The swagger’s gone: What the last two decades taught me about India’s fading growth dream

As the youth dividend peaks and inequality deepens, Vivek Kaul asks if we can still revive the optimism of the early 2000s – before the window shuts.

Because something is happening here but you don't know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?

– Bob Dylan, Ballad of a Thin Man, Highway 61 Revisited, 1965.

I was offered my first job in Mumbai on a very rainy day in September 2005, a few weeks after we had celebrated the 59th Independence Day.

It was the season of swagger. India was the “next China,” the stock market was in overdrive, and optimism poured thicker than the monsoon rain.

As a personal finance writer for a daily newspaper, I met those in the business of managing other people’s money (OPM) – or fund managers as they are more popularly known – and not one of them could stop gushing about what they called the India growth story.

For the next few years, almost every OPM wallah I met, told me over and over again that the India growth story would run strong for decades to come.

And they sure weren’t wrong about it – at least in the short term: Between 2005-06 and 2007-08, the Indian economy grew at a pace faster than 9 percent a year (at 2004-05 constant prices) – a feat never seen before in our history. The country felt unstoppable.

Then came the 2008 financial crisis, and the “next China” dream unravelled faster than I could say Jack Robinson. Bad loans worth over Rs 10 lakh crore piled up with banks. Inflation hit double digits. Many corporates ended up building supply capacity for which there was no real demand.

This was followed by demonetisation, a hurried GST rollout, and the Covid pandemic – each pulling the economy further away from that 9 percent orbit.

From 2007-08 to 2024-25, growth averaged a little over 6 percent a year (2011-12 constant prices). As the history of economic growth tells us, even that’s pretty good – but at 6 percent, an economy doubles in about 12 years; at 9 percent, it takes just eight.

Also, whether the growth is equitable and well-spread out throughout a country matters quite a bit.

On August 15, 2025, India marks its 79th Independence Day, and we complete 78 years of independence. Nearly 20 years have passed since that rainy day when I arrived in the city that never sleeps, the city with the fabled “spirit” that keeps it going.

Two decades later, the optimism has thinned, unless you believe everything that gets shared on WhatsApp.

The demographic dividend that powered the swagger is peaking – and without urgent reforms in jobs, education, health, and the ease of doing business, the promise could just slip away.

The spirit’s still there. The question is – is the swagger?

The India growth story

Complicated arguments that can be summarised in a few words tend to sell much better.

So, what was/is the India growth story? At a simple level, it’s basically India’s demographic dividend. But the pitch of India’s demographic dividend is nowhere as saleable as the India growth story.

And what is the demographic dividend?

The demographic dividend is a period, spanning a few decades in a country’s lifecycle, when declining birth rates reduce the share of dependents – children and older people in the population – resulting in a relatively larger proportion of working-age people, particularly the youth (those in the 15-29 age bracket).

As more youth enter the workforce, secure jobs, earn incomes, and spend money, economic growth is expected to accelerate in comparison to earlier periods. This shift can boost economic growth, as a bigger share of the population is able to work, spend, save, and invest.

However, the dividend is not automatic. Its benefits hinge on creating enough jobs, investing in education and skills, improving health outcomes, and implementing supportive economic policies – designed by politicians and bureaucrats – that make it easier to do business.

In other words, favourable demographics can create the potential for faster growth, but they do not guarantee it – without the right policies and institutional capacity, that potential can easily be squandered.

And why is that? The history of economic growth shows us that countries that can cash in on their demographic dividend tend to do so by first manufacturing low-end goods that require low skills to make – simple consumer products like clothes, toys, shoes, snacks, assembly of electronic goods, and bicycles – for the export market.

India has missed out on this economic formula of manufacturing for exports. In fact, as I had pointed out in an earlier piece for Newslaundry, if we look at data from 1980-81 to 2024-25, the share of manufacturing in the Indian economy peaked in 1995-96 at 17.9 percent, close to three decades back. In 2024-25, it was at 12.6 percent, the lowest since 1980-81.

Donald Trump’s import tariffs of 50 percent will make it even more difficult now to manufacture for the US market, India’s largest goods export market.

