Why newspaper obituaries should not be a metric for a pandemic’s scale

One, significantly more obituaries is not a phenomenon observed across all major papers. Two, it ignores social factors to draw a conclusion.

In 2005, as part of research for a book, media critic Sevanti Ninan interviewed Sudhir Agarwal, the managing editor of Dainik Bhaskar, one of India’s most-read newspapers. During their conversation, Agarwal said something that would uncannily take on new meaning during 2021’s pandemic.

He said that the newspaper had decided to use the money earned as advertisement revenue for obituary notices in their pages to improve crematoriums in the cities where Bhaskar had its editions. Consequently, the paper donated Rs 70 lakh to this cause, earmarking Rs 1 lakh – its monthly collection from publishing obituary notices – towards this purpose every month. Additionally, Bhaskar also used the money to run a cremation centre in Bhopal.

When Ninan’s study of different aspects of the Hindi press, Headlines from the Heartland, was published in 2007, Dainik Bhaskar’s initiative was analysed as part of boosterism – something that the increasingly competitive market for Hindi publication was seeing amid circulation battles.

A decade and a half later, the Covid pandemic has brought a poignant intersection and ironic turn to the newspaper’s decision: overburdened crematoriums and multiple pages of obituaries in the Jaipur edition of Dainik Bhaskar.

However, the space given to obituary notices in just one of multiple editions of a leading Hindi daily cannot be taken as a metric to gauge the scale of the pandemic’s death toll. Moreover, other leading Hindi dailies and different editions of Dainik Bhaskar itself have not shown any significant spurt in the number of obituary notices to suggest a pattern across publications in the Hindi heartland.

In the last five days of this week, for instance, scanning the state capital editions of major Hindi dailies – which cater to readership in major heartland states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand – does not reveal a major rise in obituary notices, nowhere close to what was seen in the Jaipur edition of Dainik Bhaskar. The same holds true for editions in Delhi. None of the publications had to extend obituary notices to the entire eight-column space, and that too on multiple pages.

If one looks at the top three dailies of the heartland – Dainik Jagran, Dainik Bhaskar, and Hindustan – they jointly present a microcosm of trends. Jagran is India’s most read daily followed by Bhaskar, and Hindustan has the highest circulation in Bihar and high circulation in Uttar Pradesh.

However, some state-specific major publications are also important, such as Rajasthan Patrika in Rajasthan and Prabhat Khabar in Jharkhand.

For reasons of visibility and, perhaps, concentration of the obituary-placing demographic of the readership, the capital editions of major states – Lucknow, Patna, Bhopal, Jaipur, Raipur and Ranchi – in the Hindi heartland can be used as representative editions to study the trend over the last few days. With the exception of the Jaipur edition of Dainik Bhaskar, there is little to suggest any major surge.

This is underlined more strikingly by the fact that even other state capital editions of Dainik Bhaskar – Bhopal, Patna and Raipur – do not show any significant increase in the number of obituary notices, even though Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh reported a high number of Covid cases. It should be noted that Bhaskar does not have a presence in Uttar Pradesh.

Apart from its Jaipur edition, Bhaskar’s editions in cities like Jodhpur, Alwar and Kota did not see a rise in obituary notices.

With Dainik Jagran too, there was no major spurt in obituary notices. Since Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Delhi constitute a major chunk of its readership, this is important in the context of misplaced efforts to use obituary notices as a metric of the deadly spread.

Hindustan, the market leader in Bihar, also did not see a major rise in homages. Among other factors, this is understandable in light of the fact that despite being the third most populated state in India, Bihar has seen relatively fewer deaths than other large and populous states.

If we look at leading English dailies – the Times of India, the Hindu and Hindustan Times – there are no multi-page obituary notices. In TOI and HT, none of their big city editions – Chennai, Mumbai, Delhi, Bengaluru, Kolkata – or state capital editions – Lucknow, Bhopal, Patna – had remembrances or tributes extending to a number of pages. However, given that their readership base is more likely to spend money on placing obituary notices in newspapers, this trend runs counter to such an assumption.

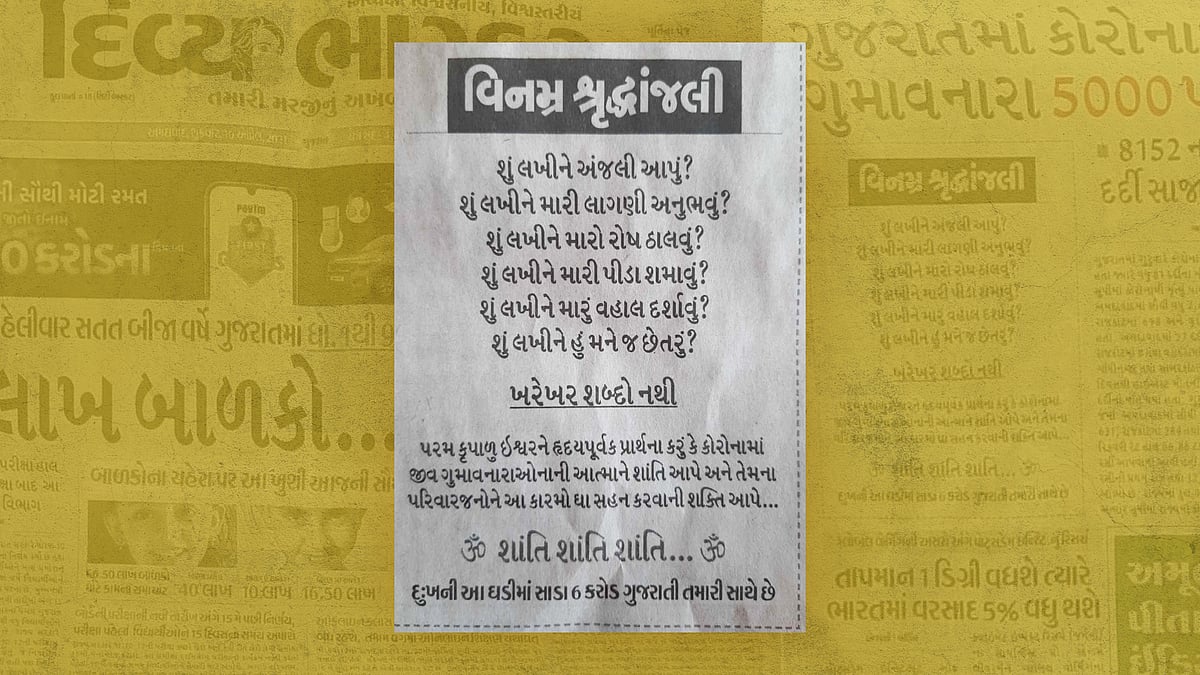

On the other end of the spectrum, social media users are taking note of the surge of obituary notices in Gujarati press publications like the Bhavnagar edition of Saurashtra Samachar.

There is also the question of segregating tribute messages for victims of the pandemic and those who passed away due to non-Covid cases. Moreover, as most of the tributes in Dainik Bhaskar’s Jaipur edition show, mourning families are trying to make it a part of public communication that formal gatherings will not be possible due to social distancing norms. As mourning in a ritualistic setting is as much a social function as an individual response, a formal message in a public space – on skipping the ritualistic aspect during the pandemic – could be an explanation for the surge in obituary notices in some dailies.

But coming back to the Hindi press, any attempt to find a correlation between the scale of the scourge and the space occupied by obituary notices in newspapers misses some crucial sociological aspects.

To a large extent, booking print space for placing tributes is limited to a section of the upper middle class or even elite in the vast swathes of the Hindi heartland. In fact, even in these sections, it’s limited to a set of families who have some interface with evolving mores of formalised grief in an urban setting. In urban spaces, a significant number of these families are more likely to place obituary messages in state capital editions of English dailies or even messages drafted in English placed in Hindi dailies. But there is one more significant strand to it, and that has as much to do with evolving social responses as with the space marketing drives of leading Hindi dailies.

This takes us to an emerging section within the middle class, in which booking space in newspapers for obituaries or messages is pitched as an aspirational value, even a symbol of upward social mobility. Stringers or local informants paid by newspapers in remote areas also double up as advertisement-booking agents who either sell the idea of placing obituary notices or tap into a latent urge for public communication. In her book, Sevanti Ninan talks about an uncle-nephew duo who worked in these twin roles for rival publications in Rajasthan: Dainik Bhaskar and Rajasthan Patrika.

This could also be seen as a form of expenditure that could be expected from the millions of readers that were added to Indian language newspapers, particularly Hindi dailies, in the last few decades. The social factors as well as implications of this growth, for instance, in the last two decades of the last century were addressed by media scholar Robin Jeffrey in his work India’s Newspaper Revolution (Palgrave, 2000).

Any exercise in using obituary notices in the print media as a measure of the pandemic’s lethal reach is neither supported by what one sees in a wide array of publications nor by the sociology of space-booking in Indian newspapers. In essence, drawing inferences based on such pages in a few select dailies is defined by a tendency to grab a defining image of the unfolding tragedy. Such hurry loses sight of the social dynamics of grief-messaging in the country and the diverse space of print publications.

Covid fallout? Gujarati papers are filling up with obituaries

Covid fallout? Gujarati papers are filling up with obituaries Gujarati paper writes moving obituary for state’s Covid victims

Gujarati paper writes moving obituary for state’s Covid victims