As Modi’s visit looms, tracing the missed warnings that set Manipur on fire

What the police records, eyewitness accounts, and conflicting versions tell us.

This report was first published on September 15, 2023. The headline has been updated amid reports that the PM is likely to visit Manipur this month.

Before Manipur transformed into a jumble of feuding ethnic zones with streets-on-fire sequences, there had been an eerie calm over its hills and its valley, sheathing undulating anger.

The Biren Singh government had ostensibly failed to see the warning signs – signs that were too clear in the last week of April. Even when the venue of a sports complex, which was set to be inaugurated by Chief Minister Singh in Churachandpur, was attacked by angry protesters from the Kuki community on two consecutive days.

Manipur, after all, had been simmering for years.

Sections of the Kuki community had seen the BJP government’s forest eviction drive as a bid to target them, and there was anxiety about a fresh court order suggesting that the Meitei demand for ST status – a longstanding flashpoint between tribals and the majority community – be considered. Trouble had been brewing since 2015, when the erstwhile state government, also headed by a Meitei, cleared three laws that were seen as pro-Meitei.

What did not help was also incumbent CM Singh’s anti-tribal image, bolstered by several remarks about “outsiders” – which some saw as a dog whistle for Kukis.

So tensions ran high when a Kuki BJP MLA invited the CM to the inaugural event in Churachandpur on April 27. Protesters first set fire to a gym that was part of the sports complex which was to be inaugurated. Demonstrators vandalised the venue again the next day, hours after the Indigenous Tribal Leaders Forum – a tribal umbrella outfit led by Kuki leaders – called for a shutdown in the district.

The authorities then suspended internet services and prohibited unlawful assemblies for five days in the district.

But on the day the curbs were lifted, the All Tribal Students Union of Manipur announced a solidarity march to protest the demand for ST status to Meiteis. And the violence that was unleashed on this day sent law and order and social harmony into a downward spiral, with Meiteis attacking Kukis in the valley areas dominated by them, and Kukis targeting Meiteis in the hill areas where they had higher numbers.

Normalcy is far. Just earlier this month, around 50 people were injured and two were killed in gunbattles in Tengnoupal and Kakching districts.

While the government has told the Supreme Court that no community is solely responsible for the series of events, Kukis and Meiteis continue to blame each other.

In first three days, 61 Kukis among 69 dead

Kuki groups say the violence began when Meitei miscreants burnt down the Anglo-Kuki war centenary gate around 2.30 pm in Leisang village in Churachandpur, but a series of FIRs seen by Newslaundry dispute the claim.

According to complaints filed by the state forest department, miscreants had vandalised a beat office around 11 am, targeting eight other forest department offices by the end of the day. Police officials claimed that the miscreants who targeted these forest offices in Churachandpur district were from the Kuki community.

The violence subsequently spread out to 1o districts, including Kuki-dominated Kangpokpi and Tengnoupal, and the Meitei-dominated valley districts of Bishnupur and Imphal East and Imphal West. It then branched out to Thoubal, Kakching, Chandel and Kamjong, according to the Manipur government’s status report.

On May 4, Manipur governor Anusuiya Uikey authorised all district magistrates to issue shoot-at-sight orders, but the violence continues – in the latest incident, a sub-inspector was shot dead in Churachandpur this week.

As per official data, 187 people have been killed across the state until August 5, including 118 Kukis, 64 Meiteis, one Naga, one Nepali, two personnel of the Central Armed Police Forces, and one unidentified person.