Skewed manufacturing

A bulk of the manufacturing in India happens in just four states – Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Data from the Reserve Bank of India’s Handbook of Statistics of Indian States shows that in 2022-23, the latest complete data that is available, these states were responsible for a little under half of Indian manufacturing (48.6 percent to be very precise, in current prices).

Uttar Pradesh comes in at the fifth position, after these states. But absolute numbers can be misleading. The manufacturing sector’s share in the Uttar Pradesh economy – or the state’s gross domestic product – was at around 10.4 percent in 2022-23.

If we look at Gujarat, the share was 30.6 percent. For Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, it was at 13.5 percent, 18.1 percent and 11.9 percent, respectively. Of course, these states have a significant presence of the information technology sector as well, which Gujarat largely doesn’t.

In the case of Bihar, one of the most populated states in India, the ratio is 6.8 percent. Interestingly, even in absolute terms, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh are bigger than Bihar when it comes to the manufacturing sector. For Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, the ratio is 7.1 percent and 10.5 percent, respectively.

The overall point is very simple: Most of India’s job creating economic activity is happening in the western and the southern parts of the country, that is peninsular India. And this economic inequality is what needs to be tackled on a war footing if India needs to cash in on its demographic dividend.

The Ranchi story – or how economic activity helps

I grew up in a public sector colony on Kanke Road, Ranchi, in what was then the state of Bihar. My father used to work for one of the Coal India companies. The road I grew up on had three Coal India colonies. We stayed in one of these colonies.

The whole economy of the area depended on someone somewhere digging up coal: from banks to grocery shops to vegetable vendors to the guys selling Chinese food – cooked in mustard oil, with vegetables dripped with ajinomoto (monosodium glutamate), flying in the night-time air.

In the years to come, many Coal India employees moved into new flats that were built in the area, first in order to get the house rent allowance, which they wouldn’t get if they continued staying in the colonies, and then as they started to retire.

This is how economic activity benefits the larger economy in an indirect way.

Indeed, this is what has happened in cities like Bengaluru, Pune, Chennai, Hyderabad and Noida. As information technology companies set up shop, the indirect effects were huge. There was a job boom, and it wasn’t just for engineers and/or MBAs, but also for drivers, cooks, maids, general labourers, electricians, plumbers, masons, security guards and so on. Real estate companies made a killing. So did banks, restaurants, gaming arcades, malls, multiplexes, beauty parlours, app cabs, quick commerce companies, financial advisors, and many other service businesses.

But this growth engine has become concentrated in a few large cities in a few states. And that has led to traffic, long travelling time to and from office, not enough public spaces, extremely expensive real estate, environmental degradation leading to floods in many cities, expensive schools, and so on.

Indeed, it’s this inequality that India needs to set right if its economic growth has to be more equitable and well-distributed in the years to come. The growth engines need to spread from a few states and a few cities, and move towards other states, cities and towns.

Now, talking about Ranchi again. One thing I have never really been able to figure out is why information technology companies haven't set up shop in the city I grew up in.

It has had an airport for more than 60 years. The railway station is reasonably well-connected to the bigger cities. It has a pretty good school education system as well. These are factors that prospective employees and their employers may look at before moving to a new city. (And above all this, there is MS Dhoni as well, who continues to live there, despite his massive success.)

So, what has stopped the tech companies? Is it the bad reputation of erstwhile Bihar, which continues to rub on?

It can also be argued that Ranchi doesn’t have enough engineering colleges like Bengaluru, Pune or Hyderabad. But one can counterargue that engineering colleges started booming in these cities only after the tech companies came.

Or maybe the state’s governments over the years haven’t done enough to attract these companies? I really don’t know the answer and hence, can only speculate about it: but the question continues to bother me.

Now, this might make me sound like a broken record, but economic activity needs to spread across states and not just be concentrated in a few states, as is currently the case.

This means that state and local governments have to take more interest, which doesn’t seem to be the case currently (I am talking about India as a whole here and not just Ranchi and the government of Jharkhand). It might be because such efforts don’t translate into votes easily or immediately, for that matter, or perhaps these governments do not have enough state capacity to tackle a complex problem like this.

Over the years, Indian governments have tried to do too much at once, stretching themselves too thin, without really having the resources or the expertise to deliver effectively.

