No answers, no access, no accountability: Journalists struggle to get information from the government as Covid-19 crisis worsens

Press briefings are shorter and not all journalists can participate, while the Press Information Bureau says they must not get ‘offended’.

Information policing seems to have been one of the hallmarks of the Indian government’s strategy to fight the novel coronavirus crisis. From stonewalling journalists at press briefings to approaching the court to regulate content, recent developments have highlighted its growing eagerness to control news on the ongoing coronavirus emergency.

For some time, journalists are struggling to get data from evasive bureaucrats on the country’s stockpile of equipment, testing kits, and other medical facilities. Now, they’re not even sure they’ll be able to ask those questions any more.

Though cagey, for more than three weeks now, the Indian government’s afternoon press conferences served as an official avenue of communication between journalists and government officials on the unfolding crisis.

The briefings are addressed daily at the National Media Centre in Delhi, led by Lav Agarwal, the joint secretary of the health ministry. Moderated by KS Dhatwalia, the principal director-general of the Press Information Bureau, the briefings have turned into “highlight sessions” by the government — a recitation of daily updates for nearly two-thirds of the time allotted, and fielding just a handful of questions from journalists thereafter.

Since the nationwide lockdown began, given that many journalists can’t physically attend, an arrangement was made where questions could be submitted in a WhatsApp group moderated by the Press Information Bureau. At the briefings, apart from live questions from reporters present, some of the queries from the group would also be taken up.

However, as the disease continues to spread at a faster rate, bottlenecks have come up in the process.

Shorter press briefings

To begin with, the government’s daily press briefings have suddenly become shorter over the last three days. While the briefing on April 1 lasted for less than 14 minutes, the briefing on April 2 was just about 21 minutes. On April 3, it continued for a little more than 14 minutes.

Earlier, according to many of those who attended, the interaction would last for at least 35-40 minutes, sometimes even stretching to an hour. This is clear from clips of prior briefings on the PIB’s YouTube channel. For example, the two briefings before April 1 ran for about 49 minutes and 42 minutes, respectively. Accordingly, reporters would try to get a range of information on the government’s preparedness and strategy to fight the virus.

“There used to be more than 10 questions addressed in a briefing. But now, with less than half the earlier time, the number has naturally dwindled,” said a senior health reporter, on the condition of anonymity. For example, at the April 1 briefing where she was physically present, only three live questions were taken.

On April 2, a total of six questions were entertained from journalists. Interestingly, the officials had already wrapped up after answering the first four questions. As they stood up, a journalist shouted a question from the back. The panellists then sat down again and one of them answered. Senior journalist Shekhar Gupta then managed to squeeze in a question too.

“Mr Dhatwalia, who is the principal director general of the PIB, moderates the conversation,” the reporter explained. “He would read out two or three select questions posted online and the panellists would then answer.”

At the briefings on April 1 and 2, the officials recited daily updates — like numbers of new cases and deaths in the last 24 hours, the Centre's different guidelines to the states, efforts to trace the Tablighi Jamaat attendees — for almost two-thirds of the time. Once they finished, Dhatwalia handpicked a few journalists to field questions. Before others could ask anything further, the briefing ended. It was barely even a press conference.

The briefings usually feature a few regular faces, including a representative each from the health ministry, home ministry and the Indian Council for Medical Research.

“This has been the usual setting for some time now. But earlier, depending on the situation, there were others too. For example, when there were issues concerning air travel, there was a representative from the civil aviation ministry,” the reporter explained.

Selective access

But shorter interactions with the press is only one of the problems.

Journalists covering Covid-19 told Newslaundry the government has become selective about which journalists could ask questions.

On April 1, according to a reporter who is part of the PIB’s WhatsApp group, a message was posted that only reporters from ANI and Doordarshan could attend the briefing. Doordarshan is run by the state, and ANI isn’t exactly known for its independence.

