Why the RBI monetary policy has become useless

An expansionary fiscal policy and an easy monetary policy cannot be run parallelly.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been batting for low interest rates for a while now. Between January and now, the repo rate has been cut by 135 basis points to 5.15 per cent. Repo rate is the interest rate at which the RBI lends to banks. One basis point is one-hundredth of a percentage.

The hope was that the repo rate cuts carried out by the RBI will lead to banks cutting interest rates on the loans they give. At lower interest rates, people would borrow and spend, and corporates would borrow and expand, and the economy would recover.

But that doesn’t seem to be happening.

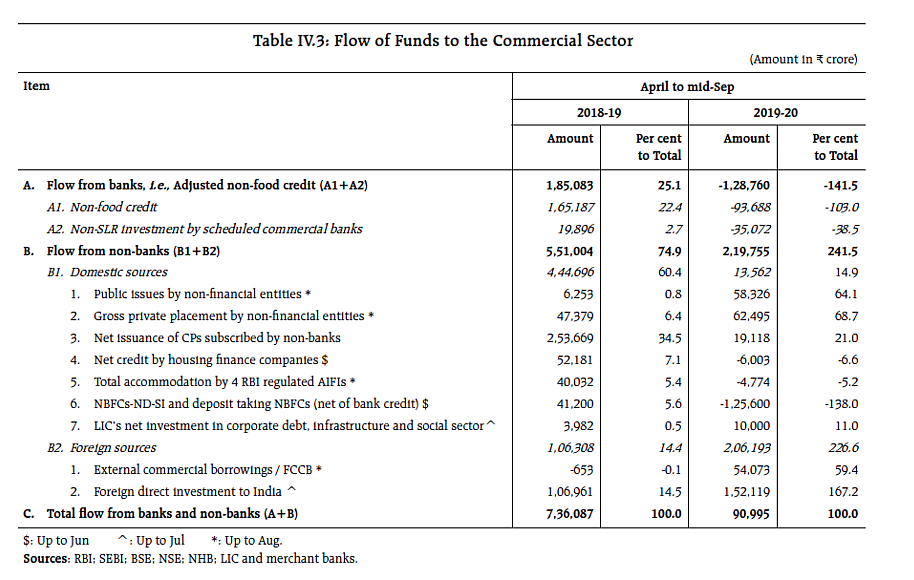

In fact, non-food credit growth during the course of this financial year has simply collapsed. Take a look at the following table. The table has been taken from the RBI Monetary Policy Report released last week.

What does the above table tell us? Look at entry A1 or non-food credit. What is “non-food credit”? Banks give loans to the Food Corporation of India and other state procurement agencies to primarily buy rice and wheat (and recently, pulses and oilseeds as well) directly from farmers. When this lending is subtracted from overall lending of banks, what remains is non-food credit which is divided into four segments: agriculture, industry, services and retail (or what the RBI calls the personal segment).

The non-food credit lending carried out by banks contracted by ₹93,688 crore between April 2019 and mid–September 2019. What does this mean? Basically, on the whole, banks did not give a single rupee of a fresh loan between April and mid–September. The overall loans given by banks contracted by ₹93,688 crore. This despite the RBI cutting the repo rate.

Theoretically, the rate cuts by the RBI should have led to rate cuts by banks (as the media keeps telling us on every occasion that it gets) and should have finally led to higher borrowing. But all that is not happening. There is a difference between how things should have happened in theory and how they’re happening in practice.

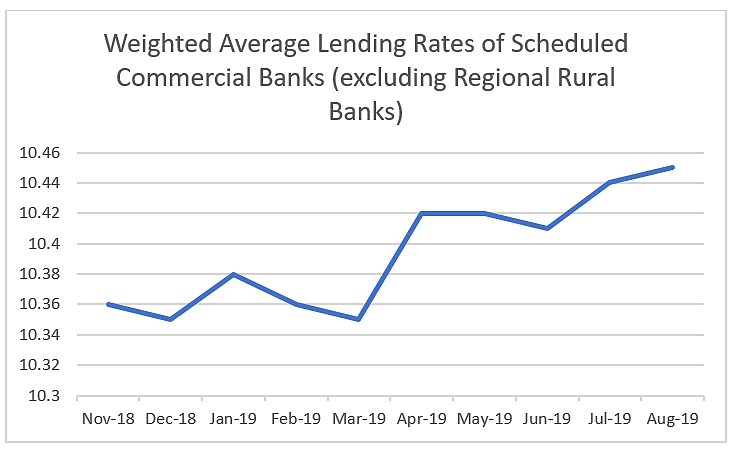

Take a look at Figure 1. It plots the weighted average lending rates of banks between November 2018 and August 2019.

Figure 1. Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy

As can be seen from Figure 1, the interest rates at which banks lend have gone up marginally between January and August, despite the RBI cutting the repo rate. The interest rate went up marginally by seven basis points from 10.38 per cent in January 2019 to 10.45 per cent in August 2019.

