‘You cannot unsee us’: Driving with farmers during the tractor rally

A group of farmers heading from Singhu to Delhi gave Newslaundry’s crew a lift. Here’s how their day unfolded.

A young farmer wearing a yellow shirt climbed a barricade placed by the Delhi police on the road leading from Singhu to Delhi. He waved as farmers passed by on their tractors, heading to the national capital. The farmers waved back, yelling the Sikh religious slogan, “Jo bole so nihaal.”

“We don’t trust the government,” said Jaikaran Singh, a farmer who stood by. He tossed flowers at the tractors as they passed him. “We trust the country.”

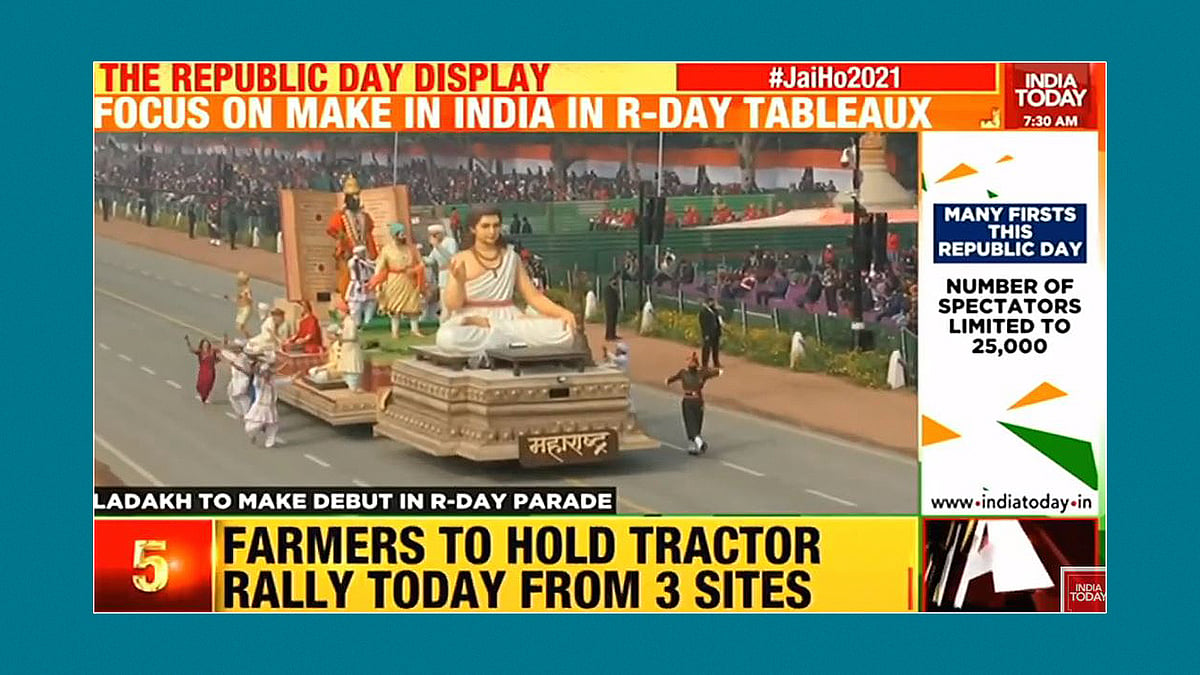

Yesterday was Republic Day, a key moment for the farmers who had been protesting the government’s new farm laws at the borders of Delhi since November. Blocked by the government from entering the capital, they had planned a tractor rally on January 26 to mark their march into Delhi. The rally was scheduled to begin at 12 pm, once the official Republic Day parade at Rajpath ended.

However, by 8 am, the farmers at Singhu had broken through the police barricades and began their march. It was the first time in two months that they drove their tractors along these roads.

Within an hour, the news began pouring in on social media that the farmers from all three of Delhi’s borders – Singhu, Tikri and Gazipur – had deviated from the route assigned to them by the police, and were forcing their ways into Delhi. The police teargassed and lathi-charged the protesters. By 2 pm, the farmers had entered Red Fort and unfurled the Nishan Sahib, the Sikh religious flag.

News channels labelled the rally as “violent” and “chaotic”, even as a form of “anarchy”. At least one farmer died.

However, the scene at Singhu was peaceful. When asked about the violence, a policeman on duty was clueless. “No, as you can see, it is peaceful here and the farmers are following the right route,” he said. “But then this protest is so large. How can one know what happens in another corner?”

The farmers at Singhu told Newslaundry that they were unaware of other protesters deviating from the assigned route. “We’re just following the procession,” one of them said. “I don’t know if anyone is forcing their way to Delhi.”

Designated routes are a ‘joke’

More than 16 km from Singhu border, at Sanjay Gandhi Transport Nagar, the police began teargassing the farmers. It was about 11 am and the farmers had been expected to move down GT Karnal road towards Bawana road and back to Singhu. Instead, they forced their way ahead towards Kashmere Gate ISBT. This led to a brief clash between the farmers and security personnel; soon after, the police stepped back and the farmers began moving towards central Delhi.

By noon, the situation had calmed down. Rapid Action Force personnel guarded one side of the road near Nangloi bridge in Sanjay Gandhi Transport Nagar. The protesters had climbed onto the RAF vehicles and were perched on the top, while the Delhi police stood by. The mood was tense as elderly farmers reiterated that it was important to remain peaceful.

A Delhi police jeep stood on the side of the road, its windshield and windows smashed. Some of the younger farmers gathered in front of it, taking selfies.