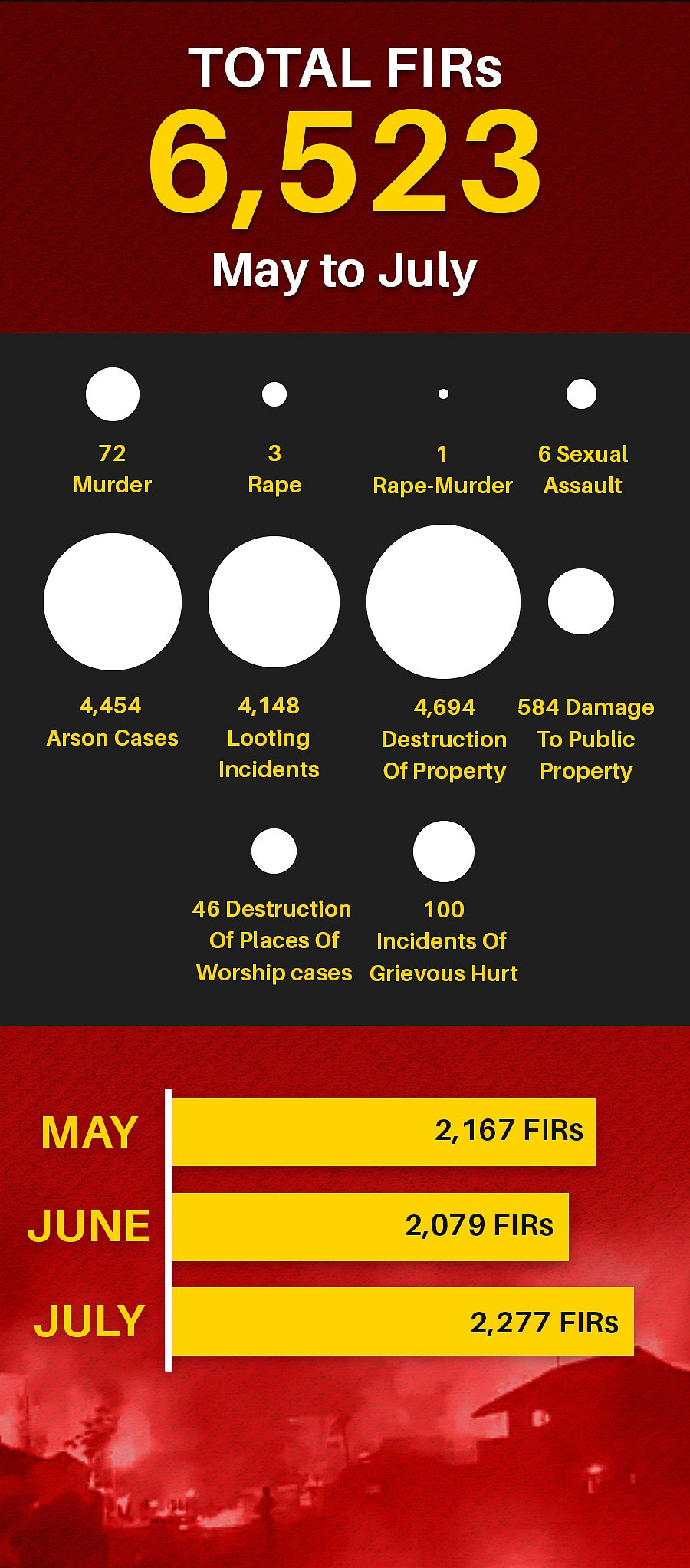

According to the state government’s affidavit, there had been 4,454 reported incidents of arsoning with 6,523 total FIRs lodged until July 31. The affidavit also mentioned 4,148 incidents of looting, 4,694 of destruction of house property, 584 of damage to public property, 46 of destruction of religious places and 100 incidents of causing grievous hurt. It also mentioned 72 murders, three rapes, one rape and murder, and six incidents of molestation.

As per police records until June, more than 4,000 weapons had been looted from state armouries, with the highest number of such incidents reported from the valley.

The highest number of casualties took place in the first three days. Between May 3 and May 5, 69 people were killed across the state, including 61 Kukis. But from May 6, the daily toll saw a dip. And by the end of May, there was a slight change in the pattern. Between May 22 and May 28, 23 people were killed, including 15 Meiteis.

There was also a surge in violent incidents in May, from arson to loot and murders, but this showed a downward trend in subsequent days.

So which districts suffered the brunt of the violence? How many men, women and children were killed? Who were the culprits? What about the role played by the police and support groups? Newslaundry sifted through police records and spoke to police officials, journalists and relatives of victims from both sides to understand the chain of events.

The first casualty on May 3

On May 3, the first casualty was reported in Churachandpur, and by the end of the day, about 19 were dead, including 18 from the Kuki-Zo community.

“I don’t have the courage to see the video of the lynching of my husband. I know he is dead and his body is in the hospital in Imphal. I cannot go there because the valley is dominated by Meiteis. It’s been more than 90 days…His body might be decomposed by now. I only want to perform his last rites and give him a respectful burial,” said 29-year-old Ningpi Kipgen, whose husband Sehkokhao Haopu Kipgen was the first one to die as violence broke out in Churachandpur on May 3.

