Did ‘Yadav pride’ songs galvanise support for the NDA in Bihar?

Following a party meeting, the RJD said it will issue legal notices to anyone who has spread casteism or demeaned specific communities during the election campaign.

After a post-mortem on its Bihar assembly poll performance, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) has decided to crack down on the booming ecosystem of election-time music. On Saturday, the party said it will send legal notices to singers and creators who used RJD flags, symbols or leader names in their songs without permission. It also warned of action against those who invoked its leadership to push caste-pride messaging or denigrate other communities.

Speaking to Newslaundry, RJD spokesperson Priyanka Bharti said, "The RJD will send notices to all singers who have used party flags or party symbols, or taken the names of leaders without consulting the party leadership. Additionally, the RJD will send notices to those who have used leadership names to spread casteism or demean specific communities."

This statement comes at a time when questions have been raised about the proliferation of Yadav caste-pride songs during the campaign trail, which some political commentators believe may have hurt the party's election prospects.

The proliferation of these caste pride songs is something Prime Minister Narendra made note of during the campaign trail. At an election rally on November 7 in Bhabua in Bihar’s Kaimur district, Prime Minister Modi referenced a couple of lines from Bhojpuri songs invoking Yadav caste pride.

“Marab sixer ke 6 goli chhati me, power hola khali e Ahir jati mai re (We will hit six bullets to the chest like a sixer, this power resides only in the Yadav community.)

Bhaiyya ki sarkar, banenge rangdaar (If it is [Tejashwi Yadav] brother’s government, we will become rowdy.)

Bhaiyya ke aave de satta, katta satake utha leb ghar se (Let [Tejashwi] brother return to power, we will pick you from your house at gunpoint.)

These songs were not commissioned by the Tejashwi Yadav-led RJD. Composed independently by creators and supporters from the Yadav community, they were circulated at gatherings of party supporters and turned into reels to engage a young Yadav audience.

Modi linked these songs directly to invoke Tejashwi’s father, Lalu Prasad, and mother, Rabri Devi’s “Jungle Raj” era (1990-2005). Tejashwi had tried to distance himself from his father's era during the campaign. He pitched a bold, forward-looking vision for Bihar, promising a revolutionary shift like “har ghar rojgar" (jobs for every house), an end to migration, stronger law and order, improved education, industrial infrastructure, youthful leadership and inclusive representation across all castes.

But just when he seemed to be winning over young voters across the state, these controversial caste-pride Bhojpuri songs resurfaced. Designed to rally the core base, the songs revived the ghosts of the "Jungle Raj" era. By celebrating dominance and promoting an exclusionary tone, they reminded many voters of that era.

RJD spokesperson Bharti agreed that such cultural discourse carried a political and social impact. She argued that such songs have been made for the governing NDA as well to woo voters from other communities, but that they should still be stopped. “The party officially does not get these music videos made, but it certainly hampers our image. Such songs are dangerous for society,” she said.

The RJD won 25 of the 143 seats it contested, and secured 23 percent of the vote share – the highest by any party in Bihar – but failed to convert that into seats. It was a slight dip from the 23.11 per cent vote share it received in 2020, when it had won 75 seats.

Are songs the reason?

Senior journalist Umesh Rai wasn’t sure of the scale at which these songs impacted the RJD’s seat tally. However, he said, “When such songs are made, it implies that if this candidate wins, their supporters will enjoy dabdaba (dominance). Over the years, Dalits and the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) have been at the receiving end of RJD supporters’ dabdaba. NDA hopped on it and drove the ‘Jungle Raj’ narrative more than their vikas (progress) pitch. These songs acted as fuel in the campaign rallies.”

Dalit leader Shyam Rajak, who was earlier with the RJD but is now with Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United), said it was “RJD’s culture” to campaign on such songs and threaten voters. “People cannot forget the days of ‘Jungle Raj’ so easily. It is a wound which cannot be healed.”

While it’s difficult to say for sure whether these songs had a tangible impact on the vast and politically decisive bloc of the Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs), often considered swing voters in the state, senior journalist and author Santosh Singh believes that these songs hugely dented the RJD’s vote share. “The Yadav aggression displayed in these music videos has eventually led to the EBCs and non-Yadav castes drifting away from the laalten (poll symbol of RJD),” he said.

EBCs, or the Ati Pichhada communities, comprise 112 castes among the most marginalised OBCs in Bihar. According to the 2023 Bihar caste survey, they account for over 36 percent of the state’s 13.07 crore population and are considered a floating vote base.

“The RJD's core political challenge lies in the fear instilled by its own cultural messaging. The aggressive tenor of their Bhojpuri campaign songs, coupled with the visual assertion of community identity, such as supporters wielding green gamchhas, has unfortunately deepened the apprehension among non-Yadav communities,” Singh said.

Singh also argued that since the early 2000s, the RJD strategically shifted from being the undisputed ‘gareeb ke neta’ (leader of the poor) to becoming predominantly the ‘Yadav ke neta’ (leader of the Yadavs), adding that this narrowing of focus, and the aggression associated with it, actively ensured that other communities remain alienated.

“The RJD cannot maximise its electoral potential until it moves beyond its core base and genuinely takes non-Yadav voters into confidence, winning them over ‘dil se’ (from the heart)," he said.

