Forget the chaos of 2026. What if we dared to dream of 2036?

Vivek Kaul takes you on a surreal journey of what Mumbai and India can look like in 2036.

Tuesday, January 1, 2036.

It’s a cold January morning in Mumbai – 18 degrees actually – as cold as Mumbai can be. I have just woken up after a refreshing night’s sleep and can hear my young neighbour – who for some reason continues to be obsessed with the 1950s – playing that 1958 Sahir Ludhianvi anthem wo subah kabhi to aayegi (that morning will come someday).

Honestly, that morning has already arrived, and such maudlin, depressing, and pessimistic songs, should be a thing of the past.

I open the windows to my 30th floor one-BHK apartment in Worli, and can see an unending blue sky outside. The sea is sparkling, with a few people out for early morning yachting before the temperature picks up.

I walk into the living room, open the door to the apartment, and pick up the newspaper lying outside. For some reason, newspapers are still going strong. In fact, their readership has grown since 2030, driven by those born in the 21st century who, in an effort to shrink their digital footprint, have turned back to letters on paper rather than words on a screen.

Listening to wo subah kabhi to aayegi leaves me feeling melancholic, just when I want to feel optimistic and get my adrenaline going. I start playing the 2007 Jaideep Sahni anthem Chak De! India to kill the early morning blues and take the day that lies ahead head on.

I whip up an omelette and make myself a cup of black coffee (actually, it’s a pour over). I pick up the newspaper and see an eight-column flyer: India’s per capita income expected to cross $8,000 in 2038.

The country has constantly been growing at greater than 12 percent per year for the last six years. The good thing is that unlike the 2020s, the growth in the 2030s has been more equitable and well spread out, with more households benefitting from it.

India has tackled the ill-effects of artificial intelligence (AI) very well by putting systems in place. Anyone who loses their job to AI, is on unemployment insurance for 18 months. A part of the income tax paid every year is specifically allocated towards this programme. Further, many reskilling programmes have been launched.

On the other extreme, programmes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), which was renamed and relaunched as the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (VB–G RAM G) in 2026, are now more or less a thing of the past, with limited operations in Bihar, eastern Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand.

A quick breakfast and a shower later, I am out on the street with my new ultra-light bicycle. This bicycle is an engineering marvel – if a bicycle can be called one. It’s totally made in India, and costs just Rs 40,000. I start walking towards the bicycle lane on the Annie Beasant road, which is around 300 metres from my building.

In fact, bicycle lanes are now a part of almost every major road in south and central Mumbai. The western and central suburbs should join this bandwagon in a year or two. Mumbaikars have taken to bicycling like fish take to water. This has dramatically brought down the air-pollution in the city.

What has also helped is the fact that after many years of neglect, the Brihanmumbai Electricity Supply and Transport Undertaking is back at running a world class bus system, encouraging many more people to travel using public transport than their private vehicles. Car sales and motorised two-wheeler sales have fallen majorly in the island city.

Even Delhi is trying to implement what is now being called the Mumbai model, but is finding it difficult given that many RWA uncles are still living in denial, and are mentally stuck in what in their heads was the golden era of the 2020s.

Another major reason for the success of the Mumbai model has been the fact that people can now live close to where they work. In international circles, the Mumbai model has been termed as the seven kilometre model, with people living at best seven kilometres from where they work. This allows many to cycle to work.

Crucially, a new Mumbai builder – Niranjan Lodha – showed the world that there is a fortune to be made at the bottom of the pyramid by building reasonably priced smaller apartments. This building technology has been totally made in India. Hence, there has been a proliferation of affordable one-BHK apartments all across the city.

Further, post 2029, the bubble in super-premium housing in the city started to fizzle out, forcing builders to look at actually making homes for people to live-in, than the super-rich to buy and hopefully flip. Real estate has stopped being a financial asset.

Of course, the inheritance tax introduced in 2030 has only helped the cause. Also, the state government has reduced the stamp duty to be paid at the time of buying a home to 3 percent. It now makes up for the lower collections in stamp duty through better collection of property tax.

Continuing to walk, I look up at the sky and see a poster of Housefull 10.