It had come hours after the ATSUM’s tribal solidarity march – from the Lamka Public Ground to Peace Ground at Toibung – in Churachandpur in the morning. Ningpi and Sehkokhao were preparing to eat lunch at their K Phaijang village home after participating in the rally. But Sehkokhao put his meal on a plate, and left the house to eat with other villagers, moments before a Meitei crowd began assembling near the village, according to Ningpi. As she saw other villagers flee their home, she telephoned her husband. “He asked me to leave the village and to take my mother-in-law along. That was my last conversation with him.”

Since May 3, Ningpi has been living in K Salbung relief camp on a church’s premises in the district.

But while Ningpi was fleeing her village to save her family, 30-year-old Shanti Bala was waiting for her husband Ningthoujam Dijen Singh to get her paan, around 54 km away in Moirangkampu Mayai Leikai area of Imphal. Dijen, who was a construction contractor, was the first Meitei to be killed in mob violence that night. He was shot five times in Khongsai Veng in Imphal East.

“I didn’t realise that it was 10.30 pm and again called my husband. An unknown person picked up the phone and said that my husband is critical and asked me to come to Raj Medicity hospital…The doctor informed me that he was dead,” said Shanti, who now works as a daily wager to take care of her 10-year-old son Jelish and three-year-old daughter Changkhonbi.

How violence began, and trickled down

Kuki groups say the violence began when Meitei miscreants burnt down the Anglo-Kuki war centenary gate around 2.30 pm in Leisang village in Churachandpur, but a series of FIRs dispute the claim. According to complaints filed by the state forest department and police documents seen by Newslaundry, miscreants had vandalised a beat office around 10.30 am – before even the ATSUM rally began – targeting eight other forest department offices by the end of the day.

As per FIRs seen by Newslaundry, a forest beat office was vandalised at Bungmaul at 10.30 am, the second incident took place at 12.30 pm at Mata Mualtam village, the third at 1.30 pm at Saikot village, the fourth at Muallum village at 5 pm, the fifth at Kotlian village at 6 pm, the sixth at Singngat mission at 7 pm, the seventh at Henglep-Tuilimjang at 7 pm, another at Bijang village at 9 pm and the ninth forest beat office was burnt in Muizol at 9.35 pm.

After 3 pm, clashes erupted between the Meitei and Kuki community at Torbung Bangla and Kangvai on the edge of Churachandpur and Bishnupur districts.

A senior police officer said, “I was going to Torbung Bangla as reports were coming in that houses owned by Meiteis had been torched. While crossing through Nambol in Bishnupur, I saw a mob marching in the direction of Churachandpur. When I questioned them, they said they were going to Torbung as Kukis were torching houses of Meitei villagers. They were very angry and violent. The crowd was so violent that they were trying to climb the police vehicles. DGP Doungel also came to Torbung. The situation was so bad that we feared for his security and we had to evacuate him from there.”

By the evening, the violence had reached state capital Imphal, with rumours of a Meitei nurse being raped and murdered by Kukis.

And of the 18 deaths that were reported on May 3, the highest were from Meitei-dominated Imphal.

Police reports, however, try to present a picture contradictory to the numbers. According to a police report, Churachandpur district was the “epicentre of the volcanic law and order situation”.

“As an impulsive reaction, violent mobs surfed the valley districts from the tragic day and from the evening onwards, there was communal violence in the form of violent mobs of the Meitei community targeting the Zou-Kuki community in retaliation in some valley areas. Hence, similar crimes of killing Zou-Kukis, burning of houses or properties and displacement of Zou-Kuki people took place in some valley areas,” the report said.

Internet services were suspended and an indefinite curfew imposed in the valley districts on May 3. But it did not stop a mob from targeting Kuki students on the Manipur University campus the same night. They were rescued by the Assam Rifles, which is seen as a pro-Kuki force by sections of the Meitei community.

Of the 18 deaths that were reported on May 3, the highest were from Imphal. Police reports, however, try to present a picture contradictory to the numbers. According to a police report, Churachandpur district was the “epicentre of the volcanic law and order situation”.

May 4 with the bloodiest tally

There were 35 deaths on May 4, including 33 from the Kuki-Zo community. There were 24 deaths in Imphal and three in Churachandpur. Two Meiteis were killed – one each in Thoubal and Bishnupur.

A police inspector in Imphal West said that Imphal saw the worst violence on May 4 and May 5. “My phone was ringing continuously,” he said, adding that police evacuated 600 people to safe areas on May 4. Mobs went on a rampage in New Lumblane, Lamphel, Palace Compound, Trinity Theological College, Bazar India, Vishal Megamart, Checkon, and even targeted then DGP P Doungel’s residence.