But as far as solutions go, this is the long and the short of it.

Unemployment and the labour force

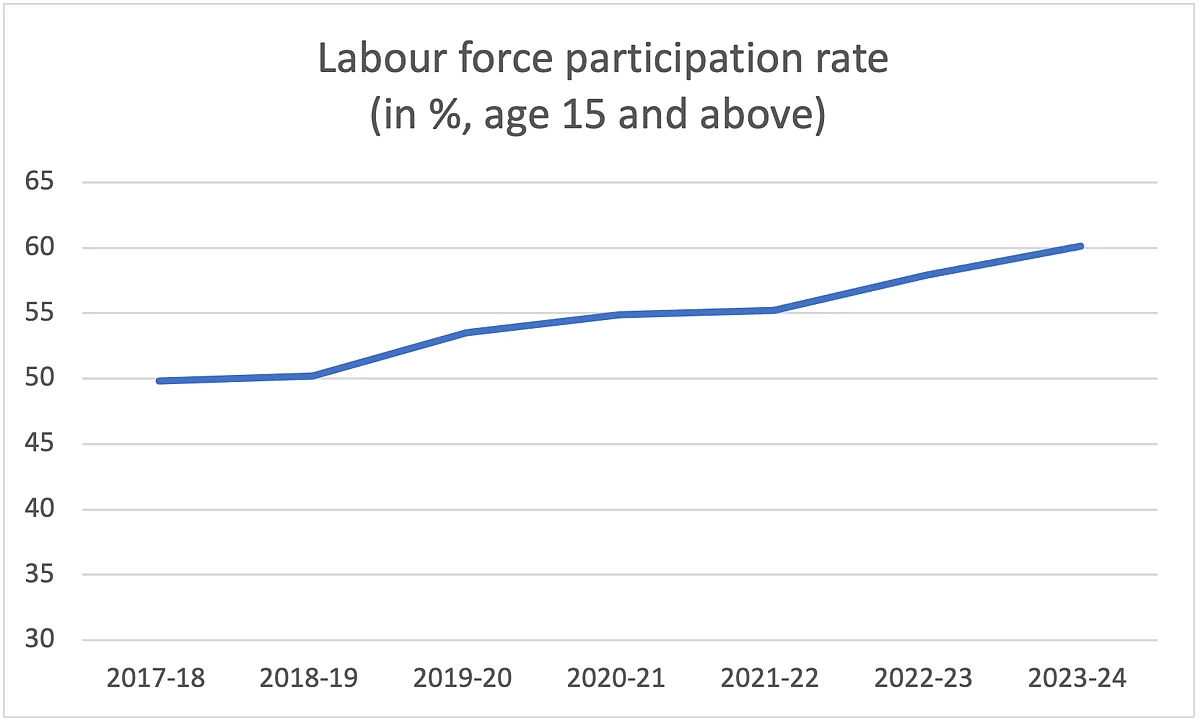

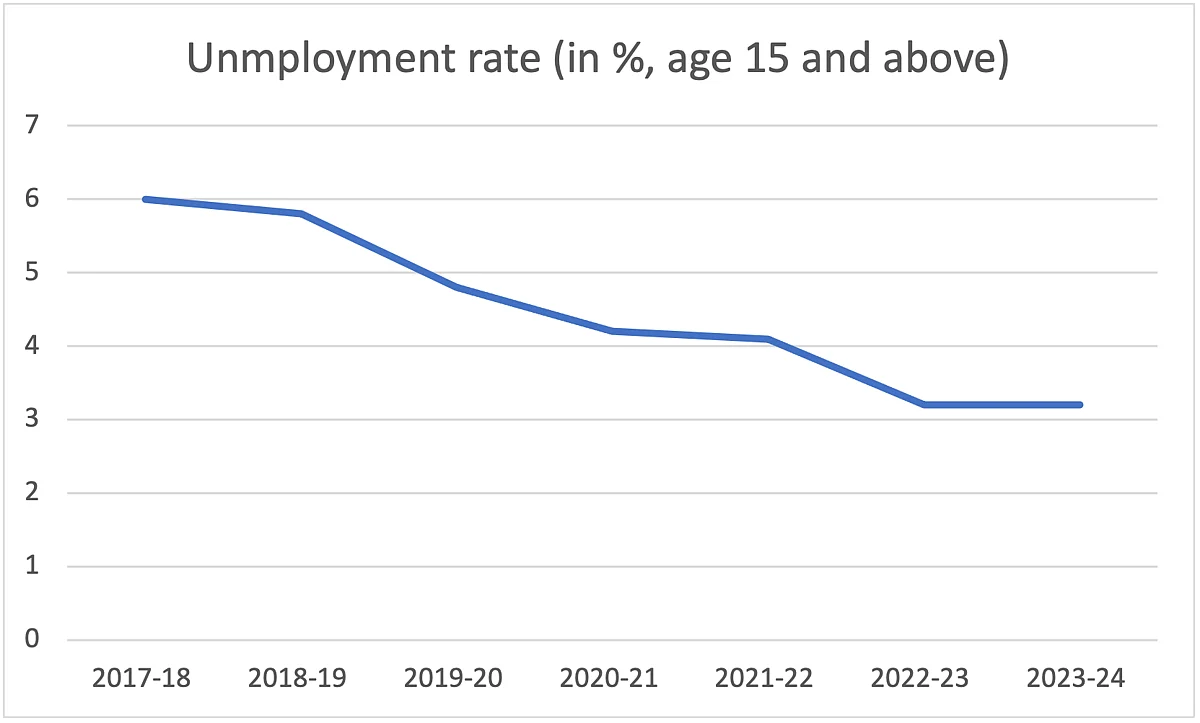

Take a look at the following two charts. The first chart plots the labour force participation rate. The second plots the unemployment rate. These data points are from the government’s Periodic Labour Force Survey, and are sourced from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Economic Outlook database.

The survey is carried out by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation from July of one year to June of the next year.

So, what’s the labour force participation rate? As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey, it’s “the percentage of persons in [the] labour force (i.e, working or seeking or available for work) in the population.” And what’s the unemployment rate? It’s the percentage of persons unemployed among the persons in the labour force.

As per the above two charts, the labour force participation rate has gone up over the years. At the same time, the unemployment rate has fallen, implying that more people are a part of the labour force and are gainfully employed.

So, why am I writing this piece? What’s to worry?

The increase in the labour force participation rate and the decrease in unemployment are primarily on account of more females becoming a part of the labour force and finding employment.

In 2017-18, the female labour force participation rate (15 years and above) was 23.3 percent. By 2023-24, this had jumped to 41.7 percent. The female unemployment rate fell from 5.6 percent to 3.2 percent during the period.

How has this happened? As Chaitra Purushotham of Goldman Sachs Research put it in a recent research note titled The Economic Opportunity of India’s Women Workers: “Official Indian labour statistics show a higher participation rate, possibly because they count unpaid women workers who assist in household and other non-farm activities.”

A similar point is made by Shamim Ara and Puneet Kumar Shrivastav who work for the Indian Economic Service and the National Institute of Labour Economics Research and Development, respectively, in the Economic and Political Weekly, where they write in their personal capacity: “An increase in the female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) in India is largely driven by the female work participation in rural areas and in own-account and unpaid work category of self-employment activities in agriculture and the unorganised sector.”

So, one reason behind unemployment coming down is because of the way it’s calculated. Also, as Azim Premji University’s State of Working India 2023 report points out: “Female employment rates have risen since 2019 due to a distress-led increase in self-employment.” This is another factor that needs to be kept in mind.

