On the ground in Bihar: How a booth-by-booth check revealed what the Election Commission missed

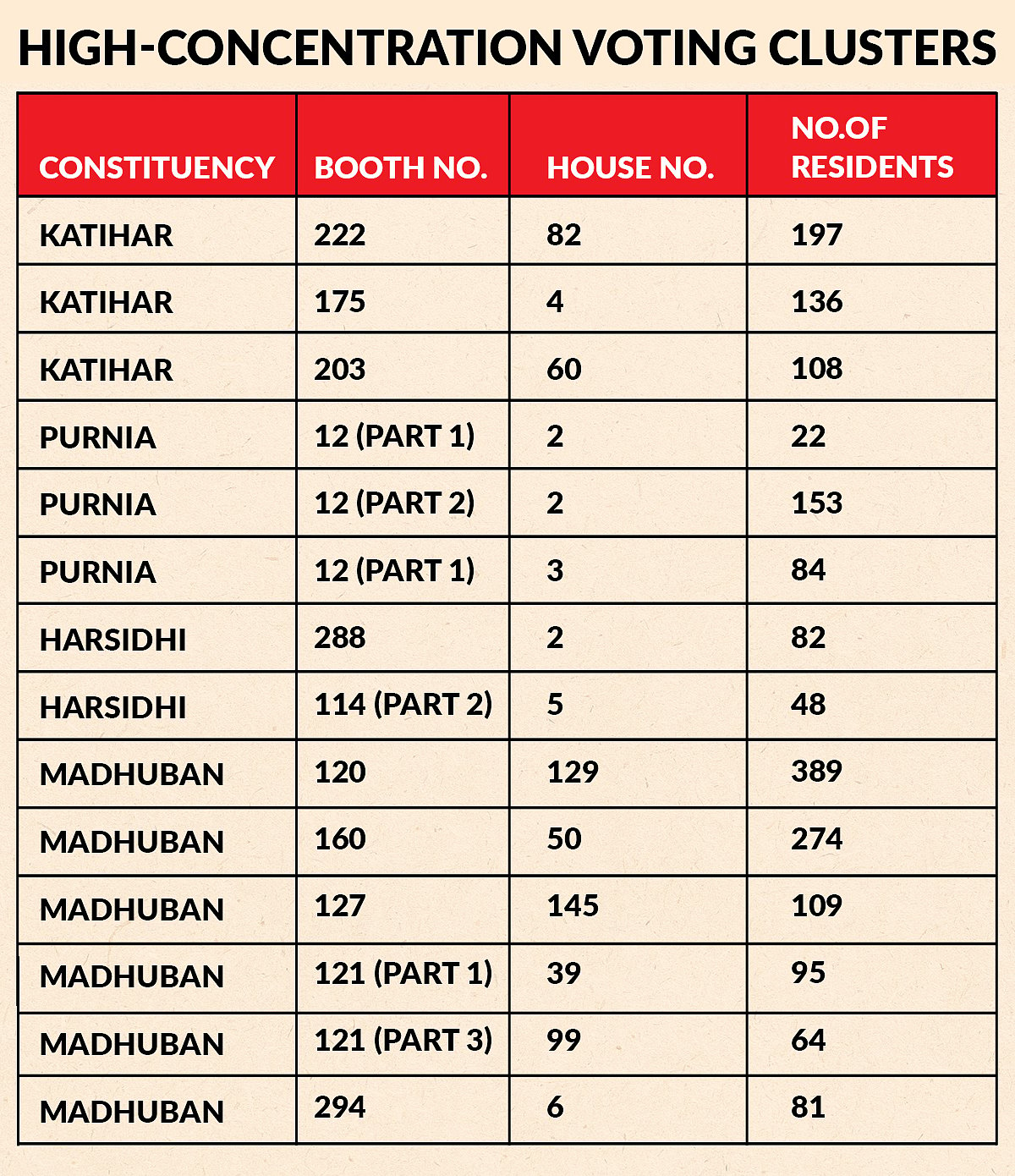

In five constituencies, 1,50,000 voters are clustered around just 1,200-1,300 households, an analysis of the draft electorate rolls revealed. We investigated 14 such cases in four constituencies — some with hundreds registered to a single address.