“At around 4.30 pm, a mob of more than 2,000 men looted weapons from the camp of the Ninth Mahila Indian Reserve Battalion.At around 4.50 pm, I came to know that a mother and her two daughters were killed by the mob near NG college. On the same day, a mob of more than 3,000 people looted the armoury at the Manipur Police training college at Pangei.”

A journalist covering the violence said the violence could have been controlled with a 35,000-strong police force, the IRB, and the Manipur Rifles, asking how a mob could have overpowered police trainees while trying to loot armouries. “It seems the violence remained unchecked in the initial days. Organisations like Arambai Tenggol and Meitei Leepun were given a free hand in carrying out the violence. They were leading the mobs.”

The journalist claimed the two radical Meitei groups had a list of areas which had Kuki homes, and were “instigating the mob” to carry out attacks.

“Kukis started arsoning in Churachandpur and burnt Meitei houses in Torbung, after which Meiteis also started arsoning Kuki areas. The situation was chaotic on May 3 but it was still not out of control. But then the internet was suspended and rumours about a Meitei nurse being raped started doing the rounds. In retaliation to that, Meitei mobs led sexual assaults against Kuki women.”

On May 5, 15 people were killed, including 10 Kukis. Imphal saw four deaths while Churachandpur recorded 10.

Three Kukis were shot dead when a Kuki mob tried to stop the Army from evacuating Meiteis from Churachandpur. At least four others from the community were killed in clashes.

Meanwhile, three Meitei labourers, who were trying to return home to Imphal from Churachandpur, were abducted and killed, with their bodies eventually found between Chonchin and Saihum villages in Churachandpur.

The days after and police response

On the police role, an IPS officer posted in Imphal said, “Yes, there are many allegations against the police for not controlling the mob. But if police had not played its role, the death count would have been much higher…Violence started at Churachandpur, Moreh, Kangpokpi, Imphal and Bishnupur. At that time, the police force was the first responder. Large scale violence happened against Kukis in Imphal on May 4 and May 5.”

The officer said the mobilisation of groups such as Arambai Tenggol and Meitei Leepun cannot be denied but “it happened later”.

“Police force was there on the ground but multiple incidents were happening simultaneously because of which our teams could not reach all the places. Kukis were being attacked everywhere except in some areas of New Lumblane where Meitei neighbourhoods protected them.”

The officer also said that a large number of police was on bandobast duty with the vice president’s Imphal visit on May 3. “It was very challenging for us because we were unprepared for this scale of violence. We had handled a lot of violence in the past. But this was ethnic violence. In our department, there are personnel from both communities. Separation on ethnic lines did happen within the force as well, but fortunately there was no conflict between the police personnel…It was not an easy task because the mob was in thousands and they were in many pockets of the Imphal district.”

The bunkers come up

Nearly a week after police weapons were first looted, gunfights began along the border villages of Churachandpur and Meitei-dominated Bishnupur, as well as the adjoining villages of Kuki-populated Kangpokpi and Imphal, said the journalist.

And while the number of fatalities saw a dip after May 5, violence continued in the form of assaults and vandalism. By the end of the fourth week, the tables seemed to have turned, with geographic boundaries mapped out, the villagers armed, and more Meitei deaths as compared to Kukis – in the fourth week of the violence, there were 23 deaths, including 15 Meiteis.

According to the Manipur government’s status report, miscreants from both sides had subsequently set up 241 makeshift bunkers in nine districts – Imphal East, Imphal West, Bishnupur, Churachandpur, Kangpokpi, Kakching, Jiribum, Chandel and Tamenglong.

While the Biren Singh government claims it has removed all such bunkers, Newslaundry found several of them being used by fighters in Manipur.

While “village volunteers” claim before the media that they only possess single- or double-barrel guns, Newslaundry found them in possession of sophisticated weapons such as AK-47, Insas, M-16, and Sniper guns.

Months on, even the police are now part of many of these gunfights, with an increased presence of underground groups.

A senior police officer said, “After three months of violence, the situation has become more alarming within the police force, because police personnel from both sides have started taking part in gunfights. Many underground groups from both sides are taking part in violence.This situation is exploited by militant and insurgent groups…we have received intelligence reports about children being lured by militant groups as new recruits.”