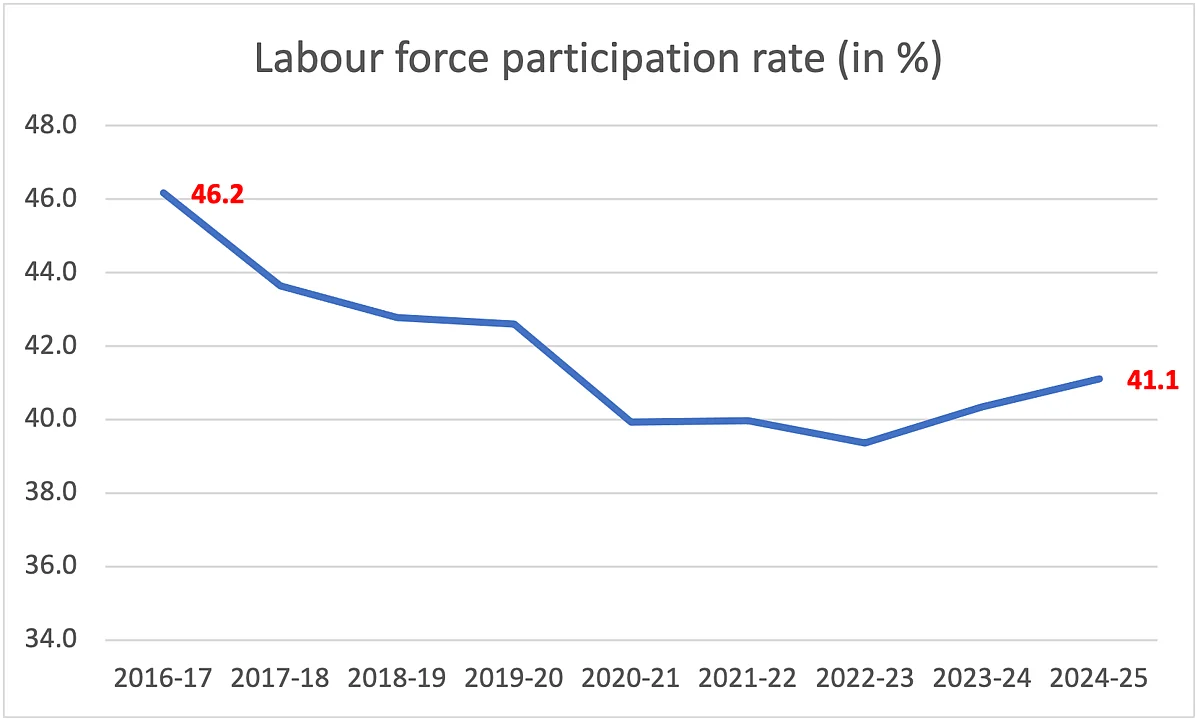

Now, let’s look at the labour force participation rate as measured by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey.

The labour force participation rate has fallen from 46.2 percent in 2016-17 to 41.1 percent in 2024-25. It was at 40.4 percent in 2023-24.

This is more in line with the observed reality of the day because it seems to take into account the negative economic impact of demonetisation, the botched-up implementation of the goods and services tax, the Covid pandemic, and the fact that the private sector hasn’t really been gung-ho about investing in the Indian economy.

To be considered part of the labour force, a person must be at least 15 years old, either employed or unemployed, and both available for work and actively looking for a job.

The phrase actively looking for a job is the important bit here. In short, simply waiting for a job offer does not count as actively looking for work, and a person doing this doesn’t get counted as a part of the labour force.

So the decline in the labour force participation rate can be explained by the fact that many people who couldn’t find employment have probably given up looking altogether and hence, dropped out of the labour force.

Another reason for the fall is possibly the zeal in an average Indian youth to land a government job. They keep trying until they cross the age level beyond which they cannot apply for these jobs. The youth preparing for these exams do not search for other jobs and hence, don’t get counted as a part of the labour force.

