Temple locked, business lost: How Shirdi’s economy collapsed due to the Covid pandemic

Most businesses in the Maharashtra town are dependent on visitors to the famous Saibaba temple, from flower shops to hotels to puja stores.

In July last year, the governing trust of the renowned Saibaba temple in Maharashtra’s Shirdi received donations of about Rs 5 crore during the three-day Guru Purnima festival. Around six lakh people came to Shirdi for the festival, and the temple town did business of nearly Rs 40 crore.

This wasn’t unusual for Shirdi. Home to a famous temple of the 19th century saint Saibaba, the town’s 13 sq km area is often packed with devotees, far exceeding its resident population of 35,000. After the coronavirus pandemic hit India, however, business came to a standstill.

Today, this once booming town is deserted. With the temple locked, the economy dependent on it – restaurants, flower shops, stores selling puja paraphernalia, bus operators, and others – is in shambles. Before the lockdown, Shirdi did an average daily business of Rs 10 crore a day, and the temple trust earned over Rs 600 crore per year.

Now, the average daily business is a few lakh rupees, if that.

Arun Dongre, the chief executive officer of the Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust, which manages the temple, told Newslaundry that donations have fallen, and businesses dependent on the temple are struggling.

“People usually throng Shirdi between March and July. The two biggest festivals, Guru Purnima and Ramnavami, take place during these months,” Dongre said. “In a single day, the footfall during these festivals is in lakhs. In these four months, the trust generally earns up to Rs 200 crore, but this year, we lost those earnings.”

He added: “We have written to the government to open the temple with standard operating procedures. I don’t think the temple will remain closed for a long time. I think it will start in a month or two.”

Dongre further said the dip in the trust’s revenues won’t affect the retention or payment of salaries to its employees.

The Venkateswara temple in Andhra Pradesh’s Tirupati reopened for devotees in June. Since then, 160 employees have tested positive for Covid-19. However, the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, which governs the temple, has controversially announced that the temple will remain open.

Sachin Tambe, a former trustee of the Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust, said the economy of Shirdi and nearby villages is in “distress”, since every business in the area is dependent on the temple and its visitors. Before the lockdown, he explained, the average collection of donations per day was Rs 1 crore, with almost equivalent expenses.

“Last year, the trust’s annual income was Rs 679 crore and expenses were Rs 609 crore. Rs 410 crore was spent on the salaries of over 6,000 employees,” Tambe said. “Presently, the trust has stopped receiving donations but the expenses are the same. Our daily expenses are still Rs 1 crore per day, but donations per day are only Rs 80,000-1 lakh.”

He added that the trust received donations of Rs 80-90 lakh this year during the Guru Purnima festival, as opposed to its usual donations of Rs 4-5 crore during previous years.

As a result, the trust is currently running on reserve money. It has a reserve fixed deposit of Rs 2,300 crore, of which Rs 400 crore is earmarked for development projects and Rs 500 crore for the Nilwande dam. Employee salaries are now being paid from matured fixed deposits.

“If people do not start coming to Shirdi, it will totally devastate the personal economy of people here,” Tambe said. “People have loans, the hotel industry has been badly affected. Shirdi’s basic economy is in dire straits.”

Hotel industry in crisis

There are around 1,500 big and small hotels in Shirdi, said Abhay Shedke, a renowned hotelier in Shirdi and a member of the town’s hotel association. Shedke himself runs a hotel and two restaurants earning a total monthly turnover of Rs 1.5 crore. This was before the Covid outbreak: his earnings now stand at zero.

“In 2018, around 3.5 crore devotees visited Shirdi as per official data. The hotel industry here is totally dependent on devotees,” he said. “Now, the footfall has come down to zero. This has directly affected the hotel industry in the town.”

Devotees visiting Shirdi usually have a decent spending capacity, he added, since a majority of them are from middle class and upper middle class backgrounds. According to him, on a busy day, a small roadside hotel would earn Rs 40,000-50,000 a day. Larger restaurants would earn Rs 1-1.5 lakh, and even tea shops would make about Rs 10,000 daily. One of his restaurants, which has 20 tables, would earn Rs 1 lakh a day and the other about Rs 5 lakh a day.

