Press Club of India elections: Battle to reassert ‘democratic-secular values’ vs RSS influence

Over the past decade, the PCI claims that it has pushed back against what members call government-backed attempts to influence or even take over the institution.

“We will not succumb to this attack. Today, the world should know what Hindustan is doing to Kashmir. The world should know that this is Modi’s India, not Gandhi’s,” declared Sheikh Abdul Rashid – then an independent MLA, today a sitting MP – his voice steady even as black ink and oil dripped from his clothes. Moments earlier, a Hindu fringe group had hurled the mixture at him outside the Press Club of India, enraged by his criticism of the government.

Rashid had just concluded a press conference where he accused the Centre of “dividing the country on religious lines” and spotlighted two Kashmiri truck drivers attacked in Udhampur, whose relatives he had brought to Delhi.

It was October 19, 2015 – a date that has since become part of the Press Club of India’s lore.

The incident underscored how the club, reasserting its 'democratic-secular' bearings under left-liberal executive committees after a faction-controlled era through the 2000s, had remained a rare safe space for anti-establishment voices and for protesting attacks on press freedom.

A sanctuary for dissent

Over the past decade and a half, the Press Club has repeatedly positioned itself against what its members describe as alleged attempts by the government or its supporters to influence, or even take over, the institution. This defensive posture has become central to the club’s image.

As the club heads into its annual elections on December 13, that sense of vigilance dominates conversations among its left members. For many of them, the election is not merely about choosing new office-bearers but about preserving the club’s character as a democratic, secular space.

Any individual or collective challenge to the entrenched left-liberal “syndicate,” critics say, is interpreted internally as part of a broader design by the Narendra Modi government to capture or neutralise the institution. Even suggestions that the club should more actively promote journalism through fellowships draw sharp reaction.

A familiar election script – with fewer challengers

Like in the last two years, challengers to the left-liberal unity are scarce. Two office-bearers – joint secretary and treasurer – have already been elected unopposed. About 4,500 members of the press are eligible to vote for a president, vice-president, secretary general, joint secretary, treasurer and 16 members of the managing committee. This year, 32 candidates are contesting 21 posts – a stark contrast to the 63 who stood in 2022, when it was a full-fledged panel-versus-panel showdown.

The left-liberal alliance, victorious for nearly fifteen years, is widely expected to retain power. Leading the panel, freelance journalist Sangeeta Barroah Pisharoty is fighting for the president’s post; Google News Initiative trainer Jatin Gandhi for vice-president; independent journalist Afzal Imam for secretary general; visual journalist PR Sunil for joint secretary; and NDTV’s Aditi Rajput for treasurer. Sunil and Rajput have already been elected unopposed.

