Missed red flags, approvals: In Maharashtra’s Rs 1,800 crore land scam, a tale of power and impunity

Neither of the two FIRs named Parth Pawar.

In the 19th century, in the quiet village of Mundhwa on the outskirts of colonial Pune, the British granted 44 acres of land to 26 families from the Mahar community. These land grants, known as Watan land, were in return for their hereditary service as village watchmen, messengers, field measurers, torch-bearers, and sanitation workers.

After Independence, the Mahar Watan Abolition Act of 1950 converted such lands across Maharashtra into regular holdings. Sale or transfer required prior government approval.

But this month, 43.3 acres of that very land in Mundhwa have reignited questions about how property meant for Maharashtra’s most marginalised communities continues to slip into powerful hands.

Seized by the Bombay government in 1955 and leased to the Botanical Survey of India until 2038, the land – now valued at around Rs 1,800 crore – was allegedly sold in May this year to Amadea Enterprises LLP, a company in which Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar’s son, Parth Pawar, is a director. The deal, executed for just Rs 300 crore through a power of attorney held by Pune businesswoman Sheetal Tejwani, allegedly bypassed mandatory state approvals, violated laws governing restricted Watan lands, and even secured a Rs 21-crore stamp duty waiver.

The transaction has triggered two FIRs against Tejwani and several officials. But they notably exclude Parth Pawar, despite his majority stake in the purchasing company.

Facing mounting opposition allegations, Ajit Pawar has defended his son, placing blame on the sub-registrar who cleared the deal. “How did the individual in the sub-registrar’s office register the deed? What prompted him to do the wrong job? We will come to know through the probe,” Pawar said in his hometown, Baramati, adding that Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis had already ordered an investigation.

The State Revenue Department has since suspended sub-registrar Ravindra Taru for alleged irregularities in the registration process. A tehsildar was suspended before.

But to grasp the full significance of this controversy, one must go back to the origins of Watan land – a relic of Maharashtra’s feudal past.

The origin story

Watan land is a term rooted in Maharashtra's socio-historical land tenure system. It refers to land that was traditionally granted to members of several communities, including the Mahars, as compensation – instead of cash payment – for performing hereditary village duties under the old Watan system.

The families that were given this land in Mundhwa by the British had farmed this soil for years. But in September 1955, the then Bombay state government took away the land, citing alleged unpaid taxes of around Rs 1,000 and stating the land had been left uncultivated. Three months later in December, the same land was leased to the Botanical Survey of India to build a botanical garden. What was once a source of their livelihood became government property. And their struggle to reclaim it through title disputes and legal battles began.

53-year-old Prakash Dhale, a resident of Mundhwa and descendant of the Mahar Watandar families, has been trying to reclaim the land since the early nineties. “The Mahar Watan land was originally given to my great-great-grandfather. But in September 1955, the then Bombay government took it away from my grandfather, Tatya Choku Gaikwad, and other families, claiming they hadn’t paid arrears of just Rs 500-1,000 on the entire 43.26 acres. They also said our families hadn’t cultivated the land and left it fallow. Soon after in December 1955, the land was leased to the Botanical Survey of India, though the ownership still remained in our ancestors’ names,” he claimed.

In 1973, the lease to BSI was renewed for 15 years to help the survey expand its Pune centre and set up a botanical garden. Then in early 1990, families of the original Watandars claimed rights to have the land regranted to them. However, they were not given the land and in 2000, the lease was renewed again for 50 years for BSI, effective from 1988 to March 2038.

Dhale alleged the dispossession was systematic. “In 1967, representatives from 19 families applied for regrant, but the government rejected it and offered compensation of just 45 per month instead to each family. Despite repeated petitions from all 26 families, nothing changed.”

Dhale claimed he dug up old records and filed applications with the revenue department. In 1994, a step taken by then revenue minister Vilasrao Deshmukh to hand over Watan land from the state reserve police force to members of the Mahar community in Wanwadi gave him hope. The order by Vilasrao Deshmukh stated that the SDM’s decision to take over the land was illegal.

Despite the similarity between the Wanwadi and Mundhwa cases, the 26 families of Mundhwa never got regrant of the land.