The credibility of India’s electoral process hinges on the credibility of its voter rolls. The Election Commission of India’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar — an exercise to verify the eligibility of 79 million voters — was meant to ensure this accuracy. It has fallen short.

An ongoing investigation into the draft electoral rolls released by the ECI after it conducted the SIR in Bihar raises troubling questions about its verification methods.

In five constituencies, 1,50,000 voters are clustered around just 1200-1,300 households, an analysis of the voter rolls revealed. We investigated unusually high voter concentrations in 14 such cases — with numbers that ranged from a few dozens to several hundred names registered at a single address.

Interviews with the residents of houses showing unusually high voter registrations and the registered voters themselves revealed that, in many cases, the majority of those listed at a given address were actually living elsewhere. Although many residents identified the voters registered at their address as locals from the same village or area, in four cases, they reported being unfamiliar with some of the names entirely. In one case, two voters were registered to an incorrect address on the rolls even though their voter identity cards reflected the correct address.

The irregularities suggest that the Election Commission, at the very least, failed to carry out thorough door-to-door verification to generate its draft electoral rolls. The accounts of some Booth Level Officers (BLOs) indicate that the ECI’s lack of clarity stalled corrections on ground. These discrepancies leave room for serious doubt over the care with which the commission is conducting the electoral process. At risk is the integrity of the upcoming polls in Bihar.

We sent detailed queries about the irregularities we uncovered to the ECI’s spokesperson. This copy will be updated if they respond.

Voting clusters contradict social realities

Our on-ground investigative team conducted a meticulous, booth-by-booth validation process to examine 14 cases across four constituencies in Bihar: Katihar, Purnia, Madhuban, and Harsidhi. Journalists visited specific addresses with an unusually high number of voters — often ranging in the hundreds — to verify the actual residents of those houses.

The addresses on the voter rolls were frequently vague. Some simply listed entire localities. In others, only the ward number was used as an address for hundreds of voters. Such inconsistencies made the independent verification of voters and addresses next to impossible.

In multiple cases, homes with an occupancy of a handful of people were registered to hundreds of voters. The residents themselves were unaware of the excess voters linked to their address.

Such clusters seemed even more improbable given the social hierarchies inherent to the localities we visited — most of them enforced segregation along religious and caste lines. In Katihar district, for instance, the draft electoral rolls reflected more than a 100 voters registered from one house. These included Muslims and Hindus from privileged and marginalised caste communities. The homeowner of this residence told us that it was unlikely that most people in the list even lived in the same ward.

Mistaken addresses and mysterious identities

According to the draft electoral rolls, two addresses in north-eastern Bihar’s Purnia district — both designated as house number 2 in booth number 12 — are home to 22 and 153 voters, each.

The one with 153 voters is a temple built on a private plot. Chandan Yadav, whose family owns the land on which the temple stands, was not aware of any voters registered to this address.

Krishna Mohan Rai, a retired revenue officer, is among those 153 voters. But his actual residence is house number 269.

The second house, with 22 voters, is owned by Sanjay Kumar Chaurasia, a 60-year-old businessman whose family has lived in that home for over seven decades. He stays there along with nine relatives.

Chaurasia isn’t included in the rolls for the house in which he lives. The Elector Photo Identity Card (EPIC) number assigned to him had mistakenly been allotted to his brother, Chaurasia told us. At the time of our meeting, he was pursuing a resolution to this error.

When we read out a sample from the list of names registered at his address, Chaurasia did not recognise a single one. “This is false, it has been forcefully imposed,” he said.

Pankaj Srivastava — a former candidate for the council of Ward Number 2, where both the addresses designated as house number 2 are located — identified several people on the voter rolls corresponding to these properties as living elsewhere.

Chandan Kumar, the BLO of booth number 12, told us that he hadn’t registered a large number of people to any single address. But he hadn’t strictly adhered to a house numbering system, either. “I don’t know much about house numbers. We don’t go by house numbers. We go by names” he said.

Two other BLOs told us, on the condition of anonymity, that they don’t use house numbers to record voter data either. Kumar became BLO a year ago. He didn’t have much prior experience, he said.

When we showed him the draft electorate rolls, which club dozens of people under the same house, he claimed that the errors didn’t originate at his end. “I have registered people properly,” Kumar told us.