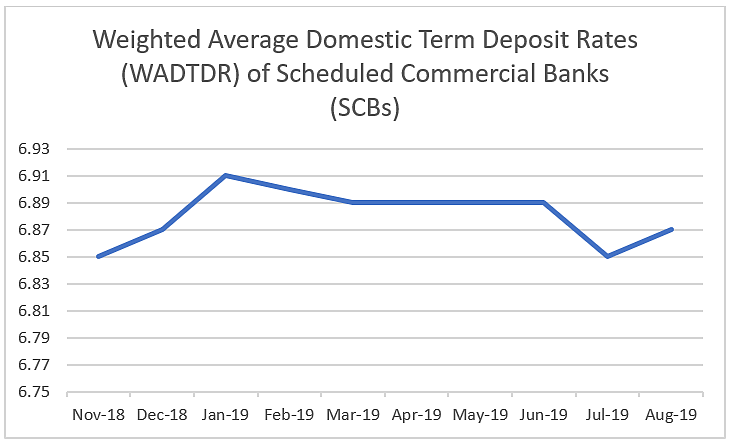

Why has this happened? Take a look at Figure 2. The interest rates at which banks raise term deposits have more or less been constant.

Figure 2. Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy

What does Figure 2 tell us? It tells us that the interest rate at which banks raise their term deposits has more or less been constant since the beginning of the year, varying between 6.85-6.91 per cent.

Hence, despite the RBI repo rate cut, the rate at which banks raise term deposits has barely changed. Banks raise deposits and lend them out. Unless deposit rates fall, there is no way lending rates can fall. It is worth remembering here that deposit rates get locked in at the time a deposit is made.

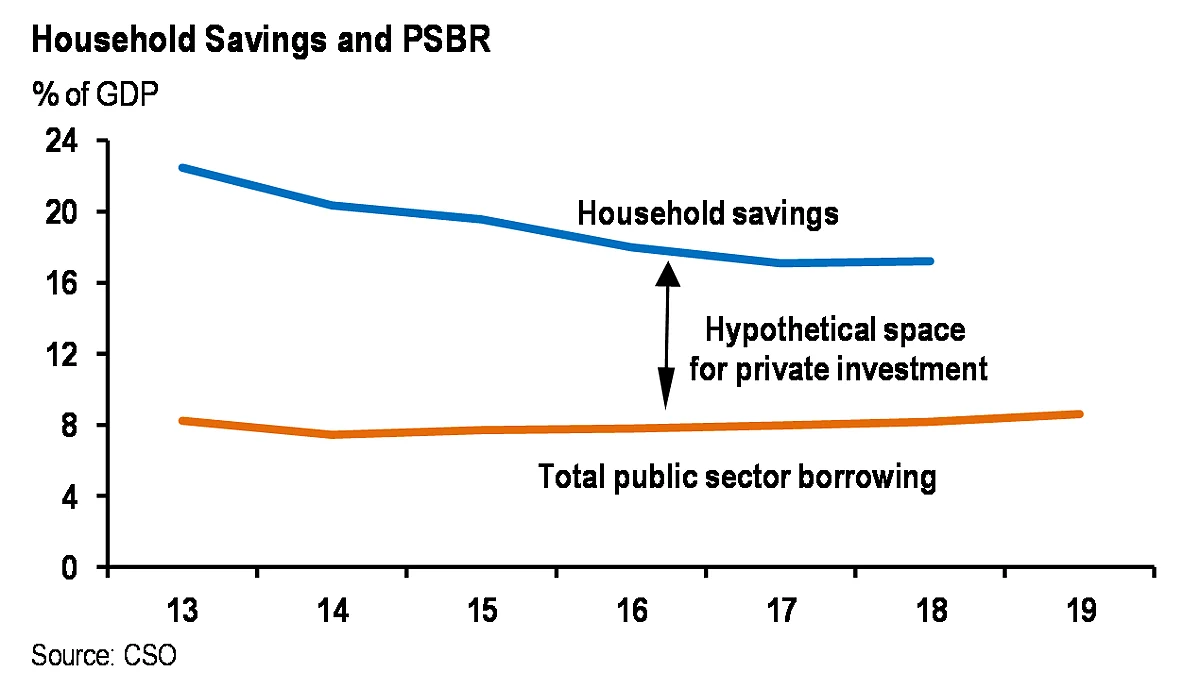

The question is: why have deposit rates not changed? Look at the following chart which plots the public sector borrowing requirement (PSBR) along with the household financial savings.

PSBR is obtained by adding the fiscal deficit of the central government, the combined fiscal deficit of the state governments, off-balance-sheet borrowing of the central government (for example, the borrowing carried by the Food Corporation of India for which the government doesn’t compensate it on time) and borrowing by all central public sector enterprises. This is the actual borrowing carried out by the Indian government and over the years, it’s increased from around 8 per cent of the GDP to around 9 per cent of the GDP. This in an environment where household savings have come down dramatically.

Hence, lesser savings are available but the amount of government borrowing has gone up. This has led to even lesser savings being available for the private sector. This has ensured that interest rates continue to remain high even though much lending isn’t taking place.

This is happening in a situation where the government is not earning enough taxes — at least nowhere near what it expected when the budget for the current financial year was presented. The gross tax revenue collected between April and August has grown by just 4.2 per cent. If the expenditure that the government has budgeted for needs to be met, the gross tax revenues need to increase by 18.3 per cent. Clearly, the growth in taxes collected has slowed down dramatically.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the collection of the goods and services tax (GST), which has collapsed. This is another indicator of slowing consumer demand.

In this scenario, the monetary policy of the RBI or the RBI majorly cutting the repo rate has essentially become useless. An expansionary fiscal policy (with the government having to borrow more and the expectation that it will continue to borrow more) and an easy monetary policy (interest rates going down) cannot be run parallelly.

Also, it is worth remembering that people and corporates borrow when they have confidence in their economic future, which has gone missing in the recent past. The consumer confidence has dropped to a six-year low as per the RBI.

This is Economics 101, as basic as it can get, but corporate and government economists seem to be completing missing this.