Riverside graves of the Covid dead tell a story of the media’s failure

And of a crisis of economic distress and hunger that’s gone largely unreported.

The defining image of this second wave of the pandemic in India has now become the hundreds of shallow graves along the Ganga and other rivers, replacing the searing images of burning pyres. These graves are a stark reminder not just of the discrepancy in death data between the official and the actual, but they also hint at a deeper distress in rural India that has been obscured from our view.

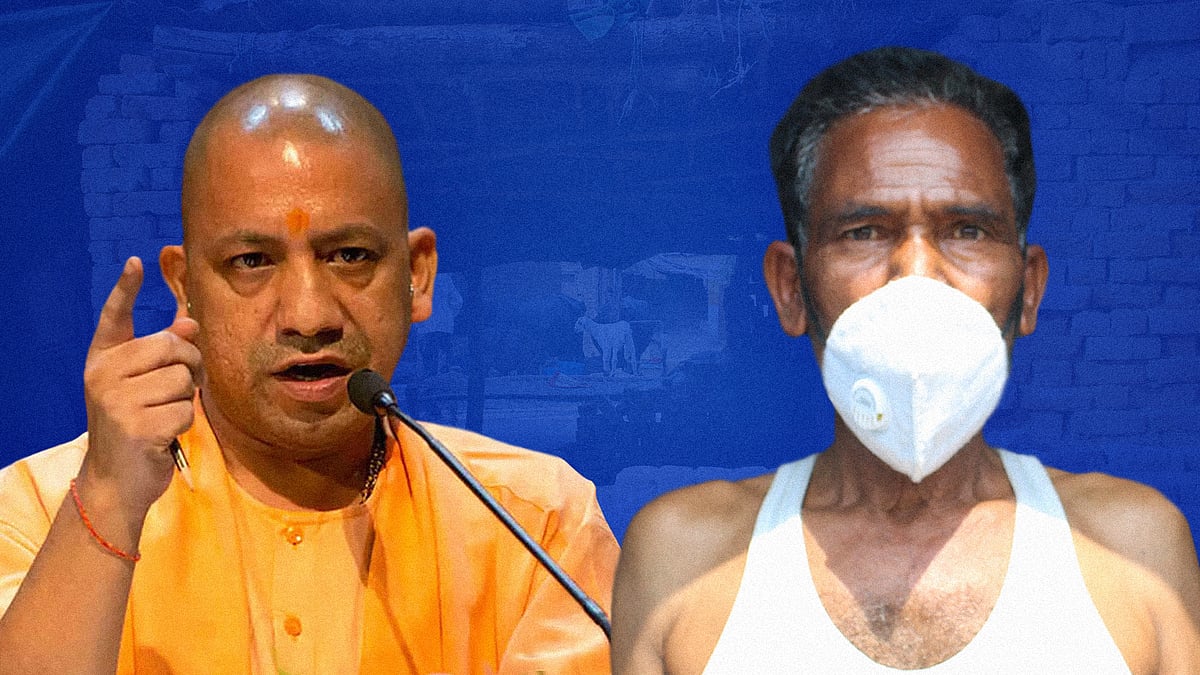

We have to be grateful that there are journalists who continue to doggedly pursue this sad and disturbing story of unaccounted deaths. From journalists going around in a car, filming these graves and recording what people have to say, such as Barkha Dutt, to mainstream regional media outlets like Divya Bhaskar and Sandesh in Gujarat refusing to obfuscate and telling the story as it is, to young women journalists like Shivangi Saxena and Akanksha Kumar from Newslaundry, such documentation will form an essential part of the history of these terrible years. Without this, there would have been a veil of disinformation pulled over the eyes of citizens. And false narratives, so beloved of this government, regularly amplified by the media groups beholden to it. And Uttar Pradesh chief minister Adityanath, who continues to maintain that all is well in his state where these shallow graves abound, would not have been called out.

Try as it might, the government simply has no place to hide now as journalists, experts and the international media continue to focus on the discrepancies in the data on deaths and incidence of disease. The latest of these is a data presentation by the New York Times that asks, "Just How Big Could India’s True Covid Toll Be?" Its conservative estimate is that there have been six lakh deaths from Covid but says the more likely number is 16 lakh. The official figure on May 24 was three lakh deaths. That is the extent of the discrepancy.

Indian newspapers have also been writing about this, with Chinmay Tumbe, author of The Age of Pandemics, looking closely at Gujarat's data in the Indian Express and Rukmini S writing about Chennai in the Hindu. Tumbe concludes that "even the most conservative extrapolations from the available excess mortality data take the all-India death toll of the second wave to over a million”. In sum, all these articles are saying the same thing, that both the extent of the spread of the virus and the deaths resulting from it are far in excess of what is revealed by government data.

Even if we were to assume that this is not being done deliberately, in the face of growing evidence, one would have expected a word of acknowledgment from officials that something has gone wrong and needs to be corrected. Instead, there is silence. Or efforts to divert the conversation elsewhere, to "positivity", which in the current context is just another term for denial.

The fact remains that while some newspapers, digital platforms and a couple of TV news channels have focused on this data mismatch, much of mainstream Indian media is not highlighting these facts.

Perhaps Manoj Kumar Jha, the Rashtriya Janata Dal member of the Rajya Sabha, is wrong to brandish the entire Indian media in a scathing oped in the Indian Express when he writes that it has "asphyxiated democracy at a time when the breathless nation is struggling hard to save its loved ones”. Yet, it is difficult to argue against his reflection that "mainstream media houses shamefully defending the indefensible must remember that the annals of history shall be much more objective and ruthless in judging their role than the system to which they are plugged into for reasons known to everyone. They amplified the discourse of the failure of 'the system', giving much-needed leeway to those who have knowingly imperiled the lives and livelihoods of millions of people. Instead of identifying, highlighting specific governance failures, and seeking accountability, the mainstream media is following the command of the faces behind the system as they enjoin people to 'talk positivity', 'spread positivity', etc."

Besides the story about inaccurate data on Covid deaths, the saffron shrouds on those shallow graves are obscuring another story that we in the media need to be reporting. That of immense economic distress and hunger that is leading families to abandon their loved ones in these shallow graves rather than conducting the ritual cremation. It is not difficult to imagine the extent of poverty and desperation if people cannot rustle up a few thousand rupees to buy wood and pay a priest to conduct the ritual.

A hint of this distress is coming through in some reports. But while economists will analyse the reasons for this continuing economic distress, it is for journalists to put a name and a face to it.

Last year, the migrant exodus gave us many faces to remember of the millions of people who subsist at the margins in this country. It was a story that was in your face; it could not be ignored.

This time around, there is no drama of that kind. Yet it is dramatic in its own way because it tells us that a year down the line, millions of families are broken, with no hope of finding a source of income, and little by way of government assistance to tide them over. Compounding this is their continuing invisibility in mainstream media reporting.

This story by Supriya Sharma in Scroll, for instance, paints a grim picture of what urban migrants are facing at this time in our big cities.

She writes, "If the lockdown last year came down as a hammer, this year, it feels like a thousand cuts. Obscured by the dramatic and distressing images of death in the second wave of the pandemic, a slow drip of distress is going unnoticed, not just by the government, but even by other citizens, leaving the urban poor to fend for themselves."

The migrants who left last year came back to the cities after their long trek home, only to be left high and dry once again. And this time, as Sharma records, civil society interventions appear more muted. I would argue that this has happened because their distress has been rendered invisible by the media. Without us digging out and amplifying this story, there is no hope for people living perennially on the margins to get either government aid or that from voluntary groups.

Sharma also reports on how even what the urban poor are entitled to, such as extra rations under different state and central programmes, is not available. To cover daily expenses, people are compelled to borrow money, probably at usurious rates, just to be able to buy provisions on the open market at much higher prices than they would have got if the ration shops had the supplies. The central government is failing not just on the vaccination front, it is also proving incompetent in executing the welfare programmes which have been in place for more than a year.

Anshu Gupta, founder of the organisation Goonj, also emphasises the crisis of hunger in this article in the Indian Express. He writes that last year the poor gained attention because the media reported on the exodus, but as soon as they reached their villages they were virtually forgotten. This time around, the crisis has focused on the medical emergency, on the need for oxygen and medicines. But the crisis of deepening hunger has been virtually overlooked by everyone, including the media.

Gupta writes, "It is important to understand that while the second wave is about health, it doesn’t mean that hunger is not an issue. The second wave is about ventilators and oxygen to keep people alive, but...for millions today, access to simple dal chawal is no lesser than access to oxygen.”

It is also more difficult to provide assistance this time around because with trains and buses still functioning, many migrants left voluntarily for their homes. We know now that part of the reason for the spread of the disease to rural areas was because the system of quarantining returning migrants last year was not implemented this time around. As a result, they brought back the infection. And given the dire economic crisis facing their families, there was no one around to help or record either infection or death.

This is the story those shallow graves are telling us, one that still needs to be reported.

How Adityanath sold PR as Covid outreach in Moradabad

How Adityanath sold PR as Covid outreach in Moradabad Why are Unnao villagers burying their Covid dead by the Ganga?

Why are Unnao villagers burying their Covid dead by the Ganga?