Disguised unemployment in agriculture

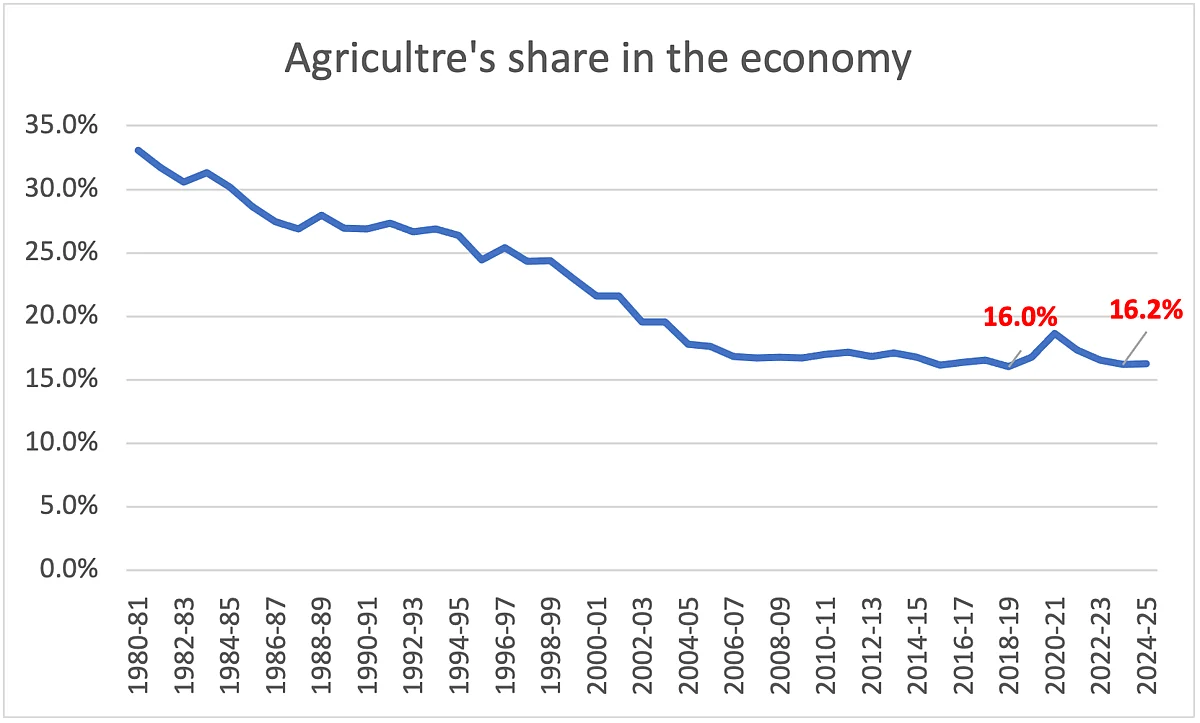

Take a look at the following chart. It plots the share of agriculture in the Indian economy over the years.

Agriculture’s share in the Indian economy has flattened at 16-17 percent for the last 20 years (not considering the bump during the pandemic).

In 2018-19, agriculture formed 16 percent of the Indian economy. It employed 42.5 percent of the labour force. In 2023-24, it formed 16.2 percent of the economy and employed 46.1 percent of the labour force.

This raises several points.

First, more people are working in agriculture, despite its share in the economy barely moving. This is obviously not a good thing. It implies they have either lost their jobs in other, more productive sectors or can’t find one outside agriculture.

Second, agriculture has a lot of disguised unemployment, implying that there are way too many people trying to make a living out of agriculture than is economically viable.

On the face of it, they seem employed. Nevertheless, their employment is not wholly productive, given that agricultural production would not suffer even if some of these employed people stopped working.

Third, the history of economic development shows us that countries have gone from being developing countries to becoming developed countries by moving people from low-productive agriculture to more productive manufacturing and industry. That isn’t happening in India.

If we consider manufacturing, mining and quarrying, and electricity and water sectors, the proportion of the labour force working in these sectors in 2018-19 stood at 13.1 percent. By 2023-24, this had fallen to 12.1 percent. The gap between these sectors and agriculture is huge.

Indeed, this is the gap that needs to be narrowed in the years to come, by trying to initiate economic activity in productive sectors in states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and so on. This is what is needed for India’s youth.

The political will

As Ruchir Sharma writes in The 10 Rules of Successful Nations: “The [demographic] ‘dividend' pays off only if political leaders create the environment necessary to attract investment and generate jobs… India…had assumed that its booming population would provide a demographic dividend, but now it struggles to generate jobs for all its youth.”

To truly capitalise on India’s demographic dividend – for however long this window remains open – elected politicians must move beyond slogans and piecemeal interventions.

They need to build robust and transparent systems that consistently deliver better outcomes in education, healthcare, and the ease of doing business, than is the case currently. This means improving the quality of schools and vocational training so that young people are employable and competitive globally. Rote learning, which has formed the core of the education system, needs to go out of the window.

It means ensuring public health systems keep the workforce productive and resilient.

