Footpaths turn to front yards, parking lots in Gulmohar Park, Neeti Bagh

In Delhi’s elite colonies, residents block pedestrian walkways, turning public space into private property.

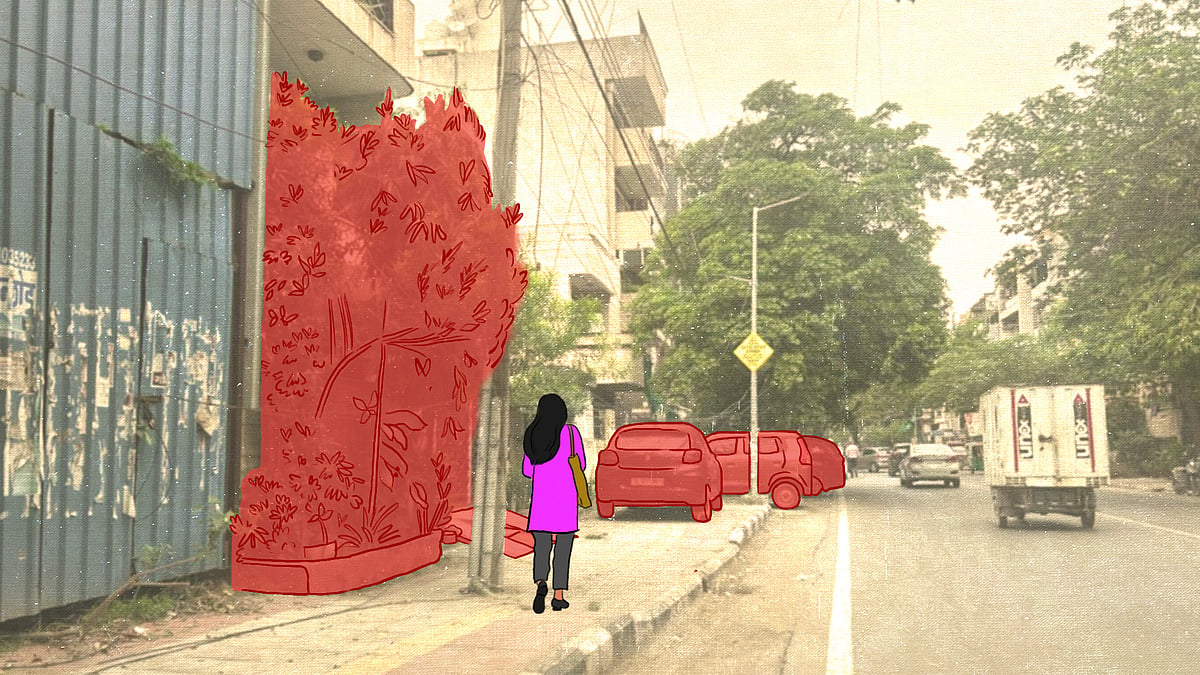

Lush green plants, towering like small trees, overflow the boundary walls of a house. At first glance, it looks more like a garden than a home. However, this is no ordinary yard but a case of private encroachment onto public footpaths in one of Delhi’s most exclusive neighbourhoods: Gulmohar Park.

“This is a problem of privilege,” says Nirupama Verma, RWA president. “The privileged feel entitled to everything, so they take over public space.”

Home to celebrities, politicians and a popular film-shoot location (movies like Pink and Vicky Donor were filmed here), Gulmohar Park began more humbly as Delhi’s first journalists’ colony – named after the vibrant Gulmohar trees that line its streets. In the 1960s, journalists, then modestly paid and ineligible for government housing, formed cooperative societies to secure land from the Delhi Development Authority. By 1969, 325 plots had been allotted for just Rs 35 per square yard, bringing the cost to Rs 41.87 per square metre. The cost today in the colony is at least Rs 7 lakh per square metre.

Today, Gulmohar Park may seem picture-perfect: pristine houses, flower pots perched on white walls, and guards at every gate. Yet a simple walk reveals the reality – footpaths blocked by guard cabins, planters, driveways, and even entire private gardens, making pedestrians feel like trespassers.

The Indian Roads Congress recommends a footpath width of 1.8 metres and a height of no more than 150mm. However, such standards are scarcely met here; often, footpaths are missing altogether.

In B block, houses on Balbir Saxena Marg have footpaths, and occasionally, cars are parked on them. In sharp contrast, encroachments intensified on Wing Commander Mahendra Kumar Jain Marg, where nearly 50 metres of the road was found blocked. Even a Rajya Sabha MP’s home had its footpath claimed by a driveway, security booth, and pots. The length of all encroachments was calculated through Google Maps measurements.

Newslaundry has reached out to the MP for a comment. This report will be updated once they respond.