Actor Rajeev Kumar Bhatia is still going strong. But the movie has made a star out of the actor starring opposite Bhatia. I can’t quite recall her name right now. But she is being called the new Gujarat model. Despite this, I continue to maintain that the one and only Gujarat model India has ever had was Parveen Babi.

I reach the bicycle lane, get on to my bicycle, and start cycling towards the Aqua Line metro station. The bicycle I am riding has been one of India’s many technological breakthroughs. This has happened because many IITians who moved out of India in the 1990s and the 2000s, have come back to India, given up on their American citizenships, and have helped unleash a technological revolution in the country. And surprise surprise, this has been funded by venture capitalists.

Through much of the 2020s, the venture capitalists kept splurging money on building quick delivery systems and burned a lot of cash doing so. Ultimately, it perhaps occurred to them that life has to have a little more meaning than just getting things delivered in under 10 minutes.

Sometime in the late 2020s, this very mercantile ecosystem of Indian venture capitalists, decided to start funding slightly long-gestation businesses, which would ultimately build better and cheaper products for people to use.

My bicycle is a result of that. Ludhiana is now the bicycle capital of the world. India now spends close to 4 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on research, up from around 0.6-0.7 percent in the early 2020s. The government spending on education has also grown leaps and bounds.

The venture capitalist funded coaching institutes are gradually going out of business. In fact, one venture capitalist has recently funded a business called bankruptcy wallah – which helps firms to shut down, cheaply and properly.

I have a Mango mobile phone in my pocket. Mango is a venture capitalist funded home grown smartphone brand built by first generation entrepreneurs – okay, okay, not actually first generation – but then facts shouldn’t come in the middle of a good story. Almost 60 percent of Mango is Made in India. But the firm is still dependent on China for the remaining 40 percent. This dependence has been reducing year on year.

Indeed, the Make in India plan launched with much fanfare in the 2010s is finally taking off. Why? The economists are still trying to figure out a deeper answer. Nonetheless, I have a good explanation for it – something that can be easily shared on WhatsApp – oh yes, WhatsApp is still around. Their network effect is still going strong.

In 2025, the economist Ha-Joon Chang in an interview to the Frontline magazine, had said that Indian business elites did not want serious industrialisation, primarily because they were either in the financial sector or, even if they were in the industrial sector, they still had very strong links with financial capital which doesn’t like industrialisation because, for them, the most important thing was the rate of return.

And if a serious industrial base has to be built then financial returns – particularly from the stock market – need to take a backseat – at least in the short to medium term. As Chang had explained: “If shareholders keep asking for money [in the form of return on investment], companies would not have the money to invest.”

Somehow this dynamic has changed over the last few years and Indian business people have been investing to help the country industrialise more. Don’t ask me why. Because if I knew I wouldn’t be offering this as an explanation over WhatsApp.

I get into the metro station to take the metro to the Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC), where I have a meeting with someone who works in the business of managing other people’s money (OPM).

I can hear Shammi Narang and Rini Simon Khanna asking the commuters to stand behind the yellow line, as my train enters the platform. For nearly a decade, Narang and Khanna, kept asking the commuters to stand behind the yellow line whenever a train entered the platform. The trouble was there was no yellow line on the platform.

Early this year a yellow line was painted across all Aqua Line metro stations. It took more than a decade, but then all’s well that ends well.

I enter the metro coach and place my bicycle in a space specifically allocated for bicycles. The coach is full of advertisements. There is Juhi See advertising that filmi sitaron ka beauty sabun.

Well, the young have all moved to using a bodywash for bathing. But a set of consumers – aged 60 or more – still prefer the soap. It’s the price point you see. They can’t get themselves to pay Rs 600 for every bottle of bodywash. And Juhi See still reminds them of a time when they were all young.

Of course, the brand also sells bodywash. And that’s advertised by the actor who has been christened the new Gujarat model.

It’s interesting that Juhi See recently tweeted about the dollar crossing Rs 150 on ‘Y’ (the app formerly known as ‘X’). Thankfully, this time, she didn’t make any underwear jokes.

And that reminds me that the man who could have been named Inquilaab Srivastava is still going strong. He continues to number his tweