CBI is 60 years old, but it’s still waiting for all-India jurisdiction

So far, the agency is subject to the whims of state governments.

On April 1, the Central Bureau of Investigation completes 60 years of existence, celebrating its diamond jubilee. It’s seen myriad highs and lows since then and has been the subject of multiple debates and discussions too.

Now is as good a time as any to contemplate why the CBI still hasn’t got all-India legislation – and why this needs to happen at once.

The CBI was born on April 1, 1963, deriving its legal status from the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act of 1946. It was formed as a central police agency to investigate corruption by public servants, breach of central fiscal laws, economic fraud, and special crimes of serious nature including terrorism. Its jurisdiction was extended to various states by a union cabinet resolution with the consent of state governments.

The CBI comprises of reputed police professionals, but there are issues that hamper its independent functioning, since it is entirely dependent on the government of India and the governments of various states for its day-to-day functioning. While it’s true that the CBI is an investigating agency that operates under the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure, and that it is answerable only to the courts, the agency is still at the receiving end of some uncertainty.

The CBI is merely an attached office of the ministry of personnel and administrative reforms. It requires administrative and financial approval from the central government for a number of matters. Its timing in certain matters is sometimes deemed questionable. People still say political alliances are made or marred depending on the CBI’s speedy or slowed-down investigations.

Importantly, the CBI has enjoyed a love-hate relationship with politicians since its inception. There are always clamours for a CBI probe – a politician facing and criticising a CBI probe in one case will demand it in other cases. It’s also often attacked as tool of the party in power, wielded to harass or intimidate political opponents. There have even been allegations that the CBI deals differently with people in power or those close to power centres, and that its conduct is not equitable.

Yet the CBI enjoys a reputation for its professionalism, competence and fair play. Multiple entities – government, judiciary, media, public – repose their faith in it. So, why hasn’t the CBI got all-India jurisdiction so far – something both the National Investigation Agency and the Enforcement Directorate possess?

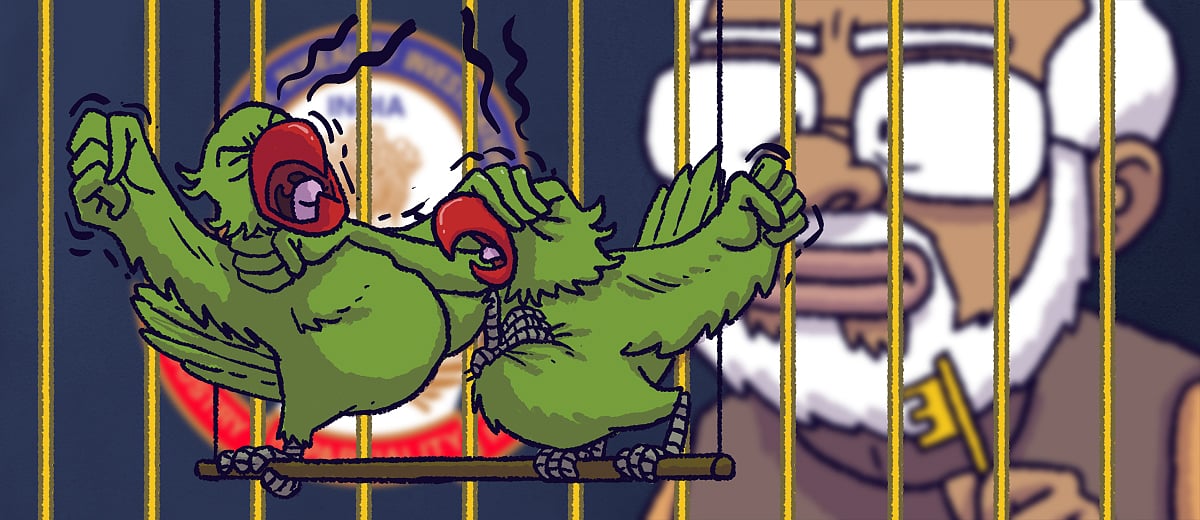

Instead, the CBI lacks statutory authority to investigate corruption and other cases, even against central government employees, throughout the territory of India. It’s dependent on the mercy of state governments to get – or be denied – consent to investigate cases under the Indian Penal Code, the Prevention of Corruption Act, and other special laws.

States have often abruptly withdrawn consent too, putting on hold CBI operations in that state. As things currently stand, mostly opposition-governed states – such as Chhattisgarh, Kerala, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Punjab, Rajasthan and Telangana – have withdrawn general consent given to the CBI, thereby denying permission to operate in these states.

Over the decades, bills have been introduced, discussed and debated in Parliament to rectify this sorry state of affairs. But an all-India statute could not be passed. This is also because many states, particularly opposition-governed ones, believe it’s against India’s federal structure. Law and order (including investigation) is a state subject.

Not many people know the CBI in 2013 was declared an organisation without legal sanctity by the Gauhati High Court. The Supreme Court later stayed this order, which essentially means the CBI operates under a stay order.

The NDA is in power at the centre with a sound majority, and it also governs a majority of states. Now is therefore the best time to pass legislation giving the CBI all-India jurisdiction, at least in cases of corruption involving public servants. Such legislation will be in public interest, because the bureau has great potential to work as an independent, impartial agency. Central and state governments must insulate the CBI from their influence, to allow it to flourish as an independent and autonomous entity.

Only then can the next 60 years of the CBI be a success.

SM Khan is vice president of the India Islamic Cultural Centre, New Delhi, former press secretary to the President of India, and former spokesperson of the CBI from 1989 to 2002.

#CBIvsCBI: It’s clear who Modi is backing in the Verma-Asthana feud

#CBIvsCBI: It’s clear who Modi is backing in the Verma-Asthana feudNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.