Passing through Gate Number 7 into the heart of B Block, palatial houses appear, while footpaths almost entirely disappear. Encroachments stretched at least 359 metres across three lanes as the 30 houses here featured planters and vast driveways, resulting in pavements of uneven heights, and making walking hazardous. Similar patterns repeat in A and D blocks: 30 homes in A block encroach 370 metres, while D block adds 330 metres across 32 houses. Many residents, through potted plants and even small trees, have expanded their boundary walls onto public roads.

The problem is so pervasive that when two cars pass, pedestrians are forced onto driveways, if they’re free of parked vehicles.

At the Gulmohar Park Club, a membership for non-residents costs roughly Rs 12 lakh, plus annual fees. Yet, even here, the pavement is encroached for at least 90 metres and choked with parked cars. Encroachment, as Verma admits, is common everywhere, even outside the club.

Footpath encroachment also brings other issues.

“People have built driveways over the storm water drains, ruining the colony’s drainage,” adds General Secretary Anita Dhar Kaul. Despite more than 10 complaints to the MCD in the past year, RWA members say little has been done.

“We have no legal authority; MCD is responsible, but the problem persists,” says Verma.

Encroachment isn’t limited to residential plots; footpaths beside colony parks are similarly blocked by large planters placed by adjacent homes, a local told Newslaundry. In D block, one lane next to a park had 140 metres of footpath seized this way.

Similar encroachments in Neeti Bagh

Right beside Gulmohar Park lies another elite colony: Neeti Bagh. This residential society was founded by practising advocates of the Supreme Court with the vision of creating a well-planned, self-sufficient community for legal professionals. The Delhi Development Authority (DDA) allotted 18.84 acres of land for the construction of residential houses and a dedicated club exclusively for its members. Over the years, Neeti Bagh has developed into a fully established colony featuring a DDA market, landscaped parks, and various recreational facilities.

The colony, established in 1957, has 144 houses. According to current RWA members, it functioned without a formal association for many years after its inception. Although originally intended exclusively for lawyers, only about 30 percent of the current residents are legal professionals, as many have moved out over time, replaced by builders and developers constructing new homes. The minimum cost per square meter in the colony is around Rs 7.5 lakh.

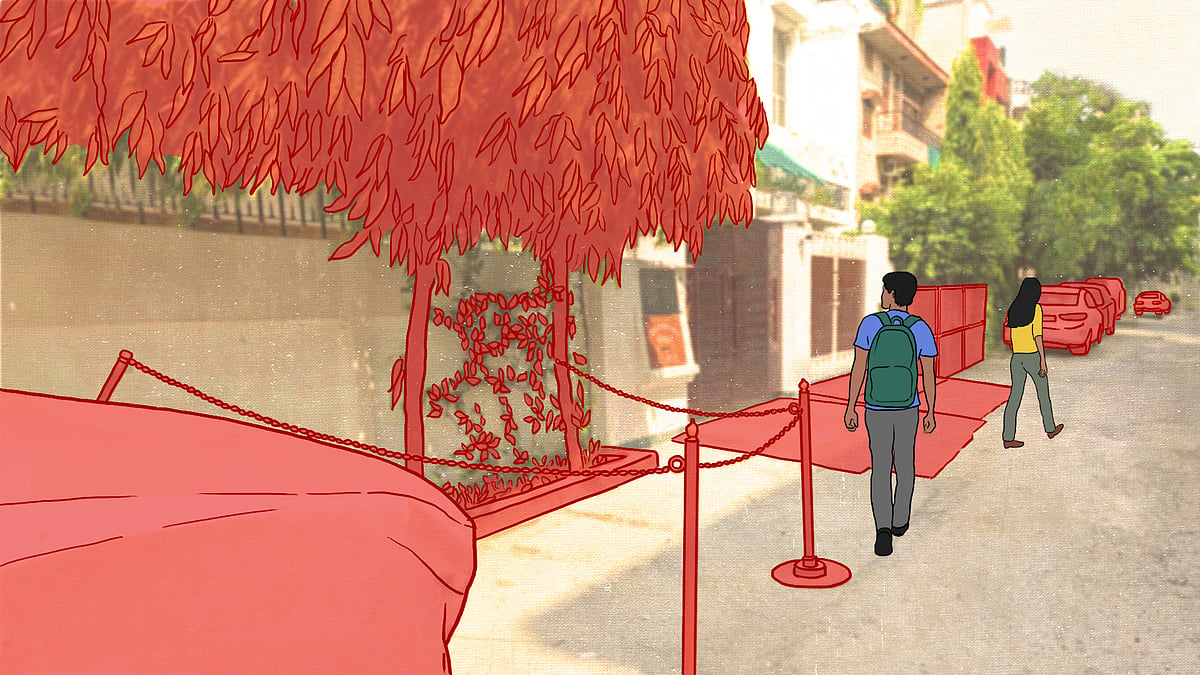

Despite ongoing development, encroachment on footpaths in Neeti Bagh remains widespread. The colony consists of three blocks, all of which Newslaundry visited. The pattern of extended driveways and potted plants obstructing pedestrian pathways seen in Gulmohar Park is prevalent here as well.