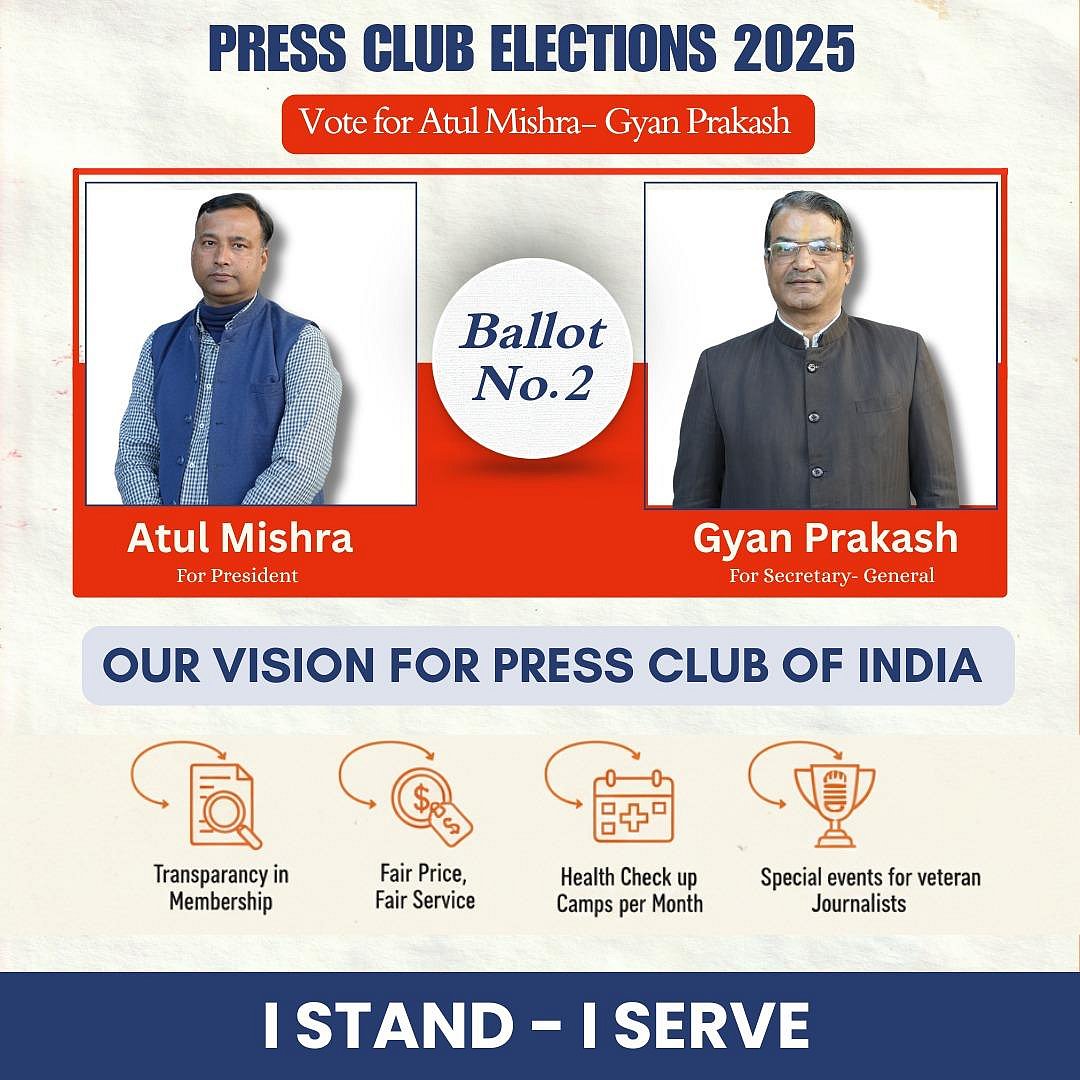

For the president’s post, the contest is three-cornered: Barroah faces veteran journalist Arun Sharma and freelance journalist Atul Mishra. Both men had contested unsuccessfully last year as well. Sharma is the owner of Madhya Pradesh-based Aditya Express daily. He has teamed up with Delhi-based editor of the Rajawat Times, Prahlad Singh Rajput, who is contesting the vice-president’s post against Gandhi and Virender Prasad Saini, a journalist with the fortnightly magazine Jan Bhawana. The Rajput-Sharma camp has promised to reduce the menu rate, provide insurance for members, hold elections using EVMs, and organise mental health camps.

While no rival panel has emerged, a handful of independent candidates have thrown their hats in the ring. Among them is Gyan Prakash, contesting for secretary general. Soon after candidates were announced, photographs of him in RSS uniform began circulating within the club. Prakash confirmed his affiliation without hesitation.

“Yes, I am an RSS swayamsevak. I regularly attend shakhas. There is nothing to hide,” the Rashtriya Sahara journalist told Newslaundry.

Caravan journalist Dhirendra Jha, known for his work on the RSS, called Prakash’s candidature “outrageous”. “A militia group has no place in a democratic space. Why is it putting up its candidate here?” Jha remarked, referring to the RSS, the ideological parent of the BJP.

Some members believe the BJP-RSS machinery, unable to break the left-liberal unity with a full panel, is now attempting a “backdoor entry” by targeting key posts – especially the secretary general, who also functions as the club’s CEO.

Prakash rejected the claims: “They are lying and spreading rumours.”

“It’s not a full-fledged robbery but an attempt to breach the club,” observed former secretary general Nadeem Kazmi, who had come from Bihar to support his colleagues. He said overconfidence may lead to lower voter turnout among left-liberal supporters.

“We have to be vigilant as they have a fixed vote bank of 300-400 votes,” said Kazmi. In previous years, the turnout has remained between 40% and 50%.

In a video message, BJP MLA Satish Upadhyay appeared alongside Gyan Prakash and Atul Mishra, wishing them success.

“They have been very active in the press club. I wish them a bright future,” he said.

Campaign styles and promises

Barroah, the outgoing vice-president, highlighted her panel’s achievements over the past year, which include drafting a media bill, setting up a studio, consistently opposing the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, supporting two journalists from Madhya Pradesh who alleged custodial torture, and organising a literature festival, discussions, and workshops. She also said PCI collaborated with press bodies from other states for advocacy against the DPDP Act.