“There was an immediate backlash on the group as several journalists protested it. Given the strong reaction, later, there was another message from a PIB official saying everyone could attend as usual,” the reporter said, on the condition of anonymity.

Despite these assurances, the briefing was pretty much what the first message had implied.

“They took one question each from DD News and ANI, and one more from the media WhatsApp group. Then there was one last question from someone else, I could not figure out who,” the reporter said. “Everything happened in a rush."

However, other journalists were still allowed to attend the April 1 briefing. But this changed on April 2, when only those with accreditation from the PIB were admitted. Among other criteria, this accreditation is given to journalists with more than five years of experience. Also, it is limited to print and electronic media, which leaves out all digital platforms.

Reluctance to share information

A reporter with a leading newspaper said this indicates the government’s growing reluctance to share information.

“Even in the earlier briefings, they would not give us straight answers. For example, if we asked them about the number of certain protective equipment available in the country, they would say it was ‘enough’, or more was being ordered,” the reporter said. “But the figures would not be shared.”

Yet, she emphasised that the briefing was a vital channel of communication, allowing journalists to repeatedly ask important questions about things like safety gear, ventilators and kits.

“This was an effective medium as we could build a collective pressure. When several of us constantly asked the same sets of questions, they could not avoid [answering] beyond a point. They had to answer, even though it took days,” she explained. “That is the advantage of open press briefings. But now, they are cutting down access as well as answers.”

In the April 2 briefing, she said, despite questions from reporters, officials did not reveal the total number of tests done in the last 24 hours.

“If you are not giving out such crucial information, why call us amid this lockdown situation? This is insulting,” said the reporter, who attended the briefing since she has accreditation from the PIB.

Rema Nagarajan of The Times of India agreed. According to her, many state governments are coming up with detailed updates daily. In contrast, the data released by the Centre is a “mess”, she said.

For example, Nagarajan said, despite repeated queries, there’s still no clarity on the companies approved by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation for selling Covid-19 test kits in India.

“They have not informed [us of] the detailed criteria for that, vaguely mentioning only about necessary foreign certification. But is it US FDA or European CE certification or anything else, we do not know,” Nagarajan said. “What is the great secrecy about such important information?”

Several health reporters told Newslaundry that the government’s daily press briefings failed to address many of their queries.

“Be it about the stock of personal protective equipment or the Covid-19 test kits, we had to ask the same question a dozen times,” said a journalist who attended several briefings. “Sometimes, it was like banging your head against a wall.”

Another journalist pointed towards the government’s controversial denial that there is community transmission in India — the third and critical stage of Covid-19. There are multiple instances where a patient’s case looked like a case of community transmission, he said.

“But strangely, the government has not been clear on this. They just insist it should not be classified as community transmission,” the journalist said. “They may have their own metrics to determine it. But then, that should be shared with us.”

One possible reason for this refusal could be the low number of tests conducted by the government to come up with a conclusion, he added. “It’s weird that the government is behaving as if the virus was their fault. Rather than suppressing data, they should ramp up testing and identify all potential cases.”

Lack of accountability

Bureaucrats and scientists have their limitations in answering questions, one of the reporters said, and there are political issues that need to be addressed too.

“Dr Harsh Vardhan, the union health minister, has surprisingly disappeared from the scene,” he said. “Since Tablighi Jamaat made news a few days back, journalists have a number of questions for the government.”

He cited reports of other religious congregations in Punjab and Tamil Nadu taking place around the same time. “So, the question is: why have they not been listed as hotspots like Nizamuddin? Is there any political factor behind [it]? But you cannot ask all this to Harsh Vardhan or any other minister since none of them is facing the media.”

In contrast, the coronavirus outbreak has compelled many heads of state in other countries to regularly engage with the media. Even Donald Trump, known for his frequent run-ins with journalists, has made an exception in this hour of crisis. The prime ministers of Canada and the UK similarly interact with journalists from time to time.

