What Dilip Kumar taught a generation of men about the brooding quiet

His legacy was far beyond that of a ‘tragedy king’, offering grace in the spoken word and restraint in speech.

To remember Dilip Kumar is to feel the brooding pause, the essential decency of it. That’s remarkable for a man who spoke with chaste diction. As an afterthought, one also recalls that he acted with a craft that only a few cared about in the early years of Hindi cinema.

But the most defining, even radical, imprint of Dilip Kumar on screen was the dignity of silence; the unhurried moments in which he shone with a rare grace. When he spoke, the words found no good reason to beat time. They flowed at their own pace, almost hesitant about whether they were serving their purpose.

When Dilip Kumar began his acting journey in 1944 with Jwaar Bhata, he could have been anything in the formulaic world of commercial cinema, which prioritises style over craft. He chose to offer a blend of both and, in the process, emerged as a thinking man’s reflection on screen. It would be a travesty to limit his legacy to that of the “tragedy king”, the celebrated icon of the forlorn and the languishing.

The sheer body of his work, the pre- and post-independence periods it straddled, and his place as a harbinger of method acting in Indian commercial cinema made Kumar different things to different people. “Dilip Kumar is a legend by any definition,” wrote economist Lord Meghnad Desai without wasting a word in his work Nehru’s Hero: Dilip Kumar in the Life of India. There is also a temptation to see strands of a new republic led by a Nehruvian order and its key debates, as in Naya Daur (1957),or fault-lines, as in Footpath (1953).

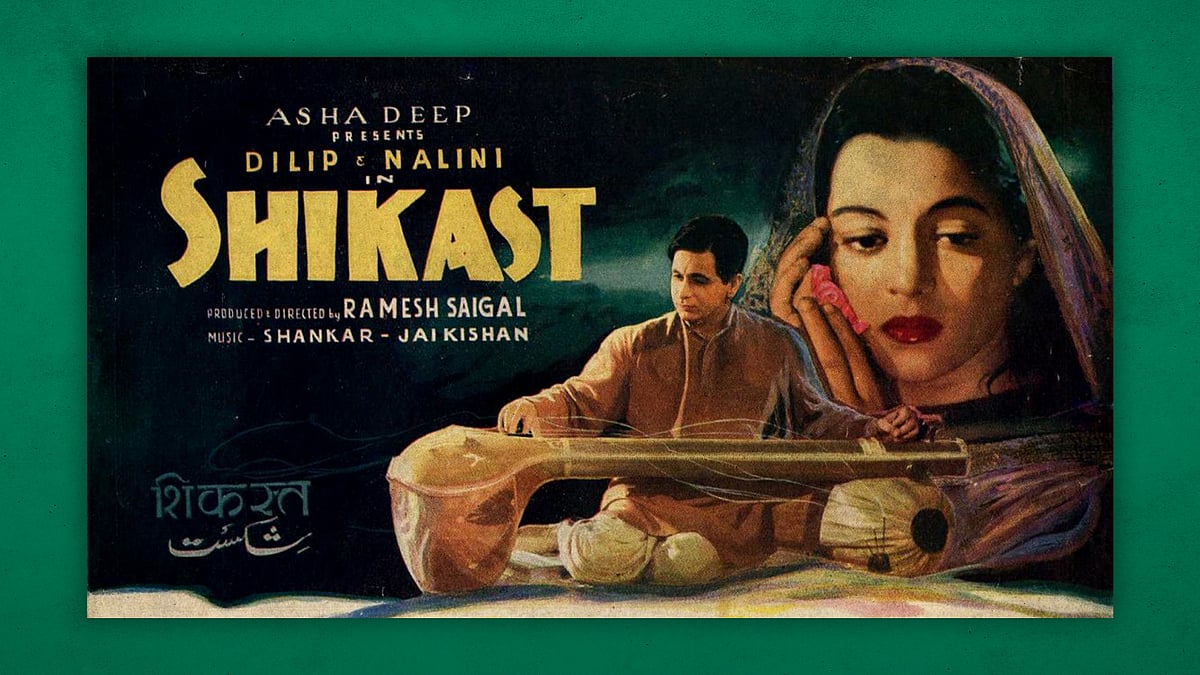

His portrayal as the suffering lover in films as varied as Andaz (1949), Jogan (1950), Shikast (1953) or even Amar (1953) somehow made him “pre-assigned” to play the most memorable of his tragic roles in Devdas (1955). It was made 20 years after PC Barua adapted the film for the screen in 1935 with KL Saigal in the lead. Kumar’s portrayal put him in a different league but it was also the last of his major attempts in enacting melancholy. This was followed by a widening of his repertoire in 57 films as the lead actor: the ruritanian character of a prince in Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and the conflicting shades in Ganga Jamuna (1961) being two of the more talked about among his other significant portrayals in the late ‘50s and ‘60s.

In a way, the only thread running through the diverse pieces of his work was that of an evolving ideal of Indian manhood in the first two decades after independence. It could be argued that in the realm of popular culture, as seen in Indian films, Dilip Kumar represented it more than any of his contemporaries. It went far beyond the sway he had as a good-looking screen presence. That is not to deny the fact that a generation grew up on his sartorial sense and hairstyle. In fact, he remains the only male actor who had a leading lady in a film admiring his looks with the song Ude Jab Jab Zulfe Teri in Naya Daur. However, more than any of his contemporaries, his body of work left a register of different responses of young male life. It was made possible by his craft in playing roles in milieus as diverse as a metropolis and a rural hinterland, and time as separated as the age of medieval empires and the contemporary life of a new republic.

The interplay of modernity and tradition, the impulses of desire and the despair of loss, and the understatement of sexual tension could be found in different forms in his portrayals on screen. The way he managed to present these in films like Jogan are as important as his role in films like Naya Daur where he enacted the anxieties of man-machine conflict in a largely rural country embracing industrialisation during the second plan period. While calibrating a delicate persona of response and poise in portraying each of these roles, Dilip Kumar became a point of popular reference. Despite being held back by the melodrama of commercial films, he could project the flickering of unsure thoughts and the brittle stages of a range of emotions. All this was done with such a sure finesse in dialogue delivery that it became a template for gravitas as much as it was a style guide for a generation of cine-goers.

The way a young man responded to various situations thrown up in a day could very well be the Dilip Kumar way. His screen projection set a pensive tone for youthful reflection without losing any of its popular appeal. In the process, it quietly shaped into one of the most lingering influences on male ideals of all time. To his credit, he made poise fashionable and silence eloquent.

In the times he lived and worked, Dilip Kumar was the much needed thoughtful pause in popular conversations. In his attempts to supplement style with the rigours of craft, he was an early harbinger for the pursuit of excellence in Hindi commercial cinema. In doing so, one of his many lingering legacies is that he made restraint in speech and the grace of spoken word gain popular currency. Perhaps an even greater achievement was the fact that with whatever one saw of him in his films, one conducted oneself like him without anyone realising. The quiet seeping in of life and its different shades in a cultured mind is so much a Dilip Kumar way.

Life in the time of pandemic: Revisiting Dilip Kumar’s Shikast and its subplot about the plague

Life in the time of pandemic: Revisiting Dilip Kumar’s Shikast and its subplot about the plague