Over 200 kilometres away, in Rajpur Kaul Madpa Maal village — which comes under booth 160 of the Madhuban constituency — 274 voters were registered to one address: house number 50.

This pucca house belongs to the late Gajendra Mandal. His son Rajesh Mandal, who is in his mid-forties, told us that he had lived there his entire life. He had “no idea how so many others were registered in his house,” when only he, his wife, and children stay there.

Patit Pawan Kumar, the local Booth Level Officer (BLO), told us that the problem had existed since before his nearly seven-year-long tenure. Patit said that the booth in which Mandal’s house is located had then been split into two recently, after the number of voters in the booth crossed 1,200 people. However, he added that even the undivided booth had “multiple houses with 100-150 odd residents.”

The 274 people registered to Mandal’s house were legitimate voters who were assigned the wrong house, Patit claimed. The residence proof submitted by voters was often a certificate issued by the local panchayat with no mention of a specific house number, he said.

Patit is awaiting official directions before he initiates any corrections. His supervisor, Dheeraj Kumar — who oversees 13 BLOs in Madhuban —claimed that multiple BLOs have submitted reports to district-level ECI officials on such irregularities, dating as far back as 2010-11. But the ECI “has not acted on them yet,” Dheeraj told us.

Houses on paper, missing on ground

Confusion prevailed about the very existence of an address in some cases.

In Katihar district — the administrative headquarters of Purnia Division in north-eastern Bihar — house number 82 in booth number 222 is officially home to 197 voters, according to the draft electoral rolls. This address, located in the urban constituency of Katihar, was earlier listed under booth number 195 with 252 voters, in the electoral roll that the ECI updated in January 2025.

Our team set off in search of this house, winding through the ward’s narrow lanes to reach a dilapidated structure. It was padlocked.

Perched on a slope, the house frequently flooded during the rains, Shambhu Nath Jha, who stays nearby, told us. It had been shut for over 20 years, following a protracted legal case over its ownership, Jha added. According to him, a man named Dr. A.K. Mishra lived there, and had moved to Begusarai, around 180 kilometres away. (We were unable to verify Mishra’s ownership of the home or the existence of the legal case independently.)

The draft voter rolls list 197 registered voters at house number 82, including a man named Pramod Kumar Agarwal. We found him at house number 183.

“I have no idea about this,” Agarwal said about the discrepancy. He could not identify most of the voters from a sample of the rolls corresponding to house number 82.

Sita Kumari — the BLO of booth number 222 — confirmed that nearly 200 people are registered in this house. “You are right,” she told us. “That is how it was registered in the past. We have to correct it. It will happen now.”

House number 4 in Katihar district’s booth number 175 has 136 registered voters. The address was elusive, a ghost in the official records. We narrowed our search down to two possibilities.

The first: a derelict, shuttered structure that matched the chronological numbering sequence. Beside it, a single gate opened to a cluster of three homes. The numbers “S 2, 3, and 4” were crudely marked on a wall near the entrance. We requested a neighbour for his address to confirm the location. He called the BLO to learn that his own house number was 1.

When we asked the BLO to guide us to house number 4, he referred to his records and directed us to a nearby building. But the house he claimed was the one we were looking for bore an altogether different number. The BLO did not respond to subsequent calls.

We opted for a different approach and followed the sequential pattern to a lane with houses numbered 5, 6, and 7. But the spot at which house number 4 would have stood was occupied by a gym instead. (The gym was shut when we tried to visit it during two separate attempts.)

These were not isolated instances in one district alone.

Turkauliya — a village about 10 kilometres away from Motihari, in northern Bihar’s east Champaran district — is part of the Harsidhi constituency. Homes in this village were undesignated. No one we spoke to was aware of their house numbers.

According to the voter list from booth number 288 here, 82 different voters were registered under a single address: house number 2.

Sant Kumar Ram, a current ward councillor, and Krishna Paswan are both supposed residents of this house. When we met them, they were bewildered to learn that they officially shared a residence with 80 other people. A third voter, listed as a resident — who spoke to us on the condition of anonymity — also confirmed that he did not live in that house.

Ram and Paswan recognised most names on the list. They confirmed that these individuals lived across different neighbourhoods, some in different wards.