The results could possibly add credence to these claims. Of the 12 EBC candidates the RJD fielded across the state, only 2 won. The 10 who lost had an average margin of defeat of 27,506 votes. Of the five EBC candidates fielded by Congress – an ally of RJD in the state – only one from Forbesganj in Araria district managed to win by just 221 votes. The average margin of defeat for the other four candidates who lost was 36,652 votes.

EBCs are considered a community that plays the role of a kingmaker in Bihar politics owing to their numerical strength and fragmented identity. In 2015, when Nitish Kumar joined hands with the RJD, he brought the EBCs and Yadavs together for a decisive win with 178 seats. In 2017, when he returned to the NDA, it jolted the Mahagathbandhan. In 2020, nearly 58 percent of the EBCs supported the NDA, giving them 125 seats, over the Mahagatbandhan’s 110 seats.

Kartikeya Batra, Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University and Visiting Fellow at CVoter Foundation, argued that Nitish Kumar carefully cultivated the EBC votebank since 2005.

“EBCs hesitate in letting the Yadavs come to power. Mallahs (Nishads) form 2.6 percent of the EBC community and were expected to vote for Mukesh Sahni’s Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP). Even if the men had become fond of the Mahagathbandhan, the women in the same households still favoured the NDA, particularly Nitish,” he said.

It’s a sentiment that Santosh Sahini, VIP chief Mukesh Sahni’s brother, who was about to contest elections from Gaura Bauram seat, but withdrew his candidature to extend support to the RJD, also maintained. He told Newslaundry that women EBC voters voted in large numbers for the NDA. “Our alliance got EBC votes but not enough to win,” he said.

Amitabh Tiwari, founder of Vote Vibe and political analyst, said that for EBCs, law and order is a big issue.

“They have traditionally voted for the NDA. This time too, the trend continued even though VIP and Indian Inclusive Party (IIP) were on the Mahagathbandhan side. The songs used in RJD campaign rallies certainly backfired for the opposition alliance,” he said.

If the government can hike print ad rates by 26 percent, we can drop our subscription prices by 26 percent. Grab the offer and power journalism that doesn’t depend on advertisers.

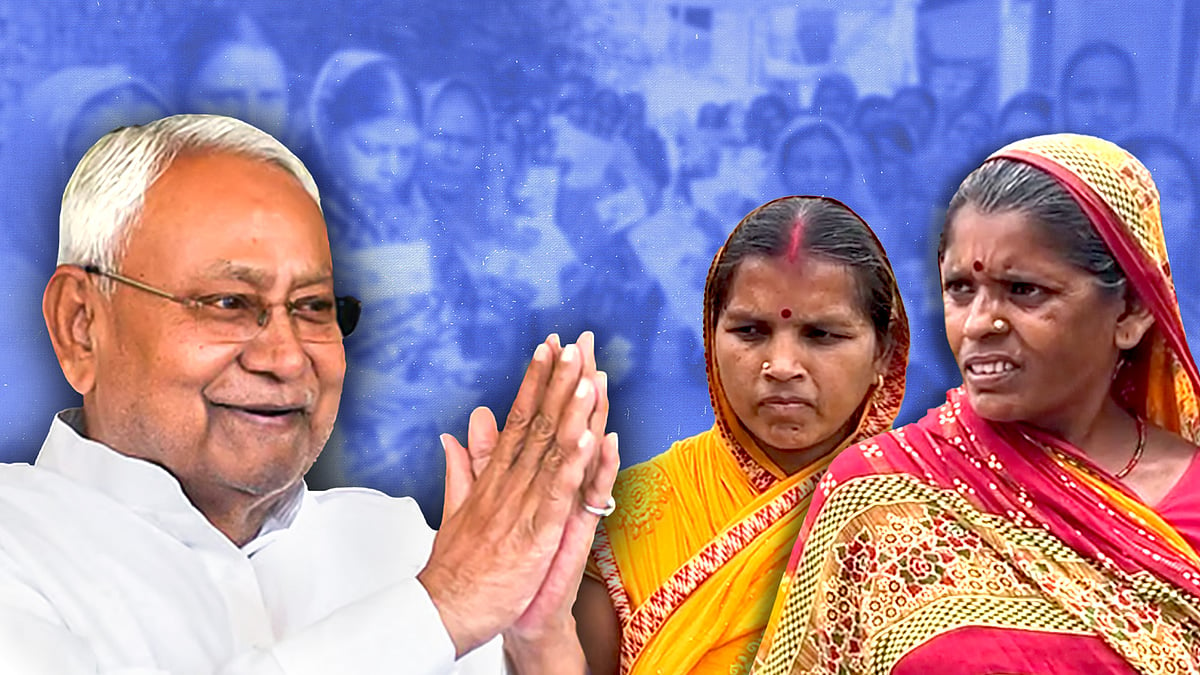

Bihar 2025: Women trust Nitish’s delivery over Mahagathbandhan’s promises

Bihar 2025: Women trust Nitish’s delivery over Mahagathbandhan’s promises Bihar’s verdict: Why people chose familiar failures over unknown risks

Bihar’s verdict: Why people chose familiar failures over unknown risks