In block A, Newslaundry surveyed two lanes comprising 10 houses. The encroachment measured approximately 200 metres in length. In block B, encroachments extended up to 140 metres in one lane with eight houses, and another lane had 140 metres of encroachment, totalling 280 metres of encroachment.

Neeti Bagh’s club is located in block C. The club charges an admission fee of Rs 5 lakh for associate members, according to its website. Behind the club road, across from the park, at least 100 metres of roadway was completely encroached upon by parked cars.

The RWA told Newslaundry that at least three back lanes have been fully encroached by homeowners who have “illegally extended their boundary walls in these lanes, completely encroaching on them”.

In block C, two lanes adjacent to the club each showed significant encroachment: in front of six houses, one lane had 70 metres and the other 109 metres obstructed with driveways and potted plants.

Neeti Bagh RWA general secretary Poonam Gupta acknowledges the persistent encroachment problem, especially around the park, “but MCD hardly does anything. She adds that other issues, including tree pruning and the construction of speed breakers, face similar delays. “We struggle to get these tasks completed,” she says.

Gupta notes that the RWA usually relies on its own funds or intervention by the local MLA to get work done, as the area’s councillor rarely takes action. To curb parking-related encroachments, the RWA is considering imposing an annual fee on residents owning more than three cars, aiming to discourage parking outside personal driveways. “If they are going to park cars anywhere instead of their own driveways, they are encroaching. To discourage that, we are planning to bring yearly fees for the same,” she said.

Experts speak

Dr S Velmurugan, chief scientist and head, traffic engineering and safety division, CSIR-CRRI, said, “The MCD does not make any significant interventions to control encroachments or regulate car parking. People often place planters or pave over the area in front of their homes, extending their private access right up to the gate. This leads to illegal occupation of public space, and as a result, continuous footpaths are missing on many roads due to rampant encroachment.”

He explained that the issue stems from poor planning and weak enforcement, both playing equal roles. “For example, building approvals now considerably increase Floor Area Ratios (FAR), sometimes from 1 to as high as 3.4 or even 4.5, without proper consideration of surrounding infrastructure. This unregulated vertical growth is a major contributing factor.”

Hitesh Vaidya, former director of the National Institute of Urban Affairs, adds, “In Delhi, where one-third of all daily trips are made on foot, encroachments such as chains, security gates, or parked vehicles obstruct public access, particularly in elite neighbourhoods. These are not just legal violations – they infringe on constitutionally protected rights and exclude vulnerable groups from public life.”

He said RWAs or private actors using sidewalks for gates, barricades, or parking violate Indian law and constitutional protections, while also contravening India’s international commitments to inclusive urbanism. He referenced the Draft Master Plan for Delhi 2041 (MPD 2041), which promotes the development of continuous, safe, and universally accessible pedestrian infrastructure. “This alignment of judicial and policy mandates provides a clear directive to prevent any unauthorised privatisation of public pathways.”

Both Gulmohar Park and Neeti Bagh fall under the Hauz Khas constituency. MCD councillor Kamal Bhardwaj said, “We are planning drives in these colonies; they are in the pipeline. The problem is that these ramps or driveways are encroachments that have existed for 10 or 15 years, and no complaints were made then. Now, problems are arising, so we have plans to remove them.”

While the Delhi government plans to improve at least 200 km of footpaths on the city's main roads, it remains to be seen what will happen to the internal roads of these elite colonies.

Newslaundry has reached out to Jitendra Yadav, additional commissioner of MCD South Zone, and Sumit Kumar, Director, Directorate of Press and Information, MCD, for comments. The report will be updated if they respond.

This story is part of our latest Sena project that tracks how elite Indians take over public spaces in urban India. From Delhi to Chennai, Bengaluru to Hyderabad, our reporters will track the worst offenders, the laws being broken, and the price that’s paid by the public – and you.

This is a series that will stand for your rights in your city. Click here to contribute.

Pedestrian zones as driveways, parking lots: The elite encroachments Delhi won’t touch

Pedestrian zones as driveways, parking lots: The elite encroachments Delhi won’t touch In a Delhi neighbourhood, the pedestrian zone wears chains

In a Delhi neighbourhood, the pedestrian zone wears chains