Ninety percent of Shirdi’s hotel industry is run by locals, Shedke said. Most hotels and restaurants pay rent for their properties, and the amount varies on the basis of their proximity to the temple.

“The monthly rent of a restaurant near the temple can go up to Rs 8 lakh a month, while a restaurant further away pays about Rs 1 lakh as rent,” he explained. “Landlords also have to be paid a fixed amount on a daily basis, ranging from Rs 20,000 to Rs 50,000. But for the last four months, people have not paid rent. Even the landlords are not asking for it. But they are facing problems too as they are totally dependent on rent to take care of their own expenses.”

Before the pandemic, Shedke employed 180 people across his hotel and restaurants. Now, he only employs 40. “There is zero earnings for the last four months but I still pay Rs 2 lakh a month as maintenance costs for my properties,” he pointed out.

Earlier this month, the Maharashtra government passed an order allowing hotels to operate with 33 percent occupancy and restricted entry. But Shedke does not see that helping the hostel industry in Shirdi.

“Until the temple opens, visitors will not come. And everything will remain as it is,” he said. “Even if the temple opens as per some standard operating procedure, only 4,000-5,000 devotees will visit Shirdi as opposed to the average footfall of 40,000-45,000. In short, Shirdi will not get its booming economy back until a vaccine is developed for Covid-19.”

Struggling with low earnings, no savings

Before the lockdown, Ravindra Gondkar, 43, earned about Rs 40,000 a day, of which he would pay Rs 24,000 to his 300-400 employees. Now, he earns barely Rs 500 a day.

For the last 22 years, Gondkar has run flower and prasad shops in Shirdi. “I would buy flowers from farmers and make garlands to sell. I would also deal in prasad and shawls for temple offerings,” he said. “Whatever I earned, I would reinvest in my business. Now, I’m surviving on my savings but I don’t know how long they will last.”

Gondkar owns two acres of land, and has spent the lockdown farming and growing vegetables. “There is no sense in opening my shops because devotees are not coming to Shirdi,” he said. “These days, I sell vegetables from my own farm and earn Rs 500 per day.” He manages to earn about Rs 15,000 a month but worries about the boys who worked with him on commission. “They are in really bad shape.”

One of Gondkar’s shops, a 110 sq ft space, carries a rent of Rs 40,000. He hasn’t paid it for four months. “I have not spoken to the owner about it,” he admitted, “but I believe everyone in Shirdi understands that no one has any earnings. That’s why no one is asking for rent. Everything is uncertain now. We don’t know whether Shirdi will be able to get back on track or not.”

Another industry hard hit in Shirdi is the “polishywalas”, a local term for commission agents. These agents take devotees to hotels, flower shops, and travel agents, and receive a commission in return. Most of the town’s polishywalas are youths from poor economic backgrounds. A polishywala can earn Rs 3,000-5,000 for three hours’ work on a busy day, sometimes even more.

Vicky Bhalerao, 27, told Newslaundry that he had a good life as a polishywala until the lockdown. He would buy branded clothes from malls in Nashik and Ahmednagar, and visit Goa with friends. The present scenario has left him helpless and unsure of whether he can even afford two meals a day.

Bhalerao’s worklife in Shirdi began when he was 14, selling calendar photos of Saibaba. “I used to leave my house at 9 am and return at noon,” he said. “I would carry 100 packs of photos and sell each pack for Rs 10. In three hours, I would earn Rs 1,000.”

Two years later, Bhalerao graduated from calendar photos to Saibaba idols, earning Rs 1,000-1,500 for three hours of sales. After a couple of years, he moved on to selling flowers: buying 100 flowers for Rs 50-60 and selling a bunch of two or three for Rs 10. He would sell about 500 flowers in three or four hours, and could earn up to Rs 4,000 on busy days. During the Palkhi festival, he would earn Rs 5,000 in a few hours.

