In former Bihar DGP’s account, a solution-driven police career, eventful teaching detour

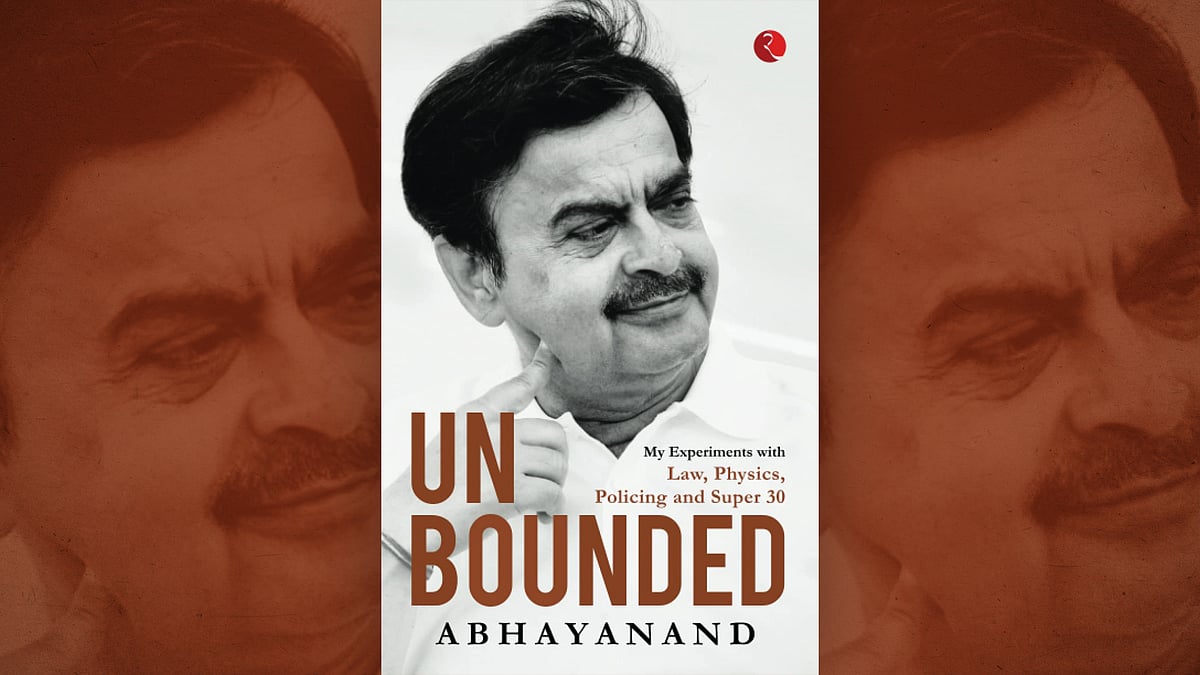

Abhayanand’s Unbounded relives a journey at the intersection of policing, law, science, and pedagogy.

More often than not, the memoirs of civil servants are fraught with risks of weaving personal accounts into a larger canvas of the public realm. And it isn’t unusual to see such exercises get stuck either within cautious tones and guarded memories or narrations from a conceited perch of the governing elite.

Even though the dyad of ‘high power and low-key presence’ in public life goes into the making of the exalted ethos of the services, the trappings of visibility and public gaze have only grown manifold in recent decades. One has to be more alert to such lures especially when a man reflecting back on his life was in public view for donning two hats: one of a top cop credited with the turnaround in law and order situation in Bihar in the first decade of the present century and the other of a physics teacher who worked on the Super-30 initiative training an underprivileged group of IIT aspirants.

But to a large extent, in his autobiographical account Unbounded, published by Rupa Publications, Abhayanand, the former director general of Bihar police and a physics teacher known for Super-30, has steered clear of such traps.

While the book sometimes strays into self-congratulatory notes, the account is mostly engaging for reliving a journey which found itself at the intersection of policing, law, science and pedagogy. In the process, the author also draws on his more than three decades of hands-on experience to offer a social and economic dissection of crime while placing it within the ambit of the responses from citizenry, civil society and the state apparatus.

As a second generation IPS officer, Abhayanand doesn’t lose sight of the elements of continuity and change in the conduct and public esteem of the police leadership in the decades following the country’s Independence. His father Jagadanand, an IPS officer of 1951 batch, had also risen to the post of the Bihar DGP, and was a part of a generation of police officers in the formative years of Indian republic which was entrusted with a role that had the glow of a fresh constitutional mandate.

In some ways, as an IPS recruit of 1977 batch, the author laments the gradual erosion of the public faith reposed in the service, a part of the all-India services mentioned in Article 312 of the Indian constitution. By the time he retires, 37 years later in 2014, he traces the sense of pride missing in most of the new crop of police officers.

Abhayanand refreshingly avoids the platitudes of political interference and corruption-inflicted inefficiency plaguing the working of the police force. Instead, the author perceptively, and forthrightly, grasps the problem of the rupture in police-public ties. He is of the view that as far as the citizenry values the integrity of the police and supports the officers, other externalities are neutralised and all forms of interventions nullified. That’s why he exhorts everyone forming the police force – from the constabulary to officers in higher echelons – to elevate their work to a level that invites public support, which in turn, will also bring general compliance and public obedience of law and order measures.

In offering such insights, the author dwells on his decades – ranging from his stint as a young SP in districts such as Madhepura, Aurangabad, Sahibganj, Nalanda and Bettiah to subsequent tenures such as DIG, IG, ADG and DGP. He places high value on the creative use of law to navigate the challenges of countering crime as well as building strong cases to convict perpetrators and masterminds alike. As a police officer, his account is sprinkled with a number of episodes where the focused use of already available legal provisions helped him overcome obstacles as well as thwart any attempt at external pressure.

In placing the majesty of law as the keystone of police functioning, he identifies the law as not only the main weapon of the police but also its shield. That’s why, as the ADG (headquarters), a large part of his prescription for restoring law and order in Bihar was reinstating the reverence for law, not the awe of the police. Contrary to what a section of public opinion, including that among the political class, suggests about police crackdowns for restoring law and order, he favours a more robust legal application and enforcement. That, for instance, is evident in his reliance on the meticulous application of the Arms Act for reining in crime in the middle of the first decade of this century, a period when Bihar was trying to extricate itself from the anarchic notoriety of “jungle raj”.

Besides foregrounding law, the former police chief has also reflected on the key role that rigorous investigation should play in policing. He bats for bringing more scientific processes to investigations to make the process compact, accountable and able to stand all forms of judicial scrutiny. In 2006, hearing the Prakash Singh vs Union of India case, the Supreme Court had gone to the extent of suggesting that one of the measures for improving policing could be the separation of investigation from regular law and order functions of the police.

In a state where crime is said to be entrenched in the political economy and the social matrix underpinning it, decades of experience in the police brass has also made Abhayanand turn his gaze to these facets of the criminal psyche and locate it within the social milieu. He has elaborated on the essential economic nature of different forms of crime, and wrestled with the questions of why some known criminals stay poor while a number of wealthy people have no visible source of income but continue to be prosperous.

In some of these detours that Abhayanand makes, he tries to decode white-collared crime with the concept of ‘social laundering’ – a means of upward social mobility where criminal and corrupt elements may earn social respectability by positioning their wealth. In a way, it’s an idea that in a kleptocratic set up resembles the conversion of economic capital into the social capital of the powerful. In some ways, it also reminds one of what scholar Arvind N Das had hinted at in his work The Republic of Bihar (1992). Das had argued that in the absence of other productive avenues of investment, a sizable section of the propertied class in Bihar had sought crime as a site of investment.

As a later strand in his journey, Abhayanand’s innings as a physics teacher has quite understandably been confined to one chapter. As he turned his initial need to teach physics to his two children for IIT- JEE, the Patna Science College physics graduate thought about expanding this exercise to the idea of Super-30, an initiative to teach a promising batch of aspirants from the deprived sections of society. He talks about the later disillusionment with the initiative as it acquired a commercial orientation. But, Abhayanand did persist with other off-shoots of the same idea like Rahmani-30 and Magadh-30.

Even as one of his early collaborators, Anand Kumar, was celebrated in a Bollywood movie and TV news shows, popular culture lost sight of critical appraisal. The former police chief alludes to the fact that there was lack of proper scrutiny of the tall claims and administration.

“No one tried to probe into the tall claims made by the organisation and how it was being run. Transparency steadily became a casualty till Super-30 , in its original form, died a natural death. The essence of experiment, however, survived,” he writes.

In its narrative expanse, Unbounded offers a social register in which a former police chief’s trajectory in enforcing law and nurturing order intersects with the pedagogical call of teaching physics to young engineering aspirants. In doing so, Abhayanand mostly avoids the hand-wringing polemics about systemic constraints on policing and comes up with hands-on solutions instead. That adds as much empirical heft to his account as as his eclectic range of interests – a riveting blend of someone enforcing the laws of legislature and teaching the laws of physics. A bit of blue-pencilling, however, could have done away with some of the repetitive flab in the book, perhaps the kind of verbal excess that comes while looking back at decades in a life in the public realm.

NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.