Niti Prakash, the BLO for booth number 288, distanced himself from the irregularities. He was newly appointed, and the issue predated his tenure, Prakash said. He was unable to clarify the exact location of the house in question.

Meanwhile, at Harsidhi’s booth number 114 in the Bin Tola neighbourhood at Chadrahiya village, identifying houses was not a problem. Most residents knew their house numbers; they were listed on their EPICs as well. A bulk of the houses in the village were built under the Indira Awas Yojana — since renamed Pradhan Mantri Gramin Awas Yojana — which is why they had been allotted numbers, Ajay Kumar Bin, a ward councillor, told us.

Yet, 48 people were registered to house number 5 here. Only two among them, Lalbabu Bin and his wife, actually resided at the address. Most of the 48 registered voters were from the Bin Tola neighbourhood, while others were from a nearby area, three people from the neighbourhood told us. One of the registered voters lived, for instance, in house number 6.

“This error is from the system and the district administration,” Asgar Ali, the BLO of this booth said. Once the SIR process was underway, BLOs were verbally directed by their supervisors and district-level officers to leave voter rolls unchanged apart from deleting the names of people who had died, moved away, or could not be located, Ali told us. So, even if officials were aware of incorrect house numbers for verified voters, they did not rectify them, he added.

Feature, not a bug

In East Champaran district’s Madhuban constituency, the densest clusters of voter registrations we found were caused by an administrative shortcut.

At booth number 120 in the village of Bishunpur Mohan Urf Marpa, a staggering 389 people were registered under a single address: house number 129. No resident in the area could identify the home.

In a peculiar twist, the BLO for this area is also officially listed as a resident of the same house. The BLO declined to be interviewed when we asked him for a response on this matter.

A local official who requested anonymity because they were not authorised to speak to the media, said that this irregularity has been 15 years in the making. “After the village’s house count reached 129, a procedural flaw took root. Every single new voter since then has been added under the same house,” they told us. All 389 individuals in house number 129 were validated voters, they claimed.

But the process of registering these voters was questionable. As in Rajpur Kaul Madpa Maal village, the documentation submitted by at least one of these voters was a certificate from the local panchayat. It stated that the person resided in the village and ward, but had no mention of their house address. The official confirmed that this was the kind of documentation that most, if not all the 389 people registered to house number 129 had submitted.

Two brothers, Jagannath Paswan and Devnath Paswan, and Nandu Paswan — not a sibling — are all registered voters from house number 129. They are agricultural workers who live in mud-and-thatch houses with their respective families.

None of them knew the designated numbers for their homes. They realised that their official address in the draft electoral rolls was house number 129 only after we spoke to them. Neither were they earlier aware that 386 other individuals, most of them complete strangers, were registered to the same address as them.

Update on Aug 26: In a post on X, Bihar’s Chief Electoral Officer responded to the report a day after it was published. The officer said that voter clustering is a “local socio-geographical reality” in Bihar’s rural and semi-urban areas due to lack of land or house number in the revenue records.

Team Bihar SIR is a collective of freelance reporters.

Data analysis by Ravi Nair, Sachi Hegde, Ayush Joshi, and Raunaq Saraswat.

Ground reporting by Abir Dasgupta, Arun Kumar Dwivedi (Network 10), Mansoor Ahmad (CNews Bharat), and Prabhat Kumar in Madhuban and Harsidhi. Parth M N, Puja Mishra (awaaz 24), Om Prakash Mishra (Bharat 24), Rajiv Raj (Bihar News), Ranjeet Gupta, Santosh Nayak (The Political Leader), Atiq Ahmed, Imran Khan, Jaydev Yadav, and Amit Singh (India Daily Live) in Katihar and Purnia.

Our latest Sena project tracks how elites take over public spaces in urban India, and the price that’s paid by you. Click here to contribute.

CEC Gyanesh Kumar’s defence on Bihar’s ‘0’ house numbers not convincing

CEC Gyanesh Kumar’s defence on Bihar’s ‘0’ house numbers not convincing Exclusive: In 3 Lok Sabha seats swung by BJP, many wrong voter deletions, violations of EC norms

Exclusive: In 3 Lok Sabha seats swung by BJP, many wrong voter deletions, violations of EC norms