She said the club issued a “record number of statements” on press freedom this year. “In Delhi, we may think such statements don’t matter much. But they help journalists under attack in smaller towns,” Barroah argued, pledging to deepen the club’s commitment to media freedom.

She said the club has been constantly in touch with several opposition MPs who can take the Media Transparency (and Accountability) Bill to Parliament.

Her panel’s manifesto includes training workshops, cultural programmes, legal support for journalists, and expansion of the club’s legal cell. Afzal, meanwhile, underlined that the club is the only place where even anganwadi workers could raise their issues.

Meanwhile, the opposing Prakash-Mishra camp promises to reduce prices at the club, ensure transparency in new membership, introduce monthly health camps, and host special events for senior journalists.

‘Doesn’t feel like election week’

Except for newly installed entrance tiles and privacy screens atop the boundary wall, there is little that indicates that election week is in full swing at the club. Only the Barroah panel actively circulated pamphlets this week, moving from table to table.

Meanwhile, the Prakash-Mishra duo mostly remained seated, interacting with visitors. “Our way of campaigning is different. We do it one-on-one,” Prakash said.

Both panels have been visiting media offices – PTI, IANS and others – to solicit votes.

Mishra accused the left of running the club like a “syndicate” for the last 10-15 years through a revolving leadership. Outgoing president Gautam Lahiri, elected four times in 2016, 2017, 2023 and 2024, declined to speak with Newslaundry.

As per the club’s constitution, a member can hold office for a maximum of two consecutive terms. They can contest again after a gap of two years. At least six members of the current left-liberal panel have served in the current or previous executive committees in various roles.

“Everyone knows who’s going to win. That’s why it’s a no-contest,” a member remarked on condition of anonymity.

Another said the revolving door is due to a lack of journalists willing to take up the challenge. “They have to attend club meetings and perform various functions. We have to give it to them that at least they are ready to devote their time to the club,” the member said.

Some members revived an old demand: instituting a PCI journalism award akin to the Mumbai Press Club’s Red Ink Awards. Since 2021, this promise has not been mentioned in the manifestos. Others pushed for fellowships for journalists – a suggestion that would soon trigger a public spat.

The fellowship flashpoint

Founded in 1957, the PCI operates as a Section 8 company under the Companies Act, meaning profits must be reinvested and cannot be distributed among members.

Ahead of the polls, The Reporters’ Collective co-founder Nitin Sethi suggested on X that the club allocate Rs 50 lakh – about 5% of its food and liquor revenue – to fund fellowships for disadvantaged journalists. “This is the least PCI must do to claim its position as a representative body fostering journalism in India,” he argued, citing the club’s revenue figures.

The club fired back a day later, accusing Sethi of “spreading disinformation”.

“He highlighted gross income without disclosing expenditure,” the club said in a statement posted on their X account. PCI revealed its expenses were Rs 11.34 crore in FY 2024–25 and Rs 10.90 crore the year before, against revenues of Rs 11.59 crore and Rs 11.08 crore. Profits stood at Rs 25.37 lakh and Rs 17.25 lakh in those two years.

Sethi retorted that the PCI statement sounded like that of “aggrieved friends, not an institution”.

Another contentious issue was the club’s liquor inventory. PCI recorded liquor stock worth Rs 76 lakh at the end of 2023–24, rising to Rs 1.01 crore the following year. Sethi argued that since supplies in Delhi arrive weekly, the club need not lock up such sums.

“Freeing up Rs 30+ lakh would allow immediate investment in journalism,” he said.

While the exchange dominated club chatter, several members welcomed Sethi’s proposal. “Why reject the idea outright? At least start somewhere,” a journalist from an English daily remarked.

But a member aligned with the left countered: “The club does not have the financial headroom. And if we take money from businessmen, we’ll have to follow their orders. At a time when we are fighting the Modi government on all fronts, we cannot be open to outside influence.”

The first quarter of the century is coming to an end – a period that’s changed everything about technology, politics and the press. Make it count by supporting reporting that still puts truth first.

Govt is ‘judge, jury, and executioner’ with new digital rules, says Press Club of India

Govt is ‘judge, jury, and executioner’ with new digital rules, says Press Club of India Press bodies condemn FIR against Mahesh Langa, seek PCI intervention

Press bodies condemn FIR against Mahesh Langa, seek PCI intervention