Then, in 2006, the families came into contact with Sheetal Tejwani, a Pune-based builder and businesswoman who claimed that she could help them reclaim their ancestral land. But instead of pursuing their case for regrant, they said that she held on to their power of attorney for nearly two decades. And 19 years later, Tejwani resurfaced at the centre of a major land scam, accused of using those very documents to sell the same 43 acres of Watan land to Amadea Enterprises LLP, a company owned by Parth Pawar.

Seventy-year-old Kalidas Gaikwad, a resident of Mundhwa and one of the descendants of the original Watandar families, recalled how it began. “In 2006, a broker named Umesh More came to us on behalf of Sheetal Tejwani from Paramount Infrastructures and introduced us to her. When we met her, she said she would help us get our land regranted. She took signatures from around 272 members of the 26 families who have their names in the property card and even gave Rs 5,000 to Rs 10,000 to one representative from each family.”

“She took a power of attorney from us, but it was only meant to let her represent us in legal and administrative matters, not to sell the land. She told us she would help us reclaim our land, and maybe even sell it at a good price if we ever wanted to. But she did nothing. Over the years, we kept meeting revenue ministers…but nothing concrete ever happened.”

Raju Dhale, 71, another descendant of the Watandar families, claimed, “In 1955, the government took our land without any notice or explanation. They put their name as the owner, but our ancestors’ names still remained in the 7/12 land records (Bombay state government records)...on the new property card, around 272 of us are still listed. Yet, the land was never returned to us.”

Dhale claimed Sheetal Tejwani “kept fooling us with false promises”. “And now we find out she sold our land to Parth Pawar…without telling us. Such a deal couldn’t have happened without help from ministers, bureaucrats, and officials. Everyone knew this was Mahar Watan land, still leased to the Botanical Survey of India."

Some had even tried to revoke the power of attorney years ago. Prakash Dhale, for instance, sent a legal notice in 2008. “We have been fighting for this land for so long that not a single minister can pretend that he doesn’t know about whether it’s Mahar Watan or not.”

The shock was greater for Nilesh Gaikwad, 28, whose family didn’t even give the power of attorney to Tejwani. “Yet she somehow managed to sell the land that’s in our name. I found out only on November 1, when someone sent me a copy of the Index-2 sale deed. I was shocked as our families have been fighting for years to get this land regranted. The very next day, members from 26 families met and submitted an objection letter to the Haveli Tehsildar, opposing any registration…Later we came to know that the company belonged to Parth Pawar.”

Lalit Babar, head of the Watan Zameen Sangharsh Samiti, an outfit working to reclaim Watan land, and an expert on issues related to Mahar Watan lands across Maharashtra, said, “Mahar Watan lands have dual ownership, one by the erstwhile Bombay government (Mumbai Sarkar) and the other by the community. In 1958, when the Bombay Inferior Village Watan Abolition Act came into force, the government took over the Watan lands given to the Mahar community. But it also allowed individuals to reclaim them by paying three times the annual revenue as nazrana.”

“Some managed to do so, but most couldn’t…Many had no idea about the regrant process because the government never issued formal notices when it acquired their land. Later, when they learned about it and tried to reclaim their land, the government simply refused…We have been urging the state for years to restart the regrant process and return the land to its rightful heirs.”

Maharashtra once had around 5.28 lakh acres of Mahar Watan land but only about 15 to 20 percent has been regranted so far, he said. The rest remains uncultivated, open, or illegally occupied. “That’s why scams like this keep happening.”