It also means streamlining regulations, cutting red tape, and actively courting investments – not as a one-off announcement, which Indian state governments seem to be terrific at, but as a sustained, state-level strategy.

Leaders must be willing to compete for capital, showcase credible reforms, and be honest about the challenges their states face. Of course, the centralisation of power with the union government doesn’t help this cause.

And doing all this is hard. Indeed, very hard. It’s just easier to transfer money directly into the bank accounts of citizens, as has become popular amongst elected politicians these days.

Cash transfers

In fact, the Economic Survey 2022-23 highlighted that, as of December 2022, over 2,000 cash transfer schemes were being implemented by various state governments.

As the Survey noted, advances in technology have significantly improved the precise identification and targeting of beneficiaries, helping to reduce leakages and enhance the efficiency of benefit delivery.

The better delivery of cash transfers and other government subsidies has changed the incentives at play for politicians.

This is something that Raghuram G Rajan and Rohit Lamba point out in their book Breaking the Mould—Reimagining India’s Economic Future: “The top leadership in the state or national capital can now identify themselves with the delivery of a specific benefit such as cash transfers, toilets, food grains, gas cylinders or education loans, and directly build a personal rapport with the voter.”

And this helps the bigger politicians, who operate at the central level or at least at the level of a particular state. They can build their brand image by majorly associating themselves with a particular cash transfer or a subsidy that their government offers or plans to offer to the citizens.

As Rajan and Lamba write: “So, the new Indian welfare state is cleaner, but it aggrandizes [enhances power] political leaders more, and for this reason they may have an incentive to skimp even more on the delivery of public services and tilt towards targeted benefits.”

Building systems that create jobs takes time, effort, mental bandwidth, energy and state capacity. Distributing targeted benefits – everything from cash to different kinds of subsidies – is easier. This has become very clear in quite a few recent state assembly elections.

Now, this is not to say that targeted benefits are uniformly bad – not at all. But when they come at the cost of building institutional systems which help create economic activity and jobs, there is clearly a problem. They come with their own opportunity costs.

Of course, as I have pointed out in the past, the investments made by the Indian private/corporate sector in the economy have been sagging for a while. And that doesn’t help either.

Indeed, to fund these targeted benefits and subsidies, the governments need to continue to earn high tax and non-tax revenue.

From 2021-22 to 2024-25, the total receipts of the central and state governments have stood at 29-30 percent of the gross domestic product, something never seen earlier. So, the governments will have to keep figuring out newer ways to keep earning money to fund the welfare state.

The peak demographic dividend

What makes things more difficult is that the number of youth (15-29 years) in India, or India’s demographic dividend in simple terms, may have already peaked. A government report titled Youth in India 2022 points out: “The total youth population increased from 222.7 million in 1991 to 333.4 million in 2011.”

The report estimates that the total number of youth in 2021 was at a peak level of 371.4 million. It further estimates that the number of youth will decline hereon to 367.4 million in 2026, 356.6 million by 2031 and 345.5 million by 2036.

In fact, as the report points out: “In Kerala, the peak was attained in 1991…. In Tamil Nadu …[the] youth population[was] lower in 2011 as compared to 2001 and shows a declining trend since then.” But the defining point is: “States of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh experienced rise in proportion of youth population to total population till 2021, and then is expected to start declining.”

So, the demographic dividend isn’t going to last forever. And the time to cash in on it is now and over the next few years.

India’s youth bulge was never a guarantee of prosperity – only a window of opportunity. That window is now narrowing, with the number of young people set to decline in the coming years.

To truly reap the demographic dividend, India must spread out economic activity and economic growth beyond a handful of states and cities, overhaul education rapidly to produce job-ready talent, and attract manufacturing and industrial investment.

Each one of these is a complex issue. Hence, politics has tilted towards easier, vote-friendly cash transfers and solving issues on WhatsApp through forwards, which tell us that the India growth story is still going very strong.

Without bold, sustained governance, our demographic strength could morph into a liability – perhaps, it already is. The time to act is now. But is that going to happen? Definitely, on WhatsApp, where the India growth story is perpetually booming.

Vivek Kaul is an economic commentator and a writer.

A free democracy needs a free press. Our Independence Day offer lets you gift a free joint subscription to anyone you like.