Can Delhi shield Hasina without straining ties with Dhaka?

In its initial response, the Ministry of External Affairs has been measured, making it a point to say the verdict has been ‘noted’.

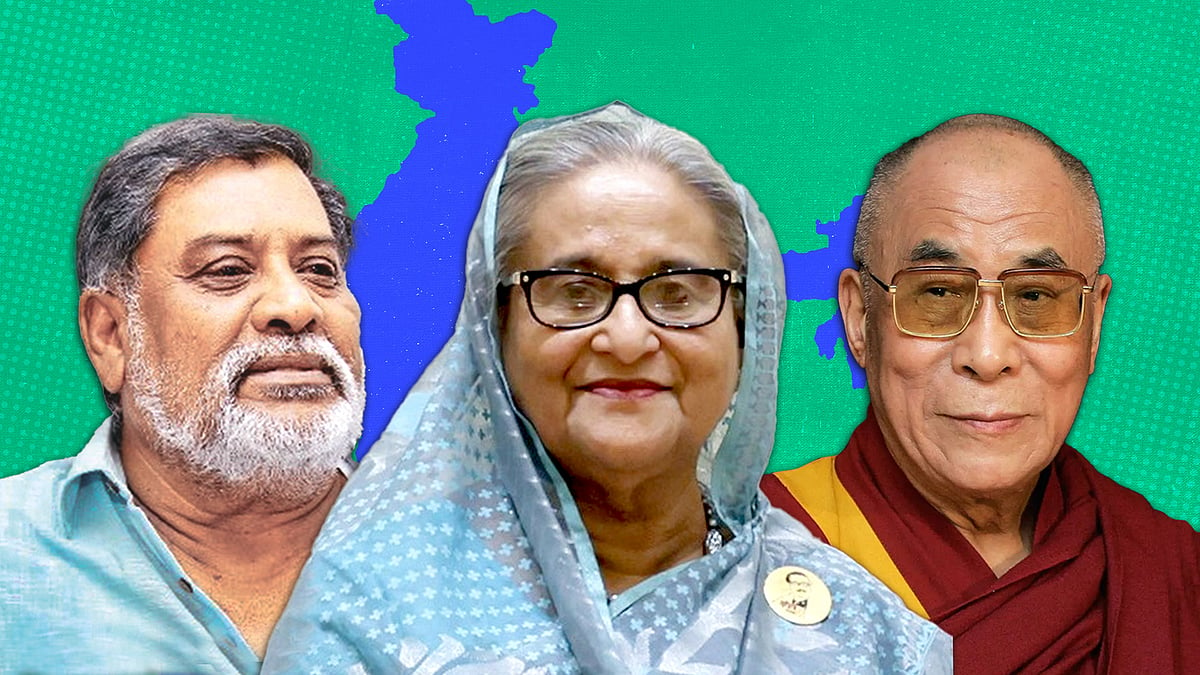

The sentencing of former Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to death by a domestic war crimes court is being seen by many as another episode of vendetta politics in the country. This may set the stage for another spell of political uncertainty in Bangladesh. At the same time, the verdict has implications across the border.

Given the nature of retributive political rivalries in its northeastern neighbour, New Delhi hasn’t been exactly surprised by the verdict. But after anticipating it, India must now navigate the situation with a range of diplomatic options at hand. In the process, New Delhi would also like to carefully attend to its twin imperatives of sheltering Sheikh Hasina as an “honoured guest” and managing core interests in bilateral ties with Dhaka.

In its initial response, the Ministry of External Affairs has been measured, making it a point to say the verdict has been “noted”, and adding that New Delhi is willing to “work constructively” with all stakeholders. In doing so, the MEA also identified its commitment to peace, democracy, and stability in Bangladesh as cornerstones of its course of action. Even such a restrained response leaves something to be read between the lines.

In saying “noted”, New Delhi has avoided conveying “respected” and thus seems non-committal on where it stands on the legitimacy of the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) and its proceedings that gave the death sentence to Sheikh Hasina. By mentioning “all stakeholders”, India is seemingly identifying parties other than the Bangladeshi state as legitimate voices to be considered. That implies that the former prime minister’s side also finds a place in New Delhi’s assessment of the verdict. Finally, by reiterating the principle of democracy and peace as a yardstick, New Delhi might be signalling the need to examine the verdict through the prism of due process and democratic principles. Is that a subtle way of scrutinising the legitimacy of the court’s verdict and the process followed to arrive at it?