“Do not do that. That’s disrespectful,” one of the older farmers chided them. “Somebody got hurt, somebody’s property was damaged. Why are you all celebrating it? We have to maintain peace and respect."

Harshdeep Singh, a farmer from Delhi, told Newslaundry that he was in charge of organising langars along the route of the tractor rally. He was trying to decide whether he should organise the langars along the designated route or towards Delhi.

“No one can protest with a hungry stomach,” he said, laughing.

Harshdeep said the idea of “designated routes” was nothing but a “joke” because the route merely went around the outer peripheral area of the capital city. For the last two months, farmers have been waiting at the borders of Delhi hoping to be heard by the people and the government. Yesterday, many like Harshdeep felt that if they took the designated route, they would once again not be heard or seen as they would remain on the outskirts of Delhi.

“Everything that the government claims to be doing for us is a joke,” he said. “Remember when they gave us the Nirankari grounds to protest when we first arrived? That was hardly 10 km away from our protest. That was also a joke.”

By then, Deependra Pathak, the special commissioner of police (intelligence), had arrived at Nangloi bridge. Pathak intended to try and engage with farmer leaders who were expected to pass through the area. “I want to request them to take the scheduled route,” he said.

But the farmers refused to take Bawana road, which was their designated route and pressed onwards to central Delhi. “Lal Qila ja rahe, Lal Qila,” shouted some of the protesters on the bridge. We’re going to the Red Fort.

Meanwhile, farmers at Tikri and Ghazipur had also broken the barricades and were making their way to central Delhi.

The value of one’s ‘word’

The farmers heading from Singhu to Delhi gave Newslaundry’s crew a lift in a car. Five of us were crammed inside. It was clear that we weren’t taking the designated route, but nobody seemed sure where the procession was headed.

“Aren’t you supposed to follow the designated route?” I asked Babu Pander, a farmer and real estate agent from Barnal who sat with us in the vehicle. He retorted, “Why? Tell me why I should not go to Delhi. Does Delhi belong only to Modi?”

“But wasn’t it agreed that you would follow one particular route?” I said. “Aren’t you going back on your word?”

“Do you know how big this protest is?” Pander asked. “Do you know how many people are here? Why do you think women, children, and old people are sitting on the roads in Delhi in this dead cold winter? It’s because the government failed us, repeatedly. What is the value of the ‘word’ anymore? Who should we trust?”

Pander couldn’t sit still as we drove along; he was happy, joyous, celebrating, like every other farmer we saw. Every time the procession halted, he would jump out, chat with other farmers, distribute water, and take selfies.

“Take, take this ladoo,” he said, pressing not one but two ladoos into my hands. “Eat. We are celebrating.”

What are they celebrating though? Eleven rounds of talks between the government and the farmers have failed. The government offered to suspend the controversial farm laws but not repeal them – which is what the farmers are demanding.

“We are celebrating entering Delhi,” Pander replied. “This is a small victory. It took us six months to be even seen and now, you cannot unsee us. We are here. You have to hear us.”

Even though the mainstream media began covering the protests only in November when the farmers arrived at Delhi’s borders, for many like Pander, the protest began six months ago. In Punjab, the protests had erupted in June, when the laws were first brought in as ordinances.

“I was part of the ‘rail roko’ protest as well,” Pander said. “Every single shop in Punjab shut down, every road was blocked, every person was out on the streets.”

“We were everywhere except on national TV news,” joked Gurkaran Singh, a farmer in the front seat of the car.

To Red Fort or not to Red Fort

As we drove, Pander continuously checked Facebook for news updates. By that time, farmers from Ghazipur and Tikri had reached Red Fort and had hoisted the Nishan Sahib on one of its domes.

This excited everyone in the car. “Now, will people say this is the Khalistan flag?” Pander said.

Pander was joking but this is precisely what happened. Social media began speculating whether the Khalistan flag had been unfurled and if the Indian flag had been defaced. Neither of this was true. The Indian flag continued to fly high and the Sikhs had hoisted their traditional, triangular, saffron flag one level below.

At around 3 pm, we crossed Kashmere Gate where most of the farmers travelling from Singhu took a U-turn and began heading back to the original protest site. “It’s over at Lal Qila,” a farmer said, peering in through our car window. “Everyone is going back now.”

Pander was still scrolling through Facebook, trying to find an official press note from the farmer leaders. He found a video of Balbir Singh Rajewal, president of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (Rajewal) on the Kisan Ekta Morcha page. In the video, Rajewal explained that everything had remained peaceful and thanked the farmers for their support. He went on to urge fellow farmers to “maintain discipline”.

In the car, Pander and Gurkaran began debating whether they should go see the Red Fort or head back.

“We should see it at least once, right? What a historic moment” Pander exclaimed.

“But what if the farm leaders want us to return?” Gurkaran argued. “Maybe they don’t want us to go there.”

Eventually, curiosity got the better of them and we headed to Red Fort. It was around 4.30 pm by the time we reached and the violent confrontation between the police and protesters had subsided. The situation was still chaotic, albeit under control. Both the Sikh flag and the Indian flag were flying high. Groups of farmers were wandering around the fort, eating snacks and taking selfies. The Delhi police stood by, resting and waiting.

Finally, most of the farmers packed up and began their journeys back to their respective protest sites. Their next plan is to walk to Parliament House in Delhi on February 1 when the annual budget is presented.

“We will come back to Delhi soon, this time on foot,” Pander promised.

Photos by Nidhi Suresh and Aditya Varier

Republic Day parade vs tractor rally: What TV news channels showed and ignored

Republic Day parade vs tractor rally: What TV news channels showed and ignored