‘We want to live, not just survive’: Mising tribe protesters have faced decades of broken promises

They were promised rehabilitation by the government after they were relocated in 1950 following an earthquake. They’re still waiting.

For 40 days, nearly 2,000 men, women and children have camped outside the office of the district commissioner in Assam’s Tinsukia. Located some 2,000-odd km from the farmer protests at Delhi’s borders, these members of the Mising tribe from the villages of Dodhia and Laika have been asking the government to relocate them and give them permanent homes.

This protest isn’t new. It’s been going on for 70 years.

After the 1950 earthquake in Assam destroyed dozens of villages, affected families were relocated from Dodhia and Laika to the Dibru reserve forest. In 1986, however, the reserve became the Dibru-Saikhowa wildlife sanctuary, and was then upgraded to a national park in 1999.

With the upgradation – which happened without consultation with the villagers – came a new set of rules; for instance, “human activity” is, by law, not permitted in national parks. As a result, the villages lost access to government facilities and welfare schemes. There are no hospitals and only one ramshackle government school for Classes 1 to 8. Thanks to floods and erosion, the land is no longer habitable or arable.

Since 1999, the residents of Laika and Dodhia have been promised resettlement. And so, the villagers – around 12,000 of them – wait, and protest, and wait some more. Their demand is simple: to be immediately relocated out of Dodhia and Laika.

The protest that began on December 21 is yet another chapter in this struggle.

Yesterday, local news reports claimed the protest had been suspended, following two rounds of discussions with a sub-committee headed by state revenue minister Jogen Mohan. Laika residents had agreed to move to Paharpur and Namphai, the reports said, while the relocation of Dodhia would “take some more time”.

However, this is not true; it’s yet another example of the pattern of misreportage that has surrounded the Mising protests from the start. Members of the protest told Newslaundry that the protest will continue until the rehabilitation begins.

“Promises were made in the past years but they remained unfulfilled,” said Prasanna Narah, a member of the Takam Mising Porin Kebang, a Mising students’ union. “So, we will continue our protest till the day they actually begin to rehabilitate us. Right now, they have just said it verbally. Nothing concrete has been done.”

In July 2017, Prasanna pointed out, the government had pledged that the people would be rehabilitated within eight months. This never happened.

“In the following years, there were several talks with the chief minister, ministers, and deputy commissioner,” he said. “There was a decision taken for the people of Dodhia and Laika to be rehabilitated inside the Digboi divisional forest in an area called Mamorani, and 320 hectares was notified for us. But the people living nearby opposed it, saying it would make living conditions difficult for them. So, we patiently agreed. We did not want to burden them with our presence.”

What led to the December protest?

In August last year, 470 hectares was notified inside the Digboi forest, five km from Mamorani. A proposal was drawn by the Tinsukia district commissioner and the Digboi divisional forest officer and sent to the Dispur secretary’s office. “There were talks again and we were hopeful that something would come out of it,” Prasanna said.

Nothing came out of it, though.

On December 3, the office of the principal chief conservator of forests summoned a handful of Mising elders and said the rehabilitation would require the cutting down of 8,000 trees – even though this had never been brought up during the talks. So, the land would no longer be given to them.

On December 21, Prasanna said, the residents decided to approach district commissioner Diganta Saikia with their demands for immediate rehabilitation.

“He said he would forward our memorandum to the chief minister but he wouldn’t give us a date,” Prasanna said. “We asked if it could be done in a week but they did not agree. That was the day we decided that we would not go back until they rehabilitated us.”

So, about 2,000 villagers crossed the Dibru river by boat to the Guijan ghat in Tinsukia. They walked for three hours to an open area behind the district commissioner’s office, through a narrow road and a village. This large expanse of government land became their protest site.

The space is dotted with tarpaulin tents. Each tent has its own cooking area. The villagers eat a meal together at 9.30 am every morning. Then, from 10 am to 5 pm, they sit together in what is now their main assembly area, where various leaders of the protest make speeches. At night, they brave temperatures that dip as low as 5° Celsius, with only a single blanket each to protect them.

The Takam Mising Porin Kebang arranges food for the protesters, which they cook in their respective tents, along with occasional rations from the government. The district administration has organised an ambulance to visit the site for three hours a day to handle medical issues.

Since the protest began on December 21, three protesters have died. Kushmita Morang, 20, died after an illness following a miscarriage. Reboti Pao, 52, died of pneumonia. Bolen Dang, 70, died of health complications attributed to the severe cold.

Newslaundry visited the protest site on January 6.

Jita Morang, a resident of Dodhia in her late 40s, lay on a sheet, dry hay separating her from the cold earth. Her face was flushed with a fever. She said her chest and body ached and she had a cough.

“It’s not Covid,” she said, her voice a strained whisper as she tried to convince this reporter, or perhaps herself. “I don’t trust the government doctor here, or government doctors in general. There are no medical facilities in our village so we always had to travel five hours to a private hospital if we needed medical attention. Nobody from the government even came for Covid testing to our village.”

Bina Kuli, 35, showed me around the protest site. A mother of two, she took special care in distinguishing between Dodhia tents and Laika tents. It was important, she said, to know that the two identities are not interchangeable.

“I can understand you in your language but you cannot understand me in mine,” she said. “Mising [the language of the tribe] is not taught to our children in schools either. There is an immediate threat to our culture and traditional way of life because of where we are being forced to survive. We need the government to take action.”

No matter how much she explains it, Bina said, it’s impossible to convey the perils they face. “There is no land and no cows,” she said. “Everything has been washed away. All that remains is sand and us. You won’t believe it till you see it.”

Forest dwellers without a forest

Dodhia is an arduous three-hour boat ride from Guijan ghat in Tinsukia. The motorboat’s obnoxious roar is at odds with the serene outskirts of the national park and the stormy grey waters of the Dibru river.

The land is fragmented, the river disintegrating the small stretch of land along which the houses are built. The nearest hospital is five hours away.

Renuboti Kusari, 52, a resident from Dodhia currently at the protest site, said, “We have to hire a boat, which costs Rs 2,000, to take us across, and then a car on the other side of the river...When my sister-in-law was pregnant, she gave birth on the way to the hospital. That happens a lot.”

Given the poor condition of Dodhia’s sole government school, children from Laika and Dodhia are either sent to Dibrugarh or Tinsukia for their schooling. If the families cannot afford it, the children stay home. “People often have to make the difficult decision of either sending their children to school or rebuilding their homes,” Renuboti said. “What kind of choice is that?”

In Dodhia, Newslaundry met Ramakanto Taye, 70. Ramakanto moved here in 1955 after his home and land in Sarisuti village, barely a few kilometres away, was destroyed in floods. He offered this reporter Patanjali biscuits and tea, and apologised for not offering milk with the tea.

“I am left with only one cow now who lost her calf due to starvation, so she cannot produce any milk,” he said. “Earlier, agriculture and cattle thrived on this land. Now, there’s only us people left to survive. Everything else is dead. Nothing can survive on this land. We are forest dwellers but this is not a forest anymore.”

The main occupation in Dodhia was once agriculture. But now, there’s no land to cultivate.

When asked about his land, Ramakanto pointed towards the river. “It’s taken it all. There is nothing left to show. Our way of life is dying, just like this land.”

Once upon a time, Ramakanto said, the area teemed with wildlife and the villagers had access to government amenities. “There used to be elephants, deer and many other animals here,” he said. “But now, the water’s edge has creeped up on us. We can see the river from our windows. We used to get tin for our roofs and yarn for our traditional weaving from the government. But in 1999, everything stopped.”

Villagers told Newslaundry that the government had been well-aware that government schemes could not continue once the area was notified as a national park. The government should have relocated them immediately, but failed to do so.

“We were ignored from the start,” Ramakanto said. “Now, we are left in a desperate situation.”

In his cramped home, a small box lies at the far end of the room. Ramakanto pointed towards it and said, “This solar energy box is the only government scheme that we have received in the last two decades, other than the ration card. Everything else has stopped. Even the only school left in the village is in shambles.”

A single classroom

Dodhia has one English-language middle school run by the government. It serves four other villages – Mohmora, Tengabari, Sarisuti and Kuli Gaon – and comprises three teachers, one room, and around 100 students from Classes 1 to 8.

Ramakanto Das, who teaches science at the school, told Newslaundry that children here are severely impacted in terms of their physical and psychological well-being.

“In one room, we have to accommodate and teach students from Class 8 all the way down to Class 1,” Das said. “The same classroom is used as our office and storeroom for the materials to give them their midday meal. There used to be another building but it is in ruins because of the floods. All sanctions for buildings in this area were stopped more than a decade ago and so, we have to make do with what we have left.”

The three teachers in the school live in Dibrugarh. “It takes us three hours by water to reach the school,” Das said. “During the floods, there is no way to reach.”

Given their way of life, there’s a huge gap between what the children study and what they experience, he said.

“Right now, for example, they have books on science and technology but here, the children have never seen it in real life,” he said. “When they have to try and comprehend what a washing machine is, or what an air conditioner is, it’s beyond their social reality. This is the cost of living in such a remote area.”