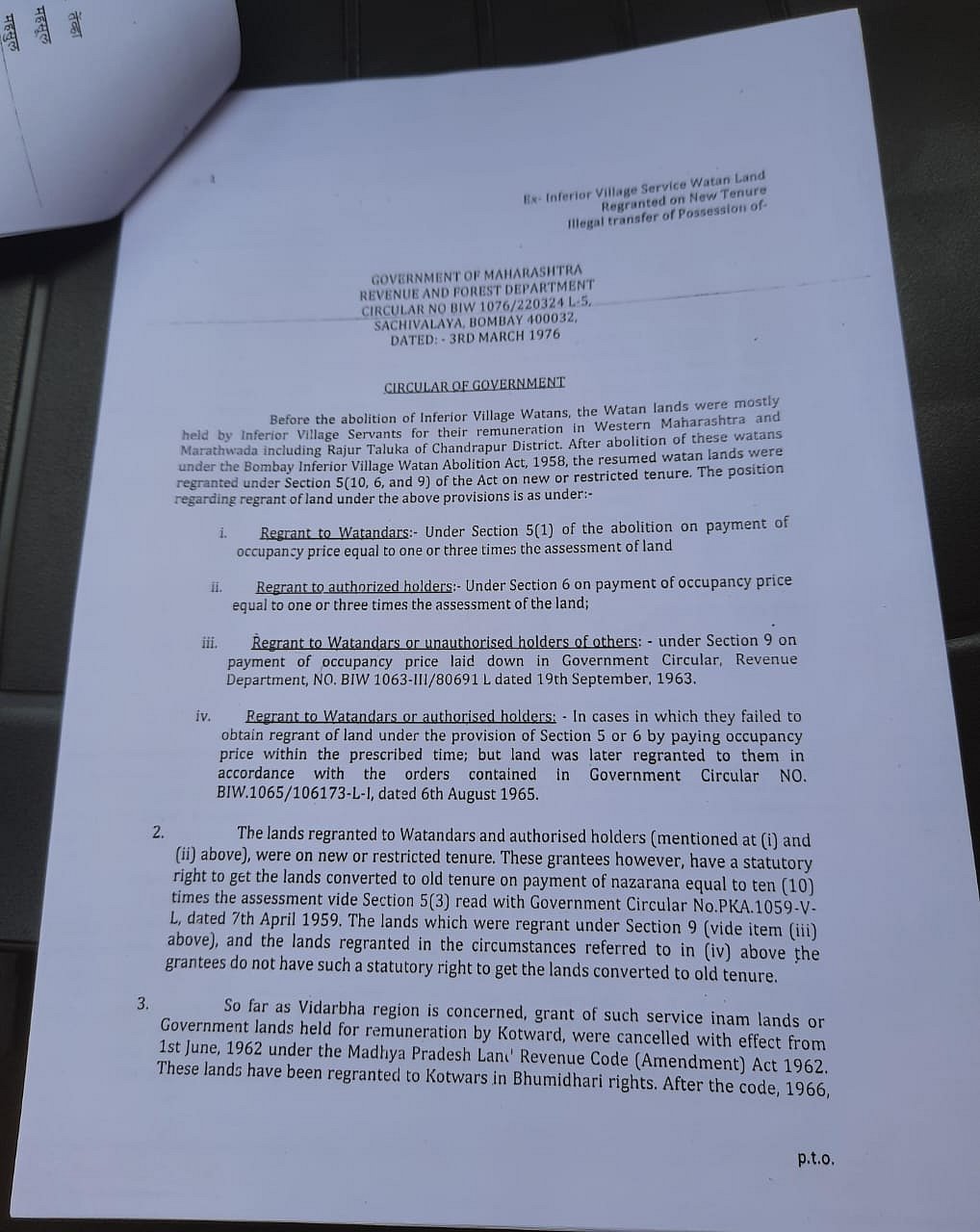

ND Kamble, a scholar with in-depth understanding of Mahar Watan land issues in Maharashtra, said, “It is significant to note that in 1976, the then Chief Minister of Maharashtra, Shankarrao Chavan, issued a government circular concerning Mahar Watan lands. This followed a meeting between Namdeo Dhasal, who led a delegation of the Dalit Panthers Parishad, and Chief Minister Chavan. Dhasal had drawn the government’s attention to the fact that although the Watan Abolition Act had come into effect, the original beneficiaries, the Mahar Watandars, had not been given possession of their land despite repeated appeals. Responding to these concerns, the Chavan government issued a circular directing all district collectors to remove unauthorised occupants and restore the land to the original Mahar Watandars. The circular also clarified that even if the land was in possession of institutions for public purposes such as the Botanical Survey of India or any such institution, the Mahar Watandars retained the right to have it regranted to them.”

Dinesh Kotkar, who also works in real estate, was the first to discover the questionable sale deed. Kotkar, who runs an organisation named Chhava Kamgar Union, said he received a copy of the original Index-II on WhatsApp. “I immediately went to the Joint District Registrar (JDR) and Stamp Duty Collector Santosh Hingane and asked how such a sale could take place, especially when stamp duty worth Rs 21 crore had been waived. Hingane brushed it off, saying everything was in order.”