On August 3, another mob looted the armoury of the Second India Reserve Battalion in Meitei-dominated Bishnupur.

The most barbaric killings

The ongoing violence has seen unspeakable barbarism, including bodies being mutilated, and shot repeatedly until the head was splattered open. Newslaundry spoke to the families, relatives, and acquaintances of the victims.

On July 2, David Theik, a 31-year-old from the Hmar Kuki subtribe who was guarding the Langza village of Churachandpur, was caught by a mob. Very few villagers had decided to stay back in Langza, which had a mixed population comprising the Kuki, Meitei, Kom and Bengali communities, after May 3. And when the attack took place in the early hours of July 2, everyone managed to escape, except David.

Muonpai Hmar, one of David’s friends who was on guard duty with him, said, “The attack took place in our village somewhere around 4.30 am. Hundreds of them came in vehicles and were armed. I managed to hide in the village. I was in hiding for almost three hours. They got hold of David…They first beat him up and then started mutilating him. I could hear his cries. They first chopped his hands, then legs and then beheaded him. After three hours, when I came out of hiding, I saw his head on a bush and the remaining parts of his body burnt down.”

David had been raised by his uncle, Buon Kholien, who is 72 years old. “David’s mother died at the age of seven and as my brother was physically challenged, I took care of David. In 2013, he left Manipur and went to work in Mumbai as well as Delhi. In 2020, he returned due to Covid and had been here since then.”

On July 5, two families were shocked by videos of the brutal killings of their two sons, who had gone missing on July 4. Irengbam Chingkheinganba, a 25-year-old civil services aspirant, had left for his sister’s house in Imphal’s Leikinthabi near the Kangpokpi border, with his friend Sagolsam Nganliba – both of them residents of Bishnupur.

One video showed Irengbam purportedly sitting on the ground, blindfolded, shot point blank on the back of the head, and then kicked into a pit. Another showed Sagolsam being killed in similar fashion.

Irengbam’s father Dhana Meitei, who lives in Bishnupur’s Sekmaijin Khunou village, said he got a call from one of his son’s friends on July 5 about the video. “He was not sure about it. He asked me to go to a place where I could access the internet so that he could send me the video. When I saw the video, it was my son’s. It was the video of his murder.”

“I filed a complaint at Sengmai police station. The last location of my son’s phone was traced to Gangviphai in Kangpokpi. I also wrote a memorandum to the chief minister but nothing happened. We haven’t received his body. There is an age-old tradition in Manipur. If we can’t find the body of a person, we perform the last rites using a Pangong tree. The tree is considered as the body of the deceased…His mother has given up on everything. She doesn’t eat properly, she doesn’t sleep. She just cries all the time.”

On July 15, Lucy Marim, a 55-year-old Maring Naga resident of Imphal, was kidnapped from Sawong-bung. A video of her murder was posted on social media, which purportedly showed around 20 gunshots being fired on her body until her head split open. “There is no head. It’s a nice way to kill,” shouted the attackers.

Among the nine suspects arrested in the case were five Meira Paibis – known as the “mothers of Manipur”.

Teenagers, including daily wagers and students, were not spared either.

Around noon on May 4, 18-year-old Paulalmuan, along with another teenager and a father of four children, was allegedly lynched by a mob at Keisanthong in Imphal, according to his uncle. All three were daily wagers. The teenager survived the attack. The bodies of the other two are still at the mortuary of the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences in Imphal.

On the same day, Letminching Haokip, 18, was trying to escape after a Meitei friend called him, saying he should escape, said his uncle Dalsianmung Chongloi. Letminching had moved to Imphal barely two months before the conflict, and did odd jobs. Official record shows that he was killed on May 4. “Since then, we don’t know under what circumstances he was killed. There are no eyewitnesses. His body is in the RIMS morgue,” said his uncle Dalsianmung Chongloi.

Letminching is survived by his wife and two children. His elder brother Letminthang, who worked in a chicken shop in Imphal, has been missing – it’s not clear if the brothers were attacked at the same time.

Death on video

There were many who came to learn of the death of their near ones through videos.

Consider the example of Lunginlal Haokip, a 35-year-old construction worker who was lynched in Imphal on May 4.

His wife Ichan Naokin, a Meitei, came to know of his death after a video purportedly showing three being beaten to death. “My husband used to live in Imphal and we used to live here in Churachandpur…When violence started on May 3, his employer hid him at his house…But then on May 4, he was beaten to death by a mob who threw away his body on the road.”