The alacrity with which the ICT delivered the verdict has already raised eyebrows the world over, though it is not unexpected in Bangladesh. In the past, the country has seen political rivals – both Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League and Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party – take sharply vindictive steps when they were in power. The subversion of the legal process seems to be following a similar script in the Mohammad Yunus-led interim regime.

The diplomatic community in New Delhi has sensed a form of judicial revenge in the verdict. This includes old Bangladesh hands like Veena Sikri, who served as India’s High Commissioner to Dhaka (2003–2006), as she viewed the tribunal as “nothing but a kangaroo court”. Ironically, the ICT was established by Sheikh Hasina herself in 2009 with the aim of prosecuting those who committed war crimes in Bangladesh’s liberation war of 1971. After 16 years, the same court has given her a death sentence for ordering the use of lethal force against students protesting against her government – an agitation that snowballed into her ouster from power last year.

The immediate question before New Delhi is how to navigate its options when Dhaka’s demand for the extradition of Sheikh Hasina arrives as a formal request from the Bangladeshi government. There are also reports that Dhaka may seek the help of Interpol in bringing the former prime minister back to her country. Dhaka may cite the 2013 mutual extradition treaty signed between India and Bangladesh to ask India to assist in the return of Hasina, who has been in self-exile in India since August 2014. But when the formal request comes, New Delhi has a range of options to examine and decide upon.

First, India can legally decline to extradite Hasina under the terms of its bilateral extradition treaty with Bangladesh. Article 8 of the treaty includes a clause that allows refusal if a request is not made in “good faith, in the interests of justice”. Indian authorities could argue that the charges are politically motivated or not consistent with treaty obligations, thereby rejecting Dhaka’s demand on legal grounds.

Second, instead of saying a firm “yes” or “no”, New Delhi can buy time by engaging diplomatically without making immediate legal commitments. As some procedural formalities are reportedly still being completed, India could use this window to negotiate, request further documentation, or condition its response on other diplomatic or institutional guarantees.

Third, once a formal request is made, Hasina (or India on her behalf) has the right to legally contest it in Indian courts. By doing so, India could delay the extradition process significantly, arguing issues such as potential persecution, lack of due process, or that the request violates principles of justice. Indian media reporting suggests this is a viable path.

Fourth, as a last resort, there is also a drastic option available: India could invoke a clause in the treaty (or its amended version) allowing for termination of the treaty. If India formally withdraws, it could argue that current political conditions make the treaty untenable. This, however, entails diplomatic costs and would require a careful assessment of the cost–benefit calculus if the situation arises.

Even if these options may give India a way around the crisis, New Delhi would also want to ensure that its core interests in ties with Bangladesh remain unharmed. For India, Bangladesh is not just a neighbour but a critical partner for security, connectivity, and trade. Over the past fifteen years, cooperation deepened because Dhaka ensured its territory was not used against India’s interests. Hasina’s government was central to that reciprocity.

A destabilised Bangladesh could influence migration flows, undermine border security, and strain trade routes — a situation that would not serve New Delhi’s interests. So, along with honouring commitments to Sheikh Hasina, India would also like to find a way to work with the current regime in Dhaka. A stable Bangladesh aligns with India’s core interests. At the same time, India cannot look away from the perils of judicial persecution scripting another round of dangerous polarisation in its northeastern neighbour.

If the government can hike print ad rates by 26 percent, we can drop our subscription prices by 26 percent. Grab the offer and power journalism that doesn’t depend on advertisers.

‘Travesty of justice’, ‘Revenge trial’ : Editorials on Sheikh Hasina's death sentence verdict

‘Travesty of justice’, ‘Revenge trial’ : Editorials on Sheikh Hasina's death sentence verdict India’s history of providing refuge – and why Sheikh Hasina poses a unique challenge

India’s history of providing refuge – and why Sheikh Hasina poses a unique challenge