Tejwani’s past

Sheetal Tejwani and her lawyer husband Sagar Suryavanshi are not new to controversy. They have been booked and arrested in the past for multiple cases of cheating, fraud, forgery, money laundering etc. They were key accused in the Seva Vikas co-operative bank fraud case, a multi-crore scam that caused the bank to collapse, with losses of about Rs 429.6 crore across 124 fake loan accounts.

Through their companies called Paramount Dreambuild Pvt Ltd and Renuka Lawns, they allegedly helped divert Rs 60.67 crore through 10 bogus loan accounts. Suryavanshi was arrested by ED in the case in 2023 but was released on bail by Bombay High Court a year later.

The couple has reportedly been on the run ever since Tejwani’s name surfaced in the Mundhwa land scam and an FIR was filed against her at the Bavdhan police station.

Calls to Suryavanshi’s phone went unanswered. A questionnaire has been sent to him. This report will be updated if a response is received.

How the deal unfolded

By 2025, Mundhwa had transformed into Koregaon Park Annex, one of Pune’s most expensive real estate zones. The same 44 acres that once fed the Mahar families were now worth nearly Rs 1,800 crore.

When the deal came to light, it raised serious questions: How did land leased to a government department until 2038 end up in private hands? How did officials allow the sale? And how did a property meant for the poorest of the poor become a playground for the powerful?

On May 20, 2025, a sale deed was registered between 272 members of the Mahar Gaikwad families and Amadea Enterprises LLP. In the Index-2 of the document, Sheetal Tejwani is listed as the representative of the 272 members of Gaikwad clan, while the company was represented by Digvijay Singh Patil, Parth Pawar’s cousin and a 1 percent partner in the firm.

While the land scam came to light in November 2025, the motion to set it in place began almost 11 months back in December 2024, when Tejwani submitted a letter with signed power of attorney to Pune’s collector. It claimed that a demand draft worth Rs 11,000 had been submitted for the regrant of the land and the land should be handed over to the original Watandars. This was for the land bearing survey number 88, leased to the BSI.

Pune District Collector Jitendra Dudi told Newslaundry, “In December, we received a letter from Sheetal Tejwani on behalf of 272 claimants, stating that the land belonged to the original Watandars and it should be regranted to them. It was claimed they have also submitted the regrant amount to the government through a demand draft and possession of the land should be handed over to them. However, that letter had no legal validity. It was completely illegal and had no procedural basis for taking possession of the land.”

“This land cannot be regranted like that. Even if the government decides to regrant such land, it must first issue an approval, determine the regrant amount as per rules, and then generate a challan. Only after the challan is paid the land can be handed over to the claimants. In this case, Tejwani, who was representing the claimants using power of attorney, didn’t submit any draft; she merely wrote that she had. If anyone could just walk into the collector’s office, claim to have paid money, and demand land possession, it would create complete chaos.”

But on May 20, the sale deed was executed and on May 26, Amadea Enterprises wrote to the Tehsildar informing them that they had occupied the land legally and BSI should evacuate the land. The letter stated, “We inform you that on December 30, 2024, the original farmers have duly deposited the occupancy price. Consequently, it is both appropriate and necessary for your office to issue a formal intimation to the Botanical Survey of India, Pune directing them to vacate the land forthwith since their lease deed stands terminated with immediate effect.”

According to Dudi, Tejwani also submitted a letter to the tehsildar, claiming the regrant money had been deposited and requesting possession of the land. Acting on that, the tehsildar issued an eviction notice to the BSI in June. “When BSI approached us after receiving the eviction order on June 9, we immediately ordered that the tehsildar’s illegal order not be executed. I directed the SDM to look into the matter and stopped the execution of the eviction order. We initiated an inquiry against the tehsildar and recommended action to the state government. He was suspended, in fact, his suspension order was issued a month before this matter became public.”

How did land leased to a government department until 2038 end up in private hands? How did officials allow the sale? And how did a property meant for the poorest of the poor become a playground for the powerful?

Dudi further said that his office stopped the eviction but they were unaware that a sale deed had already been registered. “BSI came to us in June, 2025, and we acted immediately. But at that time, we didn’t know the sale deed had already taken place in May. We found out later. The registration was done by the sub-registrar’s office, which should have informed us, but didn’t.”