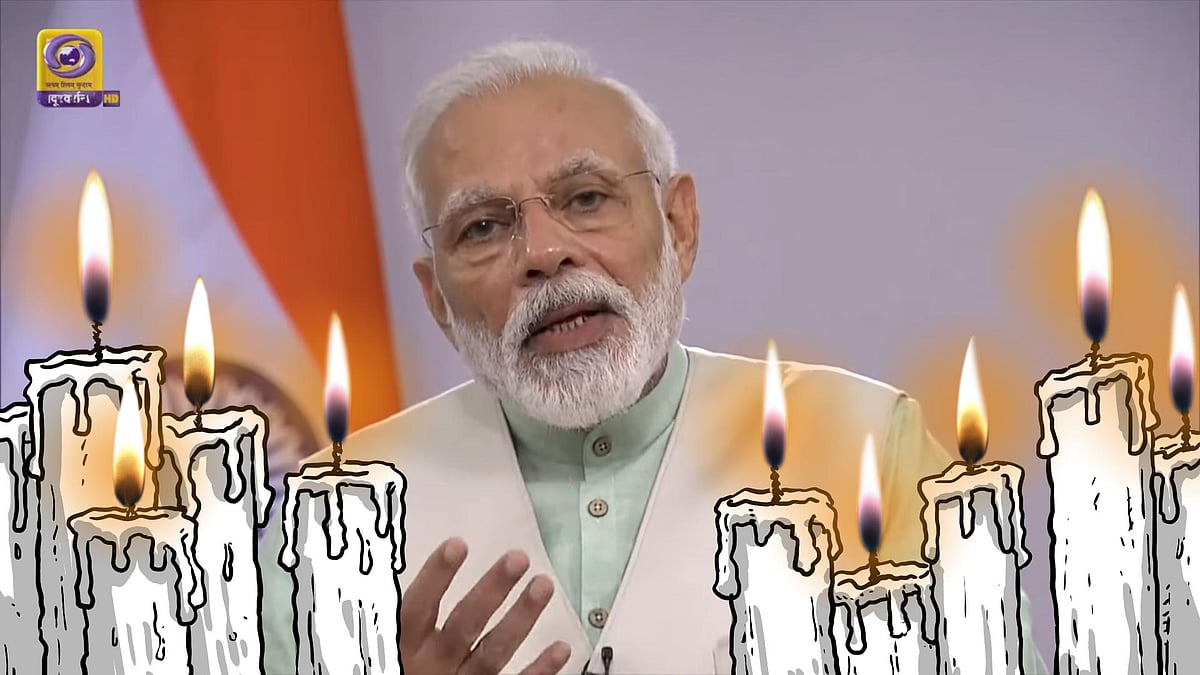

Narendra Modi, on the other hand, has only made public appeals so far. First, he urged people to clap and clang utensils. In his latest video appeal, he urged citizens to light lamps. This, he said, would boost the morale of all the professionals fighting the outbreak from the frontlines.

Many of Modi’s Cabinet colleagues have not even done as much. Home minister Amit Shah, like Dr Harsh Vardhan, is missing from public view. And when ministers do surface, it’s for pointless photo ops like watching television shows.

Journalists turn to state governments

The reality is grim, however. With nearly 3,000 cases and 60-plus deaths, the disaster is accelerating in India. Simultaneously information is being further suppressed. If the situation stays this way, several reporters told Newslaundry they will have to rely on the data put out by state governments. As before, they will have to continue to rely on scientists and doctors for expert inputs.

“States like Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Delhi are doing a great job in providing daily updates,” one of the journalists said. “Also, most of the recent cases have come from there. So, when the Centre is adopting a guarded approach, we will have to turn to these states for regular information.”

Unlike with the central government, political accountability is not missing in some states. Respective chief ministers and health ministers constantly engage with the press — directly and on social media — to update and assure the public. Reporters are apprised of the situation with detailed health bulletins every evening. There’s also been prompt response in erecting medical facilities within short durations. In a way, states have actually shown the way in battling the disease.

Given this, Rema Nagarajan said it was ironic for the central government to approach the Supreme Court to regulate coronavirus-related content in the media. “If they are so worried about media peddling misinformation, they should first come up with sufficient information,” she shot back.

Nagarajan was referring to the Centre’s appeal in the Supreme Court for the media to get the government’s prior approval before publishing anything. The appeal was made when the apex court was hearing a petition about the recent exodus of migrants due to the country-wide lockdown. Misinformation and fake news were deemed as a factor responsible for the mass migrations.

On March 31, the apex court, without completely acceding to the government’s request, directed media outlets to publish the government’s official version of developments pertaining to the coronavirus outbreak.

Journalists haven’t been happy with the order. On April 2, the Editors Guild of India issued a statement, saying: “Blaming the media at this juncture can only undermine the current work done by it under trying circumstances. Such charges can also obstruct in the process of dissemination of news during an unprecedented crisis facing the country.”

Given the current scenario, Nagarajan said the government should come up with a coordinated mechanism to release information in one place.

“Now they have restricted access to many journalists in the daily briefings. They also cherry-pick questions from the WhatsApp group. It is not important where the information comes from. Be it the ICMR or the health ministry, but there should be regularity and uniformity in the government data,” she said.

Nagarajan suggested that the government set up a platform for journalists to pose their questions directly, appointing dedicated officers for that purpose.

In fact, the government’s recent reserved responses prompted many journalists to come up with a common questionnaire. Scroll published 10 questions posed by the collective of health reporters with the sub-heading, “Basic information remains shrouded in secrecy”. The document highlighted some important questions before the government which have gone unanswered in the briefings. These included queries about the country’s Covid-19 testing regime, safety gear and insurance for healthcare workers fighting the disease, and preparedness at the community level.

‘You cannot get offended’: PIB

Kuldeep Singh Dhatwalia, director general of the PIB, told Newslaundry there’s always a time constraint in press interactions.

“We can’t obviously take all of them [the questions]. So, we try to club some questions and take some the next day,” he said.

Why are only PIB-accredited journalists being allowed to participate in the briefings? Dhatwalia said it was not a new development.

“By rule, only those with the accreditation are technically allowed to attend PIB press briefings. But considering the current situation, we took a positive approach and allowed others to attend and listen,” he said. “Some important questions were also taken from them.”

But this could not continue longer, he added, as many of them did not “reciprocate” the gesture. “When you are allowed to participate through a special arrangement, you cannot get offended for not getting to ask a question. Without accreditation, you are not entitled. Yet, people complained. So, we had to stop it finally and stick to the rule again.”

A reporter who attended many of the briefings agreed with the PIB chief. Even earlier, she said, only accredited journalists were technically permitted to attend.

“But there was an understanding between the organisers and us which also allowed non-accredited journalists to actively participate. This facilitated broader conversations. I don’t understand why that has been changed suddenly,” she said.

Dhatwalia, however, said there was no reason for journalists reporting on Covid-19 to worry. Like before, their questions would continue to be taken through WhatsApp and email, he assured. “We are also trying to have a portal where journalists can straightaway post their questions online. It will be up very soon” he said.

As the crisis continues, it remains to be seen how the government engages with the media and disseminates information. When asked what might be the consequence of curbing communication with journalists, a reporter, on the condition of anonymity, said it can lead to a panicky situation.

“It’s not about us. The government has a responsibility towards the people to provide up-to-date information. In an emergency situation like this, the information outflow should be better actually,” said the reporter. With the situation worsening, in the absence of adequate information, various rumours could circulate making people more tense, she added.

As states show the way to fight COVID-19, federalism in India gets a much-needed boost

As states show the way to fight COVID-19, federalism in India gets a much-needed boost

Candle in the corona storm: Brace yourself for some TV news excitement

Candle in the corona storm: Brace yourself for some TV news excitement