As COP28 debates phrasing on fossil fuels, a snapshot of life near India’s coal mines

India eventually agreed to ‘phase down’ – not ‘phase out’ – fossil fuel. But how will this impact residents of Medhauli?

The 197 countries and the European Union in attendance almost did not reach a consensus on the final statement at the 28th Conference of Parties – or COP28 – which ended on December 12 in the United Arab Emirates. Organised by the United Nations to build international consensus on how to tackle climate change, this was the first year that the conference planned to have a global stocktake to account for how far countries have progressed in achieving targets set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

There was confusion and surprise in the plenary and overflow rooms, as well as for participants attending virtually, when the COP28 president, Sultan Al Jaber, passed the global stocktake text in five minutes on December 13. This was almost 24 hours after proceedings had ended, without any room for further discussion. Island nations such as Samoa had planned to add their comments to the text, but never got a chance.

Importantly, negotiations had stalled after a tense faceoff between developing countries on whether to use the terms “fossil fuel phase out” or “fossil fuel phase down”. They also butted heads on climate finance and the role of historic emissions to keep to the scientific goal of 1.5 degrees.

The final UAE consensus said coal should be “phased down” and not “phased out”, which will allow countries like China and India to continue to expand their carbon emissions via coal. In August, India cut its rate of increase in carbon emissions by a third since 2014. But it remains the fourth largest emitter in the world and is silent on coal production, which continues to expand.

At the proceedings in Dubai, India reiterated its demand for common but differentiated responsibilities, which would give it more breathing room to continue on its high energy development trajectory. During the head of delegations meeting on December 11, both India and China opposed any text that was too prescriptive for developing countries while continuing to emphasise on the responsibility of historical emitters like the United States of America and Europe to keep the rise in global temperatures at 1.5 degrees above normal.

This rejection of the phasing out of fossil fuels is devastating, said a group of small island countries that are likely to disappear if global temperature increase is not capped at 1.5 degrees above normal and if sea levels continue to rise.

“I’ll be brief but I’ll speak from the heart,” said a Marshall Islands representative during a closed meeting of selected countries called Majlis or “council” on December 10. “Our national adaptation plan envisions that by 2040 if nothing is done then then the Marshall Islands will be forced to let go of some of our islands and relocate to other islands, abandoning their home, cultures, and the bones of their ancestors. The issues are clear here.”

India itself has been reeling from extreme weather events that have been linked to changing climatic patterns impact vulnerable groups the most.

Over the years, India’s position at succeeding COPs has evolved from a stance that sought more accountability from developed countries such as the US and those in the European Union, to one more aligned with the ‘like-minded developing countries’ bloc of parties in deferring the phase-out of fossil fuels and accountability to a later date.

This year, India built on its stand of “vasudhaiva kutumbakam” to build “one earth, one family and one future”, which it first emphasised when it hosted the G20 summit in Delhi this year.

“The way ahead must be based on equity and climate justice,” said Bhupender Yadav, minister of environment, forests and climate change at the closing plenary session on December 13. “Let us implement the Paris Agreement in letter and spirit through the global stocktake process.”

Dr Florentine Koppenborg, an observer to the negotiations from the Technical University of Munich, said, “It has been 31 years since the adoption of the UNFCCC Rio Conference and, for the first time, the international community agreed to include language on fossil fuels in a climate treaty. In that sense, the phrase ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’ is historic. The world has taken a first step towards moving beyond the fossil fuel age, but the adopted language is weak, which means many more steps are required.”

This is even as India continues to push for unabated expansion of coal production and use as it seeks to build its energy capacities: in 2023, Coal India Limited, India’s largest state-run coal producer, announced that it aimed to expand its production of thermal energy from 893 million tonnes in 2022-23 to 1 billion tonnes per year by 2024-25.

Phasing down coal

The final text of the COP28 agreement emphasises the need for “sustainable and just solutions to the climate crisis” that are founded on the “participation of all stakeholders”.

But India’s ambitions to expand coal come at grave cost to its own people.

On the morning of February 7, 2022, thousands of kilometres from Dubai, Ram Kumar Basor, then 17, returned from grazing his goats in Medhauli village in Madhya Pradesh. The teenager washed his hands and began to eat lunch in the compound of his home.

Suddenly, a massive explosion rocked the village. The wall against which Ram Kumar was sitting toppled, killing him on the spot.