Further explaining the process of land transfer, Dudi said, “There are three stages of land transfer, sale deed, mutation (which updates the official land record), and physical possession. In this case, only the sale deed happened; the other two stages never followed.”

He added that the sub-registrar’s office committed three major mistakes, “First, they executed the sale deed using a 7/12 extract, even though Pune now uses property cards for sale transactions. Second, the 7/12 clearly mentioned Mumbai Sarkar meaning it was government land, which cannot be sold without state approval. Yet, they still registered the sale. And third, they waived stamp duty worth Rs 21 crore, which is a serious violation.”

Tehsildar Suryakant Yewale and sub registrar Ravindra Taru both were booked in two separate FIRs registered at Khadak and Bawdhan police stations of Pune.

Tehsildar Suryakant Yewale has a history of disciplinary action and corruption charges. In 2011, while posted as Naib Tehsildar in Umred tehsil of Nagpur, Yewale was caught red-handed by the Anti-Corruption Bureau while accepting a bribe of Rs 10,000. A criminal case was registered against him at the Umred police station in August 2011. Five years later, Yewale was suspended for dereliction of duty during his posting as Tehsildar in Indapur tehsil of Pune. Despite directions from the SDM to act against illegal sand mining in the Bhima and Nira rivers, Yewale allegedly took no action.

The whistleblower

The first signs of alerts in this scam were raised not from government offices, but from a local social worker. Dinesh Kotkar, who also works in real estate, was the first to discover the questionable sale deed.

Kotkar, who runs an organisation named Chhava Kamgar Union, told Newslaundry that about a week after the registration, he received a copy of the original Index-II on WhatsApp. “I immediately went to the Joint District Registrar (JDR) and Stamp Duty Collector Santosh Hingane and asked how such a sale could take place, especially when stamp duty worth Rs 21 crore had been waived. Hingane brushed it off, saying everything was in order.”

Unsatisfied, Kotkar sent two written complaints to Hingane in the month of June, urging an inquiry, he claimed. “He didn’t act on either of them,” Kotkar said. “Then in July, when I was at the Collector’s office, a man named Chitnis came up to me and asked why I was complaining about the sale deed. He didn’t mention his full name, just introduced himself as Chitnis. He said, ‘We’ll request you four or five times to withdraw your complaint otherwise we will handle it our way.’ It was a clear threat, but thankfully nothing happened.”

What makes the case even more curious, Kotkar added, is that the same officer – JDR Santosh Hingane – whom he had alerted later became the complainant in the FIR filed against sub-registrar Ravindra, real estate developer Taru Tejwani and Digvijay Patil, representing Parth Pawar’s firm.

“It’s ironic. Hingane himself was informed by me in May and June, yet he took no action. Now he is the complainant in the very FIR that mentions my complaint. If anyone should also be named as an accused, it’s him. Making him the complainant is nothing short of a joke.”

When Newslaundry asked Rajendra Muthe, Joint Inspector General of Registration, who is also a part of the inquiry committee, regarding Hingane, he said, “We have started the investigation and we are going to inquire about all the aspects of this case.”

Hingane did not respond to Newslaundry’s requests for comment.

FIRs were filed against Tehsildar Suryakant Yewale, Sub-Registrar Ravindra Taru, real estate developer Sheetal Tejwani, and Digvijay Singh Patil, Parth Pawar's cousin and partner in Amadea Enterprises LLP.

When Newslaundry reached out to Anil Vibhute, Senior Inspector, Bawdhan police station, and asked him about not registering the FIR against Parth Pawar, he didn’t respond.

Newslaundry also reached out to Pune Police Commissioner Amitesh Kumar and Pimpri Chinchwad Police Commissioner Vinay Kumar Chaubey for the reasons to not register the complaint against Pawar. Newslaundry also reached out to Parth Pawar. Their replies will be added to this story once they choose to respond.

Pune-based activist Vijay Kumbhar, who has now written to Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis demanding an independent probe into the case, said, “The chief minister has ordered an inquiry, but many of the officials on the inquiry committee were likely involved in the fraud itself. It’s impossible that a sale deed for land under government possession could have been executed without the involvement of government officials and politicians. They are part of the inquiry committee and they will save each other.”

In times of misinformation, you need news you can trust. We’ve got you covered. Subscribe to Newslaundry and power our work.