Ram Mandir: A tug at long civilisational memory, discounted by some

Without a wider historical register of Indian nationhood, the call for ‘constitutional patriotism’ seems shallow.

It isn’t surprising that a large section of the western commentariat is ill-equipped to grasp the exuberant and deep resonance of the Indian populace with the Ram Mandir inauguration in Ayodhya. The inability to do so is often a case of lack of frames; the blinkered view missing most of the landscape.

Similarly, it isn’t also new to see that such blind spots aren’t in short supply among a section of Indian opinion-makers. They have formulaically used the same frames. And in the process, they have got smug with the borrowed view. Behind a veil of sophistication, these Indians have been trying to conceal their lack of original tools to decipher events like the consecration of the Ram Lalla idol in Ayodhya. In essence, their bemusement is a crisis of inadequate frames and reveals the limits of borrowed tools.

Beneath the surface of immediacy, what are the ways in which such outpouring of people’s response can be read?

Can it be solely tied to the political realm and the power equations, even if they are important? These questions ask for a wider canvas to place any exercise in understanding how a significantly large number of Indians reacted to the event – with a sense of jubilation and traditional devotion.

One of the clearest ways of reflecting on such a response is viewing it as tugging at the strands of continuity in the long civilisational memory. In one form or the other, the resilient continuity makes it one of the very few persistent civilisational constructs in the world.

At the same time, the deep imprint of this long journey, which also had phases of brutal hardships, meant that without taking note of it, the modern claims of “constitutional patriotism” – to borrow German theorist Jurgen Habermas’s phrase – sounded contrived and even shallow. This was never going to be taken as ordinary neglect; the invocation of a national personality could not breathe in a vacuum.

It isn’t that the political leadership in the years preceding India’s independence, and the years following it, weren’t aware of the significance of this continuity.

The enduring nature of the “ancient palimpsest” symbolising India’s civilisation, as Jawaharlal Nehru wrote in The Discovery of India (1944), is such that “no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously”.

The conception of a sacred geography, as a marker of India’s nationhood, over thousands of years could be seen in how Mahatma Gandhi looked at ancient pilgrimage sites in his work Hind Swaraj (1909).

“What do you think could have been the intention of those far-seeing ancestors of ours who established Shvetbindu Rameshwar in the South, Juggernaut in the South-East, and Haridwar in the North as places of pilgrimage? You will admit they were no fools… they saw that India was one undivided land, so made by nature. They, therefore, argued that it must be one nation—and fired the people with an idea of nationality in a manner unknown to other parts of the world,” wrote Gandhi.

Even if it seemed tokenistic, it’s worth recalling that as early as the commencement of the constitution in 1950, the subtext of civilisational recollections can be seen.

The very first article of the Indian constitution reminds Indians of their land as “Bharat”, declaring, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a union of states.” It is important that the drafters used the ancient nomenclature of Bharat, not the more contemporary Hindustan. This could be seen as the need for identifying civilisational ancestry. However, that was little consolation for the accumulated grievances of a very long journey. Something important was still missing; the institutional forgetfulness about the brutal encounters with centuries of invasion and plunder was not healing the scars of the ages.

The painful episodes too, and the lack of sustained gaze on such brutalities was a case of obfuscation. The “succeeding layers” left some violent marks too, inflicted by acts of mediaeval vandalism against Hindu places of worship. The long period of insults and violence perpetrated against the native faith of this “wounded civilisation,” in VS Naipaul’s evocative phrase, was not to be seen in the state’s recollection of its past.

The attainment of independence from British rule in 1947, Naipaul observed, could not conceal the fact that India was a land of far deeper wounds suffered during the mediaeval plunder and conquests that turned it into a land of “far older defeat”. The amnesia in India about these painful episodes surprised him. Such historical grievances, however, had found few voices, both within a section of the Congress and in more organised ways, among Hindu organisations that emerged in the first half of the twentieth century.

In post-independence politics, the longer register of civilisational memory formed a key part of the ideological outlook of political parties like the Bharatiya Jan Sangh, the predecessor of the present-day Bharatiya Janata Party which filled in the space for articulation of Hindu interest.

The BJP looked back at history not only to invoke pride, but also reminded the community of the excesses of mediaeval vandalism and plunder.

Moreover, they argued that the painful part of this civilisational journey had been ignored by the hypocritical practice of secularism by the dominant Congress government, a smokescreen for minoritism and allied electoral benefits.

This critique also meant that the BJP was pitching itself in a space that was offering parity to the majority community to register their grievances, tapping into the community’s sense of historical injury.

The political push for seeking equality of space for the aggrieved Hindu interests had its own salience in a pluralistic democracy, where the party advocating the majority community’s cause was alleging the neglect of its concerns. Such callousness can sometimes be traced to the distortions in the working of pluralistic systems, which stray into the dubious morality of prioritising the interests of some groups to the exclusion of the concerns of the big groups.

In Britain, political thinker Roger Scruton, for instance, cautioned against the dangers of such an approach. He was of the view that, like all groups in a society, the majority “needs not only be not ignored, but it also needs to be respected”.

As this could be easily misunderstood, here, it’s important to note that he was asking for the majority to be “not ignored” and “respected,” only as much as other groups in society.

As the BJP and the Sangh Parivar groups started galvanising support for the Ayodhya Ram Mandir movement, it drew on the aggrieved part of the long civilisational memory.

Its political mobilisation in late 1980s was premised on breaking the lull of amnesia and state neglect and aimed at reclaiming one of the holiest sites of the ancient faith.

There were phases, when the movement got aggressive, even militant as some argue. In one such episode, the kar sevaks of the movement were dealt with state bullets, as government records show that at least 17 of them were killed in a police firing in October 1990.

Two years later, whether by design or accident, the movement took a militant turn on the day the disputed mosque was demolished by kar sevaks in December 1992 – a criminal act that saw inquiry and trial as a criminal case.

However, the litigation for rights over the place of worship proceeded as a civil suit and concluded with the landmark judgement of the Supreme Court in 2019.

The verdict, on the basis of the court’s evaluation of the evidence and arguments, ordered the land to be handed over to a trust for construction of the Ram temple. In essence, an episode of deep civilisational anguish sought redressal in the judicial court, and a sense of closure seemed to have come with a much delayed acknowledgment.

Even if the reclaiming of the site of the Ram temple was achieved through the judicial process and the verdict of the highest court of the country, the articulation of Hindu interests had gained a new vigour with the power consolidation of the BJP and its allied groups.

Since the early decades of the last century, the political groups that gave voice to Hindu interests were clear about the fact that the pursuit of political power was key to their chances of being heard in the mainstream of the country’s politics.

After Independence, it took almost four decades for these groups to emerge as significant political forces in different parts of the country. However, the limited electoral mandate and compulsions of coalition politics did not let the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led BJP resolutely explore the possibilities of articulating core themes of Hindu interest during its power stints at the centre.

In 2014, the clear electoral mandate for the party under the leadership of Narendra Modi, and its reinforcement in stronger mandate in 2019 opened new avenues for how the political Hindu could now view the civilisational memory in the public realm.

This remained an undercurrent of the new government at the centre, as well as its effect. “To understand the Modi regime, one has to accept that Modi was therapeutic for a generation that felt that elite modernisation was a hypocritical affair conducted by groups which used words like ‘secular’ to dismiss the thought processes rooted in religion and folklore...By articulating such anxieties, Modi soothed their wounded subconscious. And this ‘wounded class’, tired of pseudo secularism, elite cronyism and majoritarian hypocrisy, voted him to power,” wrote sociologist Shiv Visvanathan in 2014.

The response to the Ram Lalla idol consecration can be placed in the longer arc, or continuum, of civilisational memory of millions of believers in the country.

The fact that it intersected with the political forces that gave articulation to these interests and pursued power on their behalf was also a process that took decades in making in post-Independence politics.

This piece was published with AI assistance.

Ayodhya: Temple is inaugurated, ‘Balak Ram’ consecrated. What next?

Ayodhya: Temple is inaugurated, ‘Balak Ram’ consecrated. What next? Elaborate stages, live shows, saffron flags: Inside Big Media circus in Ayodhya

Elaborate stages, live shows, saffron flags: Inside Big Media circus in Ayodhya Modi’s ‘political triumph’, ‘old wounds’: Foreign media on Ayodhya inauguration

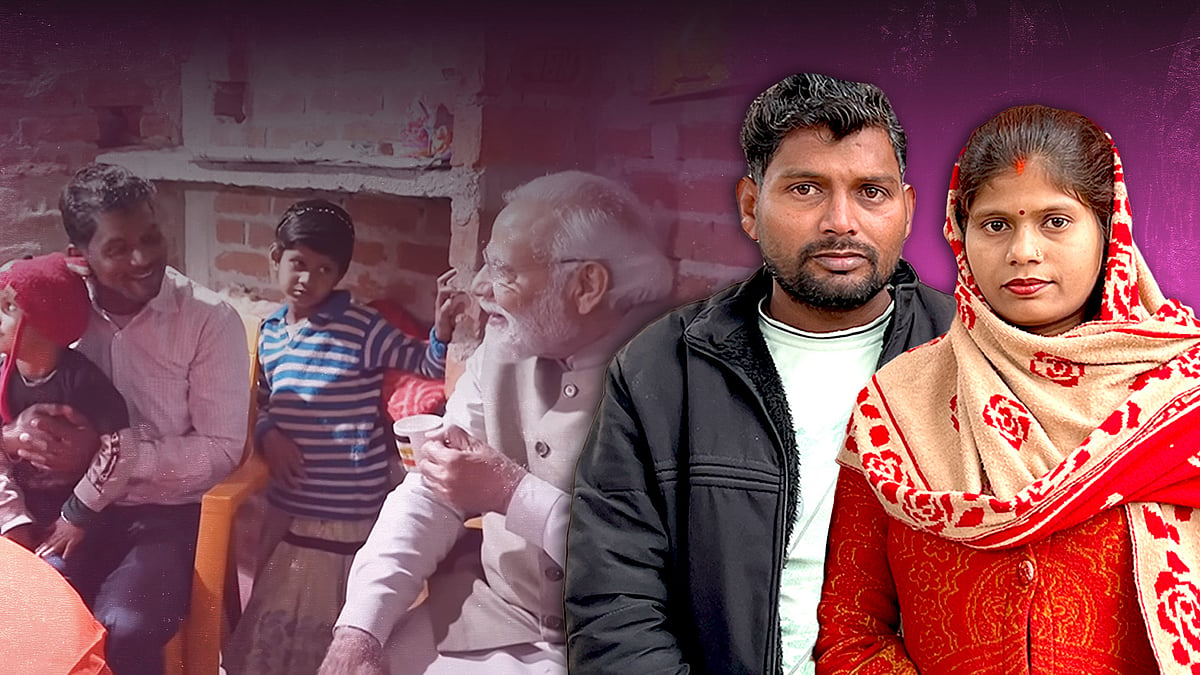

Modi’s ‘political triumph’, ‘old wounds’: Foreign media on Ayodhya inauguration ‘No toilet, drowning in debt,’ says Ayodhya Dalit woman who hosted Modi for tea

‘No toilet, drowning in debt,’ says Ayodhya Dalit woman who hosted Modi for tea