The prescribed distance for a settlement from the blast area of a mine is 500 metres from the danger zone, according to Coal Mines Regulations, 2017. But Medhauli in Singrauli district is perched just 75 metres from the edge of an opencast coal mine run by state-owned Northern Coalfields Limited and around 10 km from the district headquarters in Waidhan.

It’s a precarious village where blasts to extract coal are a daily occurrence – to the point that locals avoid sitting in their houses every afternoon.

Over a year later in August 2023, Chhotak Basor cried silently as others around him recounted the events that led to his son’s death. Ram Kumar’s twin brother Lakshman stood aside, watching the scene quietly.

NCL gave Basor notice to break his house in 2011. All that was left, he said, was two rooms and two walls.

“On January 1, 2022, [NCL workers] broke the front wall of our house and were going to return to break the back wall,” Basor said. “But before that, our son died.”

Basor’s family received compensation of Rs 5 lakh from NCL for Ram Kumar’s death, but NCL has yet to pay them compensation for their house, which is set to be demolished, and it also has not assigned the family a new plot.

Medhauli was not always this close to the mine. Around 20 years ago, the village was in an area now long lost to NCL’s opencast mine, shifted as NCL expanded its mine to include the area beneath it. In 2003, NCL shifted Medhauli to its current location. Now in 2023, it has stepped up the process of shifting them once again – this time with no clarity on where they should go.

Cracks are visible in all the walls of houses in Medhauli. Residents live in terror of bricks and walls collapsing on their sleeping children. During the blast hours between 1 pm and 3 pm, residents shelter under nearby mahua and mango trees. The groundwater from their wells is now used for coal mining. Instead, NCL supplies residents with water tankers for drinking and domestic chores.

India’s transition from thermal to renewable energy will not come soon enough for people such as the Basor family who live near coal mines in India and have to deal with daily disruptions, pollution that causes long-term health issues, and even sudden death.

Climate justice

Singrauli is full of contradictions. Vast old forest lands overlook massive hills of overburden – soil and rock debris left over from digging up coal. People build their daily routines not around their work, but around the blast schedules of mines. In villages and towns alike, people live in uncertainty with the knowledge that at any time, the government can declare new coalfields open.

India’s position on coal internationally is similarly contradictory. India has followed China, Saudi Arabia, and the LMDCs on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. At the same time it has been difficult to track India’s specific stance on the phasing out of fossil fuels. It has remained largely silent on specifics or stood with countries such as China to push back against the “prescriptive” nature of the draft text on December 11 or to peak emissions by 2025.

“It is not that late runners are not willing [to reduce fossil fuels], it’s because they are hungry and have no shoes,” China said in a closed Majlis meeting on December 10. “We are a big family. So we need to help each other and provide finance, capacity building and technology.”

Dr Koppenborg noted, “The LMDCs had a large impact as they blocked mentioning any prescriptive policies or sectoral targets, which was a long way away from the concrete targets and phase-out language asked for by the high ambition coalition. By essentially blocking anything, they expanded the range of options and moved the landing zone for a potential compromise closer to their position.”

She added: “India was somewhat more quiet on the issue than two years ago in Glasgow where they rather forcefully insisted on their ‘right to a responsible use of coal’. This time, Saudi Arabia and China were very vocal.”

At the same meeting on behalf of the LMDCs, Bolivia emphasised climate justice instead.

“The goal to reach 1.5 is not a common goal for all and this is no longer differentiation [of developed and developing countries],” the South American country’s representative said. “Developing countries must achieve net zero at the same time as others.”

Pushing for climate finance from developed countries, Bolivia noted that countries that had peaked emissions over 150 years were now asking less-developed countries to achieve the same goals in just 10 years. “This is no justice,” Bolivia said.

The LMDCs strongly called out the developed world for their lack of commitment to climate finance and the twisting of the Paris Agreement to transfer responsibilities from the public sector to the private sector and to multilateral development banks. The LMDCs also called out developed countries for shifting their responsibilities leading to a lack of consensus on the term “phase out” of fossil fuels.

India’s position has been more of a silent observer than a leader at this COP.

Cost of expansion

For residents of Singrauli, these discussions hold little meaning. NCL keeps expanding and as Akhilesh Basor, a resident of Medhauli observed, “In Singrauli, NCL is the government.”

There is also a more literal cost to coal expansion. By most rehabilitation standards in India, NCL is generous to the people it displaces. According to the principles of climate justice, the people it displaces are compensated for their loss of land, livelihood and property. It gives new plots in different locations. It gives people money after they prove that they have demolished their houses.

But a closer look shows how reluctant the state-run organisation actually is to do this.

Akhilesh said NCL officials claimed plots to be acquired in Medhauli for the expanded coal mines under section nine in 2011. The Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act of 1957 requires state-run companies to provide compensation according to legal standards set by the centre. In 2013, the central government passed the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, which gave far more generous remuneration to stakeholders than the previous Land Acquisition Act.

In 2017, NCL verified its measurements of plots and property in Medhauli, but three years later revised them, saying that the plots were much smaller than they had measured – leading to people’s compensation being cut by 20 percent.

“We give up our lives for your luxury,” said Ram Naresh Basor, another resident of Medhauli.

The public relations officer of NCL at Singrauli said the process of verification was repeated as there were doubts about the veracity of the 2017 survey, adding that they found in the second verification that there were houses that did not exist on the list of beneficiaries. The 2020 survey was carried out with representatives of the people, local government and NCL officials.

”Whatever compensation was adjusted was calculated according to the Land Acquisition Act,” he said.

A management official at NCL, who declined to be named as they are not authorised to speak to the media, said: “If the nation needs it, then this work is necessary in the public interest. That too will happen as per the Coal Bearing (Areas) Act and the [Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act]. NCL is a responsible corporate citizen so whatever happens will happen as per the act and in the interest of people. We will take comprehensive consent for this.”

Lalai Basor, a resident of Medhauli sees it differently. “There is no contentment in the area of a mine. We all have to die anyway – but why do you have to kill us first?”

Mridula Chari is an independent journalist based in Mumbai. Denise Fernandes is a PhD researcher at University of Colorado-Boulder.

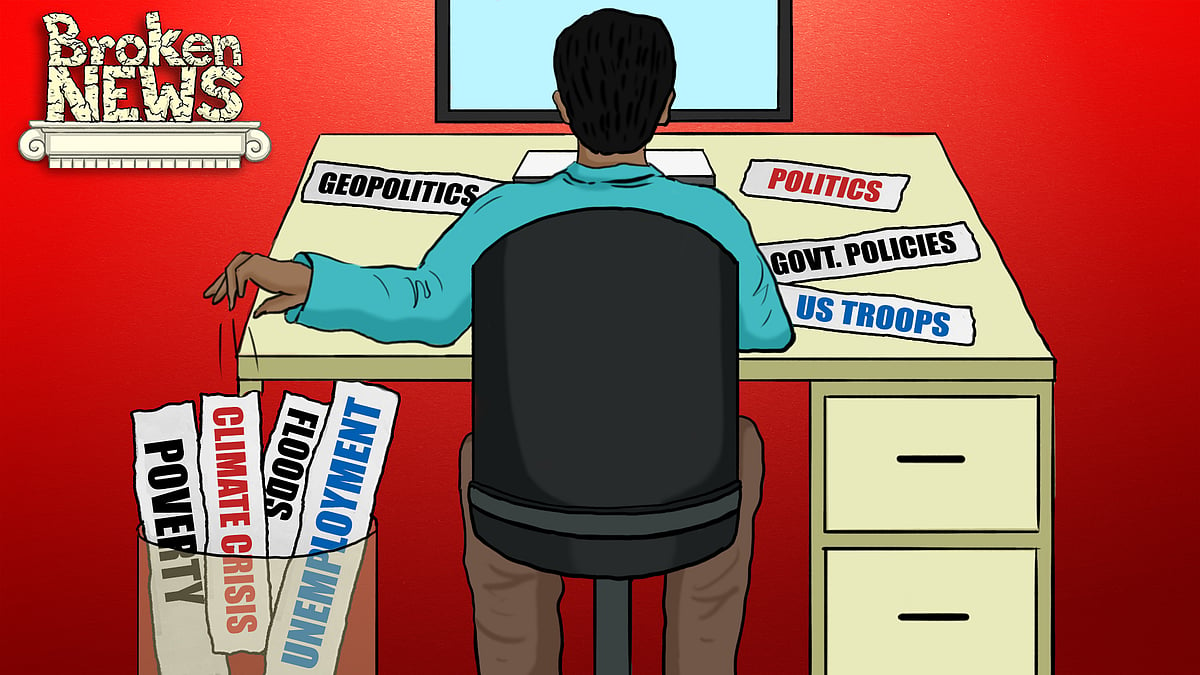

From climate change to healthcare: Why is there no space for these issues in Big Media?

From climate change to healthcare: Why is there no space for these issues in Big Media?