“I have seven children and I have to take care of them. Kuki social outfits are providing us food…but for how long can they help us? I need to start working, but in these turbulent times, there is no work anywhere.”

An endless wait for last rites

For several families, the wait to perform the last rites has turned to be endless.

“In Meiteis, we have a tradition that the body should first come home and then the last rites are performed…His body is still there in Churachandpur. I have given an application to the governor…I don’t know when it will come, but I am waiting,” said Ranjita Soibum, the 38-year-old wife of Soibom Othelo Singh – a road roller driver who was allegedly kidnapped and killed by Kuki militants while he trying to return to his home in Imphal on May 5.

Ranjita was informed of the death by the police on May 13. “They found his body along with two others near a hill stream. I met my husband in April. I never knew that it was our last meeting. My son keeps asking me about him…I told him that he is busy with work and will be back soon.”

Ranjita has started weaving shawls to make ends meet.

Meanwhile, in Churachandpur district’s B Phaicham village, Jamkhothang is waiting to resume duties as an Indo-Tibetan Border Police personnel – he was on poll duty in Karnataka when his 23-year-old brother Alex was killed during a clash on May 3. “We came to know that he was killed in firing. I was on election duty in Karnataka at that time. When I came to know about his death, I went to my unit and took leave for two months. I have extended my leave and will not go until I bury my brother respectfully. I can’t leave my family and community in this situation.”

Newslaundry had earlier reported on the families of two teens who were suspectedly abducted by Kuki miscreants, and whose families are still waiting for their bodies.

The women victims

The violence in Manipur has left 20 women dead – four of them Meiteis, according to data until July 31. A total of 10 cases of crimes against women were lodged across the state from May to July – the figure rose to 11 in August.

The impact of the conflict on women only became a prominent part of national headlines after a horrific video showed two women being paraded naked by a mob, drawing the attention of the PM, the Supreme Court and the National Commission for Women in July.

All these families are waiting for justice.

Consider the example of Florence Hangshing and Olivia Chongloi, two women from Kangpokpi’s H Khopibung village who worked at a car wash centre in Imphal East.

While the zero FIR has accused unidentified persons of their rape and murder, Olivia’s mother Kimkhohat alleged that members of the Arambai Tenggol and Meitei Leepun were behind the incident, which took place at the victims’ rented accommodation near Imphal’s Konung Mamang area on the evening of May 4.

The zero FIR, which was lodged after a complaint from Kimkhohat, was transferred from Kangpokpi to Imphal. “The concerned medical officer opined the nature of death was due to shock and haemorrhage resulting from multiple incised wounds and stab wounds to the body,” read the FIR.

Florence’s father Amos Hanshing said the owner of the car wash centre had told him on May 4 that he had dropped his daughter at the Manipur Rifles camp. “When we came to know about their deaths, I realised that he was lying…We are poor people and work as labourers.”

While many victims and tribal outfits have blamed the Arambai Tenggol, the outfit has maintained that it was disbanded in May and is now only being made a “scapegoat”. Weeks after student bodies demanded action against Arambai Tenggol and Meitei Leepun, the police booked Meitei Leepun chief Pramot Singh for allegedly promoting enmity.

***

As mobs targeted homes, escape was not easy for the elderly.

On May 4, 86-year-old Veinem Chongloi and her daughters Helam and Hekim were killed in Imphal’s Lamphel area, with three Meira Paibis present in their house. Veinem’s two sons had left their mother and sisters behind at home after the Meira Paibis suggested that no harm shall come to the women.

“Curfew was imposed. All five of us were sitting at home in Lamphel. We had locked the door from the inside…A few minutes later, three Meira Paibis knocked at the door. My elder brother, Thangkholal, opened the door. They entered our house…They asked us not to worry and said that they would make some arrangements to evacuate us…Then after a while, a mob wearing black T-shirts, with sticks and other weapons, broke into our house,” said Hemang Chongloi, Veinem’s 46-year-old son.

“We escaped through the backdoor and managed to reach the house of a close friend who was a Meitei. At his house, we came to know that the mob had killed an old woman and her two daughters…We realised that they were talking about our mother and two sisters.”

Three weeks after Veinem’s death, Kuki miscreants targeted Kakching’s Serou village in the early hours of May 28. And while the rest of her family managed to run and take shelter, Sorokhaibam Ibetombi, the 80-year-old wife of freedom fighter and former Indian National Army soldier Sorokhaibam Churachand Singh, was burnt alive in her home.

