Mamata vs Modi: Competitive populism will be the flavour of Bengal’s Assembly poll next year

Mamata’s governance will work in her favour, while the BJP will have to focus on developing its weak state leadership.

Amidst the devastating pandemic, Indian politics is still as evergreen as it can be. Not even a crisis of this scale can force our politicians to concentrate on the welfare of the public. The toppling of state governments, the Central Vista project, the hounding of faces of dissent — this is how the authorities create their symbols of power.

Within a year from now, India will witness two Assembly elections which will, in a way, be a tentative report card for the incumbent government. The public will judge the performance of both the central and state leaderships in tackling the pandemic and other regional issues.

The two states are Bihar and West Bengal. In the case of Bihar, the political arithmetic remains monotonous and status quoist. With the hue and cry of the Mahagathbandhan vs the National Democratic Alliance, there’s perhaps fewer complications in Bihar in comparison to West Bengal.

Competitive populism

West Bengal’s upcoming Assembly election, scheduled for next April, will be interesting not only due to the electoral tussle, but also because of the ideological confrontation between its participants. The electoral tussle is due to the recent saffron surge in the state, while the ideological one is because of the gradual Hinduisation of Bengal’s society.

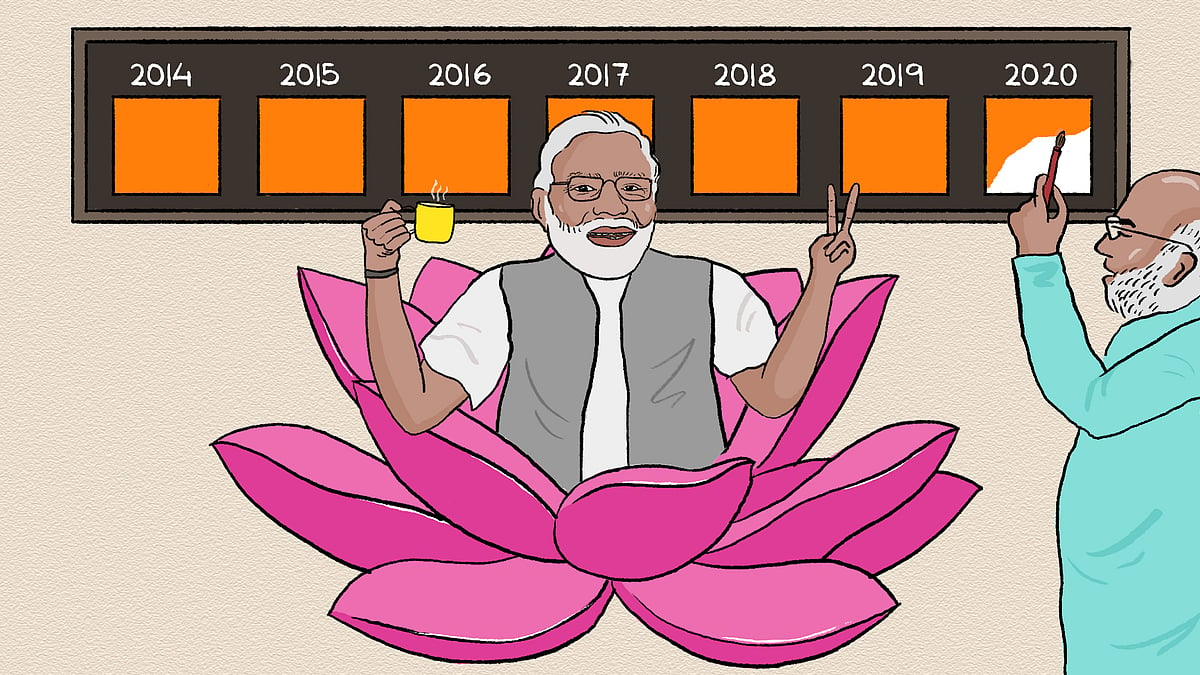

More than anything else, it will be a confrontation between two variants of populism: Narendra Modi and Mamata Banerjee. There are similarities and differences here. They both have complete command over their respective parties. Both the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Trinamool Congress are a show of one-upmanship, with an almost absence of any formidable voices within the parties. Second, both Modi and Mamata have “subalternised” politics to a large extent, by breaking the shackles of the liberal elite milieu in the form of the Congress and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in the centre and state, respectively.

To put it simply, both leaders have huge legitimacy from the people in their spheres of influence.

The differences in their populism accrue from the organisational machinery. For Modi, the BJP, and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, it’s the ideology of Hindutva that provides strength to the organisation. For Mamata and the TMC, the ideology is more personality-driven in comparison to the former, since she has a history of aligning with the Vajpayee government and was an important minister in the United Progressive Alliance government.

Mamata’s personality overrides her party. It’s as if Mamata is the ideology, the party, and the politician. The degree of over-centralisation makes the case for Mamata being more appealing among voters in Bengal. Taking the nitty-gritty of governance seriously, she’s had tangible developments as far as some policies are concerned, such as Kanya Shree, which seeks to improve the status and well-being of girls, and the provision of food grains for Rs 2 in the poorest districts through the public distribution system. On a symbolic level is the installation of trident streetlights, live broadcasting of administrative meetings, and her government’s populist budget this February. Mamata has managed to market these policies well, driven through her straight-cut appeal to the public.

While Narendra Modi is undoubtedly the most popular leader in the country, his personality cult will have to compete with Mamata’s brand of populism. The BJP’s central leadership is not well backed by its state leadership, the latter being less receptive to passing on the message of Modi at a wider level.

The BJP’s state leadership in West Bengal lies mainly in the hands of two people, Dilip Ghosh and Kailash Vijayvargiya. It’s heavily dependent not only on components of the central leadership but also popular icons of Bengal like Swami Vivekananda, Subhas Chandra Bose and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee. This interdependence gives Mamata an advantage as this, in a way, shows the absence of any alternative.

Dilip Ghosh, being an incumbent MP from Medinipur, could not lead his party from the front, which led to the BJP’s abysmal performance in constituencies of South Bengal in comparison to North Bengal. This is where Modi’s development narrative, along with the Hindutva ideology, clicked in the recent Lok Sabha poll.

At the same time, Kailash Vijayvargiya, being imported from Indore, completely lacks personal equations with the public. He was brought to Bengal due to his hard Hindutva posturing, which delivered results in the recent Lok Sabha election. But it goes without saying that regional equations will be at the forefront in the Assembly election.

Moreover, Mamata in her recent virtual rally tried to antagonise the BJP’s state leadership by distinguishing between Bengali and Gujarati. She made her point that Bengal will be ruled by Bengalis, not an “outsider” from Gujarat.

Secondly, Mamata herself has been engaging in damage control. Known for her steadfast fiery attitude, she was criticised by both the regional and national media in the context of freedom of expression. In 2011, when she became chief minister, she couldn’t handle the heat of tough questions from some students and left, while branding the students as “Naxals” and “Maoists”. From that Mamata to the one we see today, one who’s now willing to call for an all-party meeting in the state after the outbreak of the pandemic — she has evolved. Now, she’s everywhere: briefing the press regularly on Covid, giving a personal touch to social distancing arrangements and the rescue operations following Cyclone Amphan. This is a populist trademark of any strong leader who believes in direct connection with the people, bypassing bureaucratic protocols and norms.

Thirdly, in pre-Covid times, an over-reliance of the BJP on Hindutva in the form of the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizens made some sense with Bengal’s public due to feelings of anti-incumbency. But in a post-Covid world, the RSS and BJP might miss their shot in streamlining their efforts to saffronise the political landscape. The debate over the citizenship law is no longer at the forefront.

Which way can Bengal go?

In most of the post-Independence period, Bengal took an anti-Centre stand. With Mamata, similar politics continue. It’s not wrong to argue that she’s one of the most formidable oppositions to the BJP in 2020.

The dearth of the BJP’s state leadership can also be understood by the role of Bengal’s governor, Jagdeep Dhankhar. His interference in appointing vice-chancellors of state universities and his continuous attempts to highlight a different centre of power through his constitutional position has generated further anxiety and confusion among the public.

Mamata’s regime is standing on her government’s policies, which will be tested in the upcoming election. In 2016, economist Jean Dreze recognised the enormous work by the Bengal government regarding the public distribution system since the passage of the National Food Security Act in 2013. This has, to an extent, percolated down to the poor and migrants in the post-pandemic phase. Further, her recent announcements at the virtual rally to provide food grains for free if she returns to power makes her case strong and appealing.

Regionally, North Bengal will be an important area to observe, and will be decisive in the upcoming election. The BJP’s remarkable performance in seven out of eight districts in North Bengal is the major reason for the huge saffron surge in the state.

While Modi-Shah are trying hard to sell their crucial Ayushman Bharat healthcare scheme, Mamata has its replacement ready in the form of Swasthya Sathi, West Bengal’s health policy, with more focus on the primary sector. By placating the Rajbanshi community in North Bengal to inducting Chhatradhar Mahato into the Jangalmahal unit of the TMC, Mamata is trying hard to restore her party’s image in the region.

Mamata’s populism and governance on the one hand, and Modi’s populism with a weak state BJP leadership on the other, makes a complex case for Bengal. Which way Bengal will swing depends on the handling of the current pandemic by both personalities in their spheres of influence. Regional issues will play a part, and both parties are already attempting to score points.

***

The media must be free and fair, uninfluenced by corporate or state interests. That's why you, the public, need to pay to keep news free. Support independent media by subscribing to Newslaundry today.

6 years, 2 months, 4 days: Modi’s term marks the longest uninterrupted non-Congress government at the centre

6 years, 2 months, 4 days: Modi’s term marks the longest uninterrupted non-Congress government at the centre