If this goes on, he added, the children will not have a future.

Ramakanto Taye’s son Janto Taye accompanied this reporter as we left Dodhia. He cradled his infant daughter in his arms before we walked towards the boat that would take us back to the protest site. We climbed into the boat and set off.

After a few minutes of silence, he said: “We cannot raise our children here. We also want to live, not just survive. We are human. There is a constant threat to our children’s lives here. The floods have made a situation that was already grim even worse. Which is why we will continue to protest until we are rehabilitated somewhere safe and sustainable.”

The right to be rehabilitated

Back at the protest site, Anita Mili, 19, told Newslaundry that she came to protest in December with her aunt. She hasn’t seen her parents, who stayed behind in Laika, since then.

Anita left school when she was 16 because her family could no longer afford to send her across the river to the high school.

“The last school in Laika was washed away last year,” Anita said. “The river is taking away everything and the land left behind in Laika is not good. But I don’t hate Laika. It’s nice, and it’s my home. If you go there, bring me back some bogori. I miss it.” Bogori is a winter berry popular in Assam.

Given this history of broken promises, it’s unsurprising that the residents of Dodhia and Laika aren’t sure if they’ll finally be rehabilitated this time around.

“We have a right to be rehabilitated to good land,” Prasanna said. “We don’t want to steal land from anyone. We just want the government to give us land suited to our identities as forest villagers.”

And so, he said, they will wait.

Newslaundry reached out to Tinsukia district commissioner, Diganta Saikia, for comment but received no response.

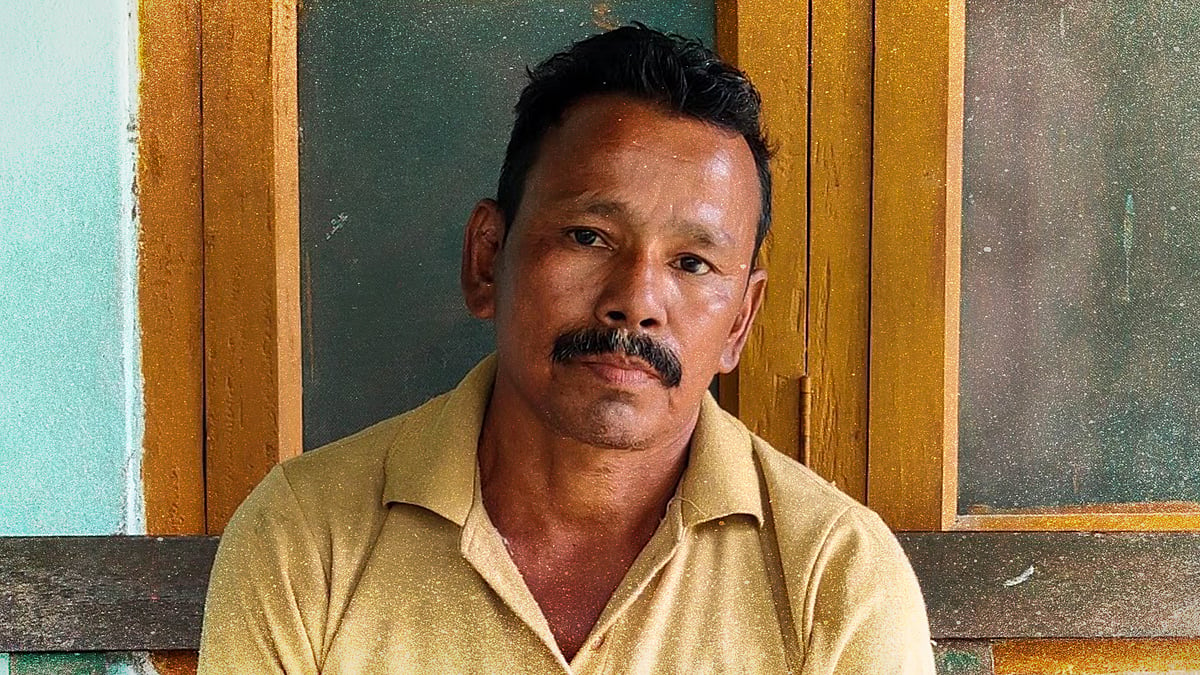

All photos by Supriti David.

Treacherous river: How the Brahmaputra is eroding away lives and livelihoods in Assam

Treacherous river: How the Brahmaputra is eroding away lives and livelihoods in Assam Baghjan fire is out. What’s happened to the Assam villagers ruined by it?

Baghjan fire is out. What’s happened to the Assam villagers ruined by it?