“We tried to enter the village but couldn’t amid continuous firing. From a distance, we saw our house in flames. And in the morning, we discovered the charred body of my mother,” said her son S Iboncha Singh.

Government officials were not spared either.

Nor were those with disabilities.

On July 6, Donngaihching Hangzo, a 64-year-old intellectually disabled resident of Imphal’s Lamphel, was shot dead near a school in Kwakeithel by two miscreants.

“She was mentally challenged, so she didn’t leave the area when the evacuation was happening. She told us that she will not go anywhere. She said I will stay back and everything will be normal. On July 6, when she was roaming around in the area, she was shot dead from a close range by two persons who came on a scooter,” said Ropui Hangzo, her sister-in-law.

Some were killed in prayer, such as Domkhohai Haokip, who was shot dead while she was praying inside a church in the early hours of June 9 in Kangpokpi’s Khoken village, allegedly by Meitei miscreants.

Meanwhile, families with Kuki and Meitei members seem to be split open by a double-edged sword.

“I am afraid to go to both Kuki areas as well as Meitei areas. I fear that both the communities could kill me and my remaining family. Otherwise, despite being a Meitei, my wife wouldn’t have been killed in Imphal. I don’t know how long I have to live like this in the camp,” said Inaoton Singh whose wife Lydia Lorembam was killed on June 4, along with 42-year-old Meena Hangshing and seven-year-old Tonsing Hanshing, despite police presence.

Lydia was just escorting her friend Meena and her son Tonsing, who had been accidentally hit by a bullet splinter amid a Meitei-Kuki gunfight, to the hospital in an ambulance. Meena, a Meitei, was married to Joshua Hansing, a Kuki. And it was perhaps this that made the Meitei mob target the trio.

“I had faith that the mob would not harm them, as both the women were Meteis,” said Joshua, who lives in Kangpokpi, adding that his wife and son had only gone to Imphal for medical treatment.

While calls to scale up army deployment, or to impose President’s rule amid a divided bureaucracy and the lack of a political solution, have repeatedly pointed to the government’s alleged failures, the BJP in the Centre seems to back Singh.

BJP government under global glare

During the monsoon session, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi had said the situation could have been controlled within two days had more boots been on the ground.

What was the deployment like?

By the night of May 3, 55 columns of the Army and Assam Rifles were deployed in Imphal, Churachandpur and Kangpokpi. Five companies of the Rapid Action Force were also deployed on May 4. By mid-July, there were 165 columns of the Army and Assam Rifles personnel in the state. Also on the ground were 48 companies of BSF, 57 of the CRPF and four companies of the ITBP. In the first week of August, 10 additional CAPF companies comprising 900 personnel were deployed. And by mid-August, there were 125 companies of paramilitary forces BSF, CRPF, RAF, ITBP, and SSB in Manipur.

However, the state continues to be rocked by violence – whose genealogy can’t be traced without looking at the BJP’s response.

Despite the protests and violence, CM Biren Singh has refused to climb down from his resolute position on the issue of forest land, let alone engage with protesting organisations.

While calls to scale up army deployment, or to impose President’s rule amid a divided bureaucracy and the lack of a political solution, have repeatedly pointed to the government’s alleged failures, the BJP in the Centre seems to back Singh.

Speaking in Parliament last month, Union home minister Amit Shah had turned down the opposition’s demand to impose president’s rule in Manipur, saying the need would have arisen had the CM not cooperated.

The Manipur crisis has also drawn international condemnation.

In July, the European Parliament had passed a resolution asking the Indian government “to take all necessary measures and make the utmost effort to promptly halt the ongoing ethnic and religious violence”. It had also demanded an end to the internet shutdown and to grant unhindered access to the news media and international observers.

Earlier this month, when the special rapporteurs of the United Nations issued a press statement about the “serious human rights violations and abuses” in Manipur, including alleged acts of “sexual violence, extrajudicial killings, home destruction, forced displacement, torture and ill-treatment”, the Modi government had dismissed the remarks as “unwarranted, presumptive and misleading”.

But the deep disquiet and protests in Manipur continue to suggest otherwise. With thousands in relief camps, anguish persists over the Centre’s position; like the question posed by Sangarambam Mandalee, a student, at a demonstration in Imphal.

“You have avoided us…Are we not Indians?”