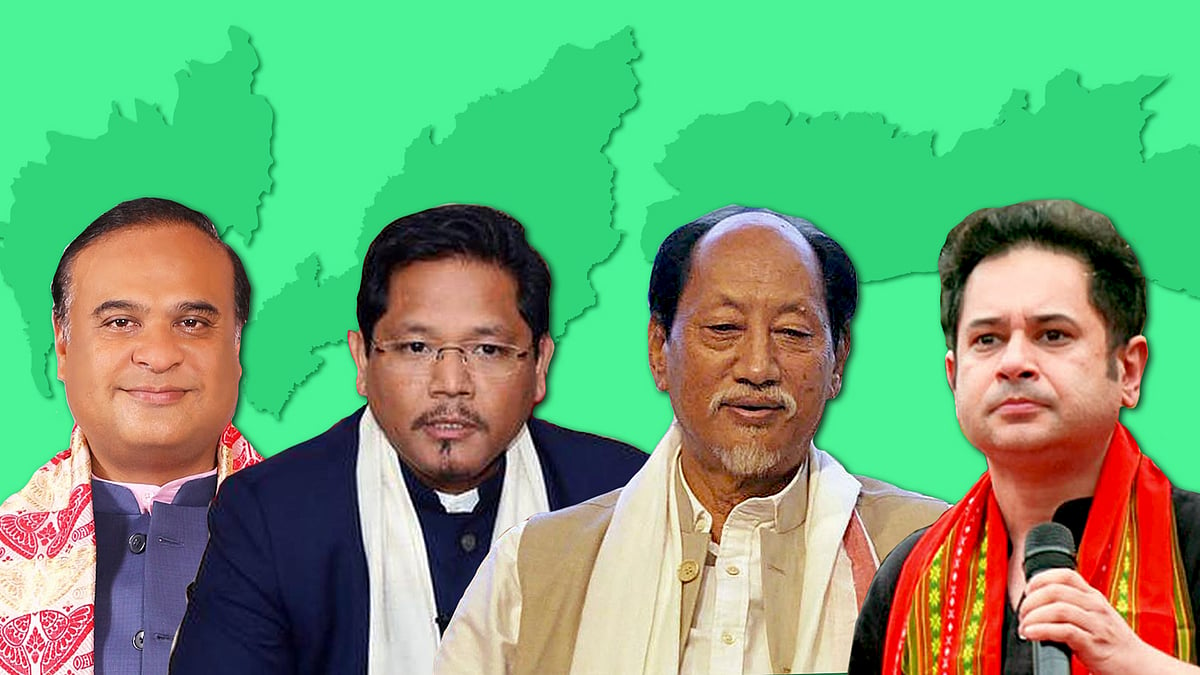

Hindu nationalism and local sub-nationalisms: Northeast poll results show rise of two poles

Twists may come in government formation, or later, as regional forces strive to defend their turf, keep out the BJP and its allies.

There may be plenty of individual surprises in the assembly election results from three Northeast Indian states, with several upsets. There are, however, no apparent jaw-droppers so far as the larger political picture is concerned.

In Meghalaya, the ruling National People’s Party has emerged comfortably as the single largest, as expected. Although it contested the polls on its own, its alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party is already back in place, with the BJP formally issuing a letter of support for the formation of the next government in the state. In Nagaland, the National Democratic Progressive Party and BJP alliance has secured a majority, which is also entirely along expected lines. In Tripura, the BJP has overcome the combined challenge of the Congress and Left – and even this is not really a surprise.

This may be taken as an endorsement of the BJP by voters in Northeast India, but the devil is in the detail.

Nagaland is a state with an 88 percent Christian population and a storied history of armed insurgency dating back to at least 1954. The real substance of its politics has for decades been in the struggle between independence from India and political accommodation within the country. This still remains the case. The plank on which the NDPP and BJP were in power, and have returned to power, is the successful conclusion of what is known in Nagaland as the “Naga political issue” – the peace talks with Naga rebels that have been going on and on for the past 26 years and counting. All other political issues in Nagaland have usually been seen as secondary to this.

The previous elections, in 2018, saw a call to boycott the polls initially endorsed by a group that included representatives of 11 political parties, including the NDPP, BJP and Naga People’s Front. The slogan was “solutions before elections”. The boycott call failed spectacularly in the end. The political class across parties was too deeply wedded to the benefits of power, and the voters themselves, accustomed to receiving gifts and hard cash for votes during election time, did not wish to miss the bonanza that comes once in five years. The slogan of “solutions before elections” was replaced with “elections for solution”. Voters participated enthusiastically.

