture in India: “APMC mandis currently levy a market fee on farmers who wish to sell their produce in the mandis. This makes it expensive for farmers to sell at APMC mandis. In addition, farmers have to arrange for their produce to be transported from their farms to the nearest mandi, which brings in costs such as transport and fuel. In transporting the produce from the farm to the store, several intermediaries are involved. These intermediaries are all paid a certain proportion of the price, as commissions. Thus the market price which the farmer receives for his produce is significantly lower than the price at which his produce is sold to the retailer.”

Also, the right price discovery doesn’t happen at these mandis, which is criminal. How can this be corrected for? As the document titled Price Policy for Rabi Crops—The Marketing Season 2019-2020 points out: “Private sector participation needs to be encouraged and incentivized to create competitive markets for better price discovery … Role of the private sector in agricultural marketing is extremely important and cannot be ignored. Therefore, efforts should be made to attract organized private sector agribusiness companies in agricultural trade through appropriate incentives and reducing legal hurdles by amending APMC Act and Essential Commodities Act (ECA).”

If given an opportunity, big retail chains will surely be interested in sourcing crops directly from farmers. The document Price Policy for Kharif Crops—The Marketing Season 2018-2019 points out: “Enabling mechanism are also required to be put in place for procurement of agricultural commodities directly from farmers’ field and to establish effective linkage between the farm production, the retail chain and food processing industries.” The government cannot achieve this on its own.

- In fact, the document referenced in the previous paragraph has an excellent example of successful private sector participation. As the document points out: “The private sector can play a significant role in enhancing investment in the agriculture sector. In a few cases where corporates are taking innovation to farmers with inputs, wonderful results have been achieved. One such case is the banana revolution in Jalgaon district of Maharashtra where farmers are using tissue-cultured banana saplings supplied by a private tissue culture lab for disease-free banana cultivation and getting much higher yield and better quality fruit… The lab is now expanding the same technology to other states and fruits. If such practices are replicated in foodgrains, India can become a global hub for agricultural production.”

The larger point here is that all the solutions already seem to be there in the documents being produced by a section of the government.

- Ashok Gulati, Tirtha Chatterjee and Siraj Hussain in a research paper titled Supporting Indian Farmers: Price Support or Direct Income/Investment Support?, published in April 2018, summarise the solutions: “Wisdom lies in thinking rationally now, and support farmers through less distortionary policies. It may be through investing heavily in marketing infrastructure, storage and food processing, changing the APMC Act to allow direct buying from farmer producer organizations (FPOs) bypassing the archaic mandi system, or direct income (investment) support (DIS) on per hectare basis, as recently announced by Telangana and Karnataka.”

The MSP policy is basically a huge distortion on the economy and needs to go.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy).