4 decades, hundreds of ‘custody deaths’, no murder conviction: The curious case of Maharashtra

Tracing the broken trail of justice in India’s deadliest state for custody deaths.

Read the previous installments of this series here.

Zarina Yelamati’s life changed forever on a rainy June night in 1993.

She was just 27 then, a young mother of two, asleep beside her husband in a modest railway quarter in Nagpur, when the police burst through the door. They claimed to be looking for a robbery suspect named Anthony. But when they didn’t find him, they turned on her husband, Joinus Adam Yelamati, a diesel mechanic who was once a suspect in an old case.

By morning, her husband was dead – tortured in custody. And she was thrust into a battle for justice that would consume half her life.

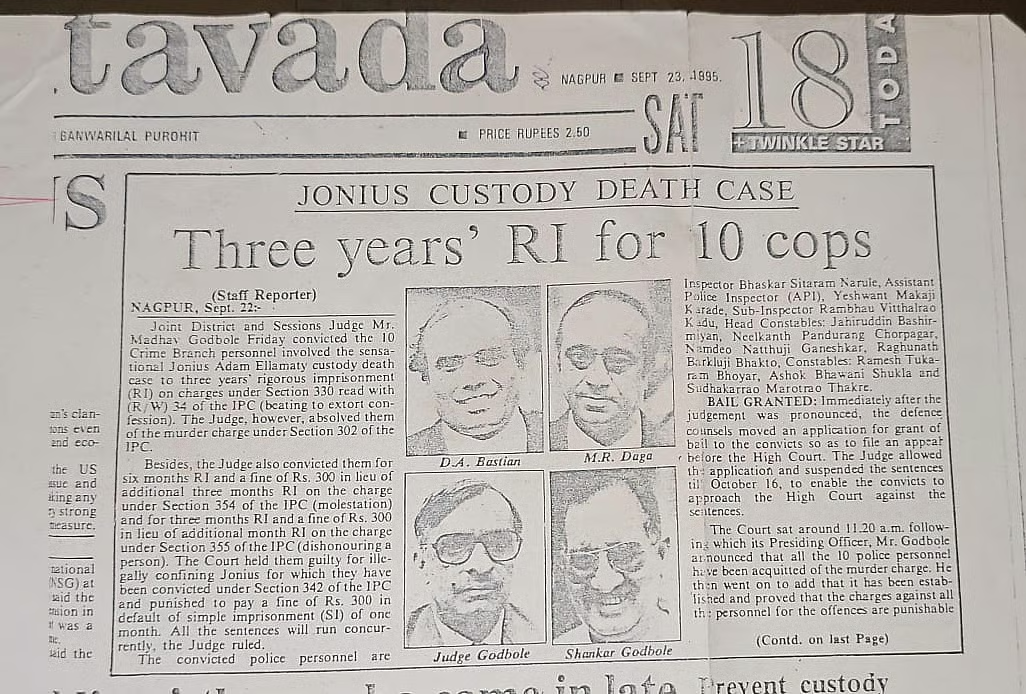

It took 25 long years and three different courts for the police officers who tortured Joinus to finally be convicted. Though they were not held guilty of murder, the Supreme Court, in September 2018, sentenced them to seven years of imprisonment.

It was a rare judgment. Considering that conviction rates in such cases across the country range from zero to one percent, according to Status of Policing in India Report 2025 which cited data from the National Crime Records Bureau and the National Human Rights Commission. (NHRC data on custodial deaths available on Dataful here.)

In fact, not much has changed in decades. In 1994, a study by the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy suggested that out of 415 custodial deaths recorded between 1985 and 1994 across India, only three had resulted in convictions.

The figures vary across sources but point to a singular trend around such cases in India, especially in Maharashtra.

In 2022, a Lok Sabha response by the Union Ministry of Home Affairs citing NHRC data pointed to 155 custodial deaths from January 2021 to February 2022, with disciplinary action in 21 cases but prosecution in none. Maharashtra topped the list, with 29 custodial deaths in 2021–22 alone, as per the ministry’s response in the Lok Sabha. As per the Status Of Policing in India Report 2025 too, Maharashtra has the highest number of cases of deaths and rapes in police custody registered before the NHRC, with an average of 21 cases every year from 1994 to 2022. Out of 404 custodial deaths in the state between 1999 and 2017, FIRs were filed only in 53 cases and chargesheets in only 38.

But long story short: there has not been a single conviction on murder charges in such cases in Maharashtra in at least the last four decades, as per information in the public domain.

And behind these statistics are families struggling for justice.

Nagpur: A rare conviction

Today, at 59, Zarina quietly goes about her duties as an attendant at the railway medical clinic in Nagpur. But behind her composed exterior lies the harrowing story of what happened in 1993 and the years that followed.

“My husband had returned from work and filled his duty register as usual,” Zarina recalled about the incident on June 24, 1993. “We were all sleeping – our children were just eight and nine years old – when the police kicked down our door. They didn’t ask questions. They just started beating him.”

The policemen ransacked the house, she said, and under the pretext of a search, molested her. “They dragged my husband out, tied him to an electric pole, and kept hitting him with lathis. My children were terrified. I tried to hold them close, protect them – but we were all terrified.”

The family was bundled into a police van. The assault didn’t stop. “Inside the van, they kept touching me. At the Crime Branch office…they dragged Joinus into a room and stripped him naked. Ten minutes later, they called me in. He was still naked. One officer hit me and then tried to put his hand inside my saree and mocked me – ‘Give me your nicker, I’ll make your husband wear it.’ I still haven’t forgotten that night,” she said.

Later that night, they were taken to a hotel. While Zarina and the children waited in the van, Joinus was taken inside. When he returned, he was barely conscious. He was thrown into a lockup at Rani Kothi, without any charges being filed. By morning, he was dead.

“I didn’t even know he had died until the next day,” Zarina said, adding that her husband was a tuberculosis patient. “They kept beating him all night…he was a railway employee. Every day, he reported for duty and signed the attendance register. The police could have checked that register and confirmed he was at work, not out committing a crime. But they didn’t bother.”

“An FIR was filed at Sadar police station. But that was just the beginning. For a year, my relatives collected donations for me from the church so that I could feed my children. I was 27, widowed, with two children. I got a job as a sweeper in the railways, because Joinus was a railway employee. I did that job for 18 years and fought the case.”

But the battle went beyond the courtroom. “One day, some men came to my house and threatened me. Told me not to testify…I told my lawyer, D Bastian…I got police protection.”

The pressure didn’t end there. “The cops even tried to buy me off. Offered me Rs 25–30 lakh. I said I’d rather die than take money from them,” she claimed.

In the trial court, the policemen were given just three years. Zarina didn’t give up. She went to the High Court, and then the Supreme Court. “I wasn’t even given compensation,” she said. “But I knew I had to keep going.” In 2018, the Supreme Court sentenced them to seven years in prison. “Half my life went into this battle. But at least they went to jail. That gives me some peace.”

In the trial court, the policemen were given just three years. Zarina didn’t give up. She went to the High Court, and then the Supreme Court. “I wasn’t even given compensation,” she said. “But I knew I had to keep going.”

In 2018, the Supreme Court sentenced them to seven years in prison.

“Half my life went into this battle. But at least they went to jail. That gives me some peace.”

Mumbai: Stuck in procedure

In Mumbai, 64-year-old Leonard Valdaris continues his daily pilgrimage to St Joseph’s Church in Wadala. Every morning, he spends two quiet hours in prayer before picking up breakfast for his elderly mother. Every evening, he returns, seeking the peace that continues to elude him. “Sitting in the church gives me some peace and hope, though I am losing both with every passing day,” he said.

For the last 11 years, Leonard has been fighting for justice for his son Agnelo Valdaris, who was allegedly tortured and killed in police custody. Despite a Supreme Court order, the trial hasn’t even begun.

On April 15, 2014, Government Railway Police sleuths arrived at Leonard’s house, asking about his son while hunting for suspected chain-snatchers. He took them to his parents’ home in Dharavi where 25-year-old Agnelo was staying that night.

“The moment we entered the house, policemen pounced on him and started beating him,” Leonard claimed. “They only stopped when I told them I would complain to higher authorities.”

Leonard claimed it was “the last time” he saw his son in “a normal state of health”. Agnelo and three friends, including a 15-year-old minor, were taken to Wadala GRP police station where they allegedly endured eight to nine hours of torture.

They were all allegedly stripped naked, beaten with grinder belts, and hanged upside down. One of Agnelo’s friends was allegedly forced to perform sexual acts on him and the minor. While the three others were eventually taken to hospital on April 16, Agnelo was allegedly tortured more at the station.

On April 17, when Agnelo wasn’t produced in court, Leonard raised the issue with the magistrate, who ordered police to present him. When the police didn’t comply, Leonard took the court order directly to Wadala GRP police station, where officers claimed Agnelo had been taken to Sion Hospital for “minor bandaging”.

“I rushed to the hospital and the moment my son saw me, he broke down crying, begging me to save him,” Leonard claimed. “That image of his tearful, terrified face still haunts me. He was a strong, loving boy, but he was covered in injuries and couldn’t even walk.”

Leonard alleged that he was forced to sign a statement claiming his son’s injuries were self-inflicted. They threatened not to produce Agnelo in court unless he complied.

“Agnelo repeatedly told me not to write or sign anything, but I was concerned for my son’s life and wrote what the police demanded,” Leonard claimed.

That night at 8.30 pm, Agnelo was discharged from the hospital. It was the last time Leonard would see his son alive.

The next day, when police again failed to produce Agnelo in court, Leonard’s inquiries led to a devastating revelation: police claimed Agnelo had tried to escape custody and died by suicide, jumping in front of a train.

Despite filing an FIR on April 30, 2014, and securing a CBI investigation that alleged evidence tampering by police officials, the case has been mired in procedural delays.

The CBI chargesheeted eight officers in 2016 for alleged criminal conspiracy, fabrication of evidence, illegal detention, and physical violence, but not for murder. When Leonard approached the Bombay High Court to include murder charges, it took three years for the court to order the CBI to add IPC Section 302 in 2019. Even then, nothing moved forward.

“The accused then challenged this in the Supreme Court, which directed the trial court to hear the matter afresh. This was again challenged, this time in the High Court,” said Payoshi Roy, the lawyer representing the Valdaris family.

The eight accused officers moved in separate batches, with different outcomes creating further delays. The trial against seven officers charged under Section 302 has been stalled since 2019, pending the High Court’s decision on whether the main accused, Jitendra Rathod, should face murder charges.

“What makes these cases especially difficult is the deep financial and power imbalance…the victims’ families are extremely poor, while the police officers have the resources to pursue prolonged and expensive litigation,” claimed Roy.

Meanwhile, the accused policemen are reinstated in their jobs. “They’re back to their lives,” Leonard claimed. “And I am still slogging, watching my hope die a little each day.”

The CID had named 14 policemen in its investigation into the 2003 custodial death of Khwaja Yunus, but the Maharashtra government had granted sanction to prosecute only four: Sub Inspector Sachin Vaze and constables Rajendra Tiwari, Sunil Desai, and Rajaram Nikam. All four were suspended in 2004, and Vaze later resigned in 2007. Despite the charges, they were reinstated into the Mumbai Police in June 2020, following the recommendation of a review committee led by then Police Commissioner Param Bir Singh.

Newslaundry reached out to Inspector Jitendra Rathod, who was the in-charge of the Wadala GRP police station at the time of the incident and is now posted in a traffic unit of the Thane commissionerate, for comment. This report will be updated if a response is received.

In Parbhani, Asiya’s 22-year-old vigil

In Parbhani district, 80-year-old Asiya Begum has maintained a 22-year vigil to seek justice for her son’s death – a battle that has outlasted her husband’s life and one that she thinks may go on even when she dies.

“At this pace,” she says with the weariness of two decades spent in courtrooms, “I doubt the case will reach any conclusion even after I am gone.”

Her son, Khwaja Yunus, was a 27-year-old software engineer arrested in December 2002 in connection with the Ghatkopar bomb blast. Less than a month later, the Mumbai police claimed he escaped during a transfer to Aurangabad.

A CID inquiry after a petition by Yunus’s father later revealed that Yunus died due to custodial torture at Ghatkopar police station. His body remains missing to this day.

Five years ago, despite age-related ailments, Asiya never missed a single hearing. “I have religiously read the newspapers every day for the last 18 years, hoping to see the headline that says the men who killed my son have finally been punished…Now I wonder if that day will ever come.”

The CID had named 14 policemen in its investigation into the 2003 custodial death of Khwaja Yunus, but the Maharashtra government had granted sanction to prosecute only four: Sub Inspector Sachin Vaze and constables Rajendra Tiwari, Sunil Desai, and Rajaram Nikam. All four were suspended in 2004, and Vaze later resigned in 2007. Despite the charges, they were reinstated into the Mumbai Police in June 2020, following the recommendation of a review committee led by then Police Commissioner Param Bir Singh.

The case was formally admitted for trial only in 2009, six years after Yunus’s death. Pending the grant of official sanction to prosecute officials, actual proceedings began as late as May 2017. Hearings finally commenced in early 2018 under Special Public Prosecutor Dhiraj Mirajkar. But Mirajkar was later removed after he sought to name more policemen as accused. His removal stalled the trial for nearly four years due to the government’s failure to appoint a replacement.

The Sessions Court repeatedly criticised the slow pace and the government’s handling of the case. It wasn’t until June 2022 that a new prosecutor, Pradip Gharat, was appointed, after which hearings resumed. However, in the two years since, only one witness has deposed. More than two decades after Yunus’s death, the trial drags on.

Sayyad Hussain, brother of Khwaja Yunus, claims, “The policemen who killed my brother lived their lives freely, enjoyed their youth, and faced no consequences, while my family has been left to suffer. My father died waiting for justice. My mother is nearing the end of her life. I don’t know when justice will be done or if I will ever live to see it.”

Newslaundry reached out to Pradeep Gharat, the special public prosecutor appointed by the state government in the case. “Sachin Vaze has been filing one application after another to obstruct the trial. He even moved a discharge application after a witness had already been examined. It’s clearly an attempt to delay the proceedings. I have urged the court to issue a notice to his lawyer, asking on what basis such an application can be filed at this stage, and to justify why it shouldn’t be deemed illegal.”

Vaze is currently in jail. His lawyer could not be reached for comment.

Holes in Maharashtra’s new policy?

On April 15, during a cabinet meeting, Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis announced a new policy to offer fixed compensation for custodial deaths: Rs 5 lakh for “unnatural” deaths and Rs 1 lakh for suicides. According to the Chief Minister’s Office, “unnatural” includes deaths from medical negligence, accidents, jail staff assaults, or inmate violence.

Fadnavis claimed the policy aligns with National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) guidelines, but key aspects of the NHRC’s mandate – such as fixing accountability and prosecuting negligent officials – were absent.

This omission is especially troubling given Maharashtra’s poor record on custodial deaths.

The 1994 study by the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy cited previously in this report had pointed to systemic efforts by police to conceal custodial deaths and instances of torture. Common cover-up methods included failing to register complaints, denying that the person was in custody, falsifying post-mortems, tampering with records, intimidating witnesses, and assigning internal inquiries to officers from the same unit. The study also noted the complicity of doctors and magistrates, who were found to assist in these efforts by fabricating medical reports or suppressing evidence.

Police often attributed deaths in custody to suicide, illness, heart attacks, accidents, or escape attempts even when circumstances pointed to foul play. In several cases, they denied the person had ever been in custody, falsely claiming the death occurred during armed encounters. Victims’ families reported being coerced into signing statements attributing the death to natural causes and, at times, being offered bribes for their silence. In extreme cases, police reportedly disposed of bodies secretly to prevent further investigation or exhumation.

The report concluded that the widespread use of torture stemmed from a deep-rooted culture of impunity, where police operated with the belief that they would not face consequences.

This report was made possible by those who contributed to our NL Sena project on police impunity. Help us tell more stories that are in public interest. Subscribe today.