Poll percentages in Nagaland typically range in the 80s, partly because someone is often there to cast a vote for an absent voter. This time, for example, the editor of the Nagaland Page, Monalisa Chankija, wrote about how she was surprised to discover after reaching her polling station that her vote had already been cast. When she complained about this, she was offered a solution: she could cast her vote in someone else’s name!

All the major political parties in Nagaland – except the Congress which had won zero seats and hence had no MLAs – had joined hands in 2021 for an opposition-mukt Nagaland assembly, claiming this was necessary to pave the way for the Naga political solution. This destroyed the credibility of the main opposition NPF which was the single largest party with 27 seats in the 60-member assembly in 2018. This time, it has been punished for its perfidy. Its tally is down to two. There is no credible opposition left in the Nagaland political mainstream. The space is occupied by parties with no base in Nagaland, such as the Nationalist Congress Party of Sharad Pawar, which with seven seats is positioned to be the principal opposition – unless the story of an all-party government and opposition-less assembly is repeated once again. A great disillusionment with the political class in general has existed and continues to exist. Altogether, 27 sitting MLAs across parties, including some big names, lost their seats this time.

This state of deep cynicism contrasts with the political conditions in Meghalaya, where a vibrant political contest exists in mainstream electoral politics. There, local and regional parties have performed very well, with the ruling NPP – despite widespread allegations of corruption hurled by all, including its ally BJP – winning 26 of the 60 seats to better its 2018 tally. It is followed by the United Democratic Party, another local party with a strong base in the Khasi Hills, with 11 seats. A new local party founded in November 2021, the Voice of the People Party, has won four seats on debut, which is a creditable performance. The BJP, which was expected to improve its tally, is back to the same number it held in the last assembly – two seats. The Congress, despite being destroyed by defections, has managed to win five seats, even though the party’s leader in the state, Vincent Pala, lost his own seat.

The twist in the tale comes in government formation.

The UDP was part of the last government but is reluctant to join this one. It faces competition from the VPP to represent the Khasi voice. Without the UDP, the NPP and the BJP are two MLAs short of the halfway mark. Those numbers can be supplied by either the Hill States People’s Democratic Party or the People’s Democratic Front, but both face the same dilemma as the UDP. There are parallel efforts underway to form a government led by the UDP, with support from the Congress, Trinamool Congress, and other smaller parties. Arithmetically, this is possible. Ideologically, Khasi sub-nationalism and secularism can combine to provide the justification. At the time of writing, it is not clear whether the NPP-BJP combine will succeed in cobbling together a majority.

The rise of local tribal aspirations is also a key theme in the results in Tripura. The BJP has managed to secure a majority on its own over a combined Congress-Left opposition. This is undoubtedly a big victory. It indicates that the Congress and the Left, which were traditional rivals in the state for decades, could not manage to combine their bases effectively, and have lost voters to the BJP.

In Northeast India, Tripura is the only state other than Assam with a clear Hindu majority, and it is also arguably more like mainland India than any of the hill states in cultural terms. The BJP’s growth in the state, although bolstered by political violence and misuse of state power, may therefore have deeper roots than it does in states such as Nagaland, where its rise is likely to last only as long as the BJP rules at the centre in Delhi.

However, the story of these elections in Tripura is the rise of not the BJP – which was already in power there since 2018 – but of the Tipra Motha led by Pradyot Manikya Deb Barman. For a party that is barely two years old, to win 13 seats in an assembly of 60 is a highly creditable performance. This becomes even more so when one considers that the politics of the Tipra Motha, which stood strongly for tribal aspirations and a separate Greater Tipraland state splitting the current Bengali-dominated state, meant it was primarily in the fray in only the 20 constituencies reserved for Scheduled Tribes. In those seats, it has trounced the Indigenous People’s Front of Tripura, the local party representing tribals which was in alliance with the BJP.

The past few years have seen major political turmoil across Northeast India sparked by the National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Act. At the same time, a politics of “connectivity and development” has become well entrenched since the past two decades in this previously “backward” region. Opposing desires and contrary fears are in contest. The election results in the two states where electoral politics has genuine meaning – in Meghalaya and Tripura – reflect this.

The writer is a journalist and author. His next book, out later this year, is a political history of Northeast India.

NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.