TV media sinks lower as independent media offers glimmer of hope in 2025

Mainstream TV media’s coverage of Operation Sindoor and the Delhi blasts failed to abide by even the basic norms of journalism.

As we come to the end of 2025, how do we assess the state of our mainstream media? Can it sink lower than it already has, given that it stands at 151 out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index?

It can because in more than two instances this year, mainstream media, especially TV news, has demonstrated the depths to which it can fall.

Yet there is a glimmer of hope: despite the dismal performance of mainstream TV channels, independent journalists and digital platforms still survive and do the kind of journalism this country needs.

The two lowest points for our mainstream media this year, in my view, were the coverage of Operation Sindoor and the reporting and follow-up stories after the Delhi blast, when a car exploded at peak hour near the Red Fort, killing an estimated 15 people.

Indian TV channels love war and conflict. It allows them to dramatise, increase decibel levels, and stage the conflict in their studios by pitching individuals who can outshout their opponents. But the coverage of Operation Sindoor exceeded expectations.

Indian channels, even so-called “respectable” news channels like India Today, fell for the fake news that India had captured Lahore and bombed Karachi. In the rush to be the first, these channels fell hook, line and sinker for the most obvious fake news. Even a slight pause, a pinch of scepticism, and taking time to implement a basic journalistic norm – verify and double check – would have saved them from this stupid and appalling faux pas. But no, who has the time these days to do this? Scepticism is reserved for statements made by those who oppose the government, while obedience to the narrative of those who support it is the norm.

Just watch this episode of TV Newsance by Manisha Pande to remind yourself of the disgraceful coverage by our leading TV news channels. It is cringeworthy.

In fact, Rajdeep Sardesai, one of the many anchors who allowed these fairy tales to be broadcast as if they were verified news, acknowledges that it was a mistake and says he apologised on air. A long profile piece on him in Caravan mentions that in a post-mortem bureau meeting, when asked why they didn’t verify the news, India Today staffers said that several reporters had been called by ministers and senior officials from various ministries telling them that this was precisely what was going to happen and that TV channels should “break” this news.

The media’s behaviour during Operation Sindoor reconfirms what’s now well known: that the government briefs journalists through messages and phone calls about what should be reported.

The other low point in my view is the way the media reported the Delhi blast and its aftermath. All kinds of unverified information were instantly broadcast and reported. Basically, anything the government or investigative agencies told the media was presented as the truth, with no effort at fact-checking (read here).

A consequence of such reporting was felt immediately by ordinary Kashmiris in other parts of the country and in Kashmir. The demolition of the house of the main suspect was reported but not questioned; the fact that all doctors from Kashmir were being viewed as potential suspects was also not questioned.

And if this was not enough, the locked office of the Kashmir Times in Jammu was raided by the State Investigation Agency, which claimed it had found guns and ammunition in it. The editors and owners of the paper, which is now published remotely as a digital publication, have been charged under various sections, including for violating India’s “sovereignty”. Kashmir Times is practically the only independent voice coming out of Kashmir, as most others have either fallen in line or been banned.

The state of the media in Kashmir, and the problems that journalists there face almost every day, continues to be the litmus test for the extent of freedom that the Indian media enjoys. Just this week, the police arrived at the home of Jehangir Ali, the reporter for The Wire, and without a warrant, seized his phone without providing him with the hash value to ensure that it would not be tampered with. He finally got the phone back after several hours.

A glimmer of hope

Despite the Modi government's proactive efforts to ensure that mainstream media sticks to the approved narrative, and the threats and intimidation, especially against journalists in Kashmir, aimed at sending a clear message to other journalists who choose to do their jobs, several remarkable investigative stories have appeared on independent platforms.

At a time when the word “environment” is clubbed with the killer air pollution levels in Delhi and in many other cities in India, it is important to remember that there are other pressing environmental challenges that get precious little coverage in the media, such as the handing over of forests to private interests.

A story to note is independent journalist M. Rajshekhar's piece on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Writing in Time magazine, Rajshekhar reports on the disaster that the natural resources of the islands and the indigenous communities face due to the government’s policies.

Another story that stands out for the challenge the reporter must have faced while investigating it is Nidhi Suresh's report in The News Minute. The journalist did a remarkable job by talking to the nun who alleged she was raped by Bishop Franco Mulakkal in 2018. Although the Bishop was acquitted, no one knows what happened to the nun. Nidhi Suresh traced her and persuaded her to speak. The result is a chilling narrative in 10 parts of the life of this woman.

Another recent investigative story is Sukanya Shantha's three-part series in The Wire. Based on publicly available data, Shantha has followed up on the National Investigation Agency’s claims that it secured convictions in 100 percent of its cases in 2024. Her digging revealed that this was happening because the people accused, the majority of them Muslim men charged under laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), were persuaded to plead guilty when faced with the reality that they would spend much longer in jail as undertrials waiting for the trial to begin.

While Alt News remains outstanding in its fact-checking work, as seen best during Operation Sindoor, Newslaundry has also done notable stories, like this one on the stampede during the Kumbh Mela this year. The government insisted that only 30 people had died. NL reporters, however, found that as many as 79 had died in the stampede. This was established by doing the kind of routine work that journalists are expected to do: first being sceptical of government data, then following up and checking for yourself. When that is done, as we saw during the Covid pandemic, there’s always a yawning gap between official figures and reality.

While “vote chori” and elections continue to be widely covered, the back story of how political parties like the BJP are funded, particularly before the Supreme Court scrapped the Electoral bonds scheme, did not get the same kind of attention.

Although Indian Express has now done a detailed story on who funds political parties, earlier it was independent platforms that investigated the Electoral Bonds scheme. More recently, the Reporters’ Collective has investigated the BJP's funding in Assam. The results are revealing. Most of the funders are people who have won lucrative government contracts.

And finally, like Kashmir, some of the best reporting on Northeast India, which only comes into focus during conflict, is from reporters working for independent digital news platforms. Like this report by Rokibuz Zaman of Scroll of the people physically pushed out of Assam into Bangladesh because they were suspected to be “foreigners” even though they were Indian citizens.

In sum, at the end of 2025, we are where we were at the end of 2024. The mainstream media houses, and specifically their television channels, continue to compete to go lower with news that is sometimes untrue and almost always divisive in a country where the nature of our politics increasingly fractures the polity.

And for real journalism, for in-depth stories, practically the only source – although some print media like Indian Express, The Hindu and Times of India have done some excellent long-form stories – are the independent digital news platforms that continue to survive, even if precariously.

The first quarter of the century is coming to an end, and with it 25 years of rising misinformation, shrinking newsrooms and growing corporate control. Make it count by subscribing to NL and TNM so independent journalism can survive the next 25.

When media ‘solves’ terror cases, Kashmiris are collateral damage

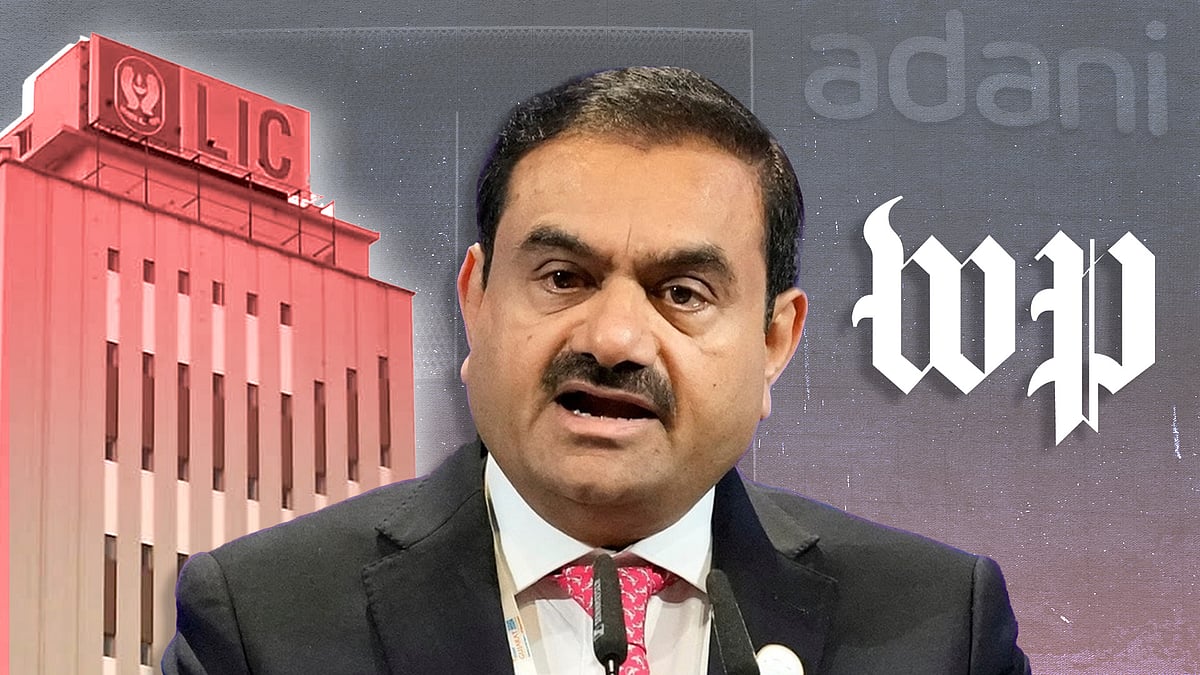

When media ‘solves’ terror cases, Kashmiris are collateral damage Washington Post’s Adani-LIC story fizzled out in India. That says a lot

Washington Post’s Adani-LIC story fizzled out in India. That says a lot