In 2016, Bhalerao began working as a polishywala, sometimes earning Rs 10,000 a day.

“The minimum earning was Rs 1,000-1,500 a day, sometimes Rs 3,000-5,000 on busy days,” he said. “But I would spend the whole sum by night. I never thought of saving because I thought I could easily make money the next day. I now repent this because I have no money. Whatever I had got over in two months.”

Bhalerao is now trying to earn a living by selling khari, a tea snack, which makes him Rs 100-150 a day. “But people don’t buy khari on a daily basis, so I make money only two or three times a week,” he said.

When Bhalerao met this correspondent, he had only Rs 20 in total. “My mother gave me Rs 50 in the morning,” he explained. “I bought cooking oil for Rs 30. Rs 20 is left.”

But Bhalerao is hopeful: he will soon start working as a daily wager on a construction site, earning Rs 350 a day. Out of the 5,000-odd polishywalas in Shirdi, an estimated 70 percent of them have now left the town to work as construction labourers in Ahmednagar and Pune.

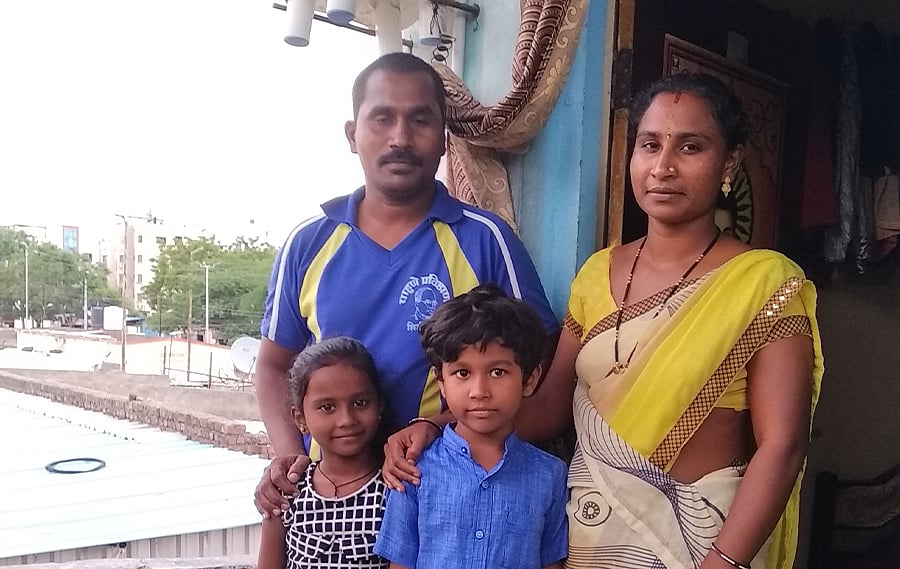

Newslaundry also spoke to Nitin Kadam, 35, who works as a waiter in a restaurant in Shirdi. Before the lockdown, Kadam earned Rs 6,000 per month with daily tips of Rs 500-800. Life was good, he said. “I got my kids admitted to a good English medium school. I bought a 40-inch television set, though I’m now unable to pay the monthly installments of Rs 2,800. Everything is uncertain now.”

With business in Shirdi coming to a halt, Kadam was forced to look for work as a daily labourer to support his wife, Preeti, and two young children. “It’s not easy to get work. I earn Rs 250-300 a day for digging, cleaning, whatever work I can find,” he said.

Preeti, 32, said the family now eats only once a day. “We have not had any oil or sugar for the last two days,” she said. “We don’t know how things will unfold.”

***

Independent media is on the frontlines of the coronavirus crisis in India, as elsewhere, telling stories that need to be told and asking questions that need answers. Support independent journalists by paying to keep news free. Subscribe to Newslaundry today.

‘Scary scenario’: Coronavirus is breaking the back of India’s restaurant industry

‘Scary scenario’: Coronavirus is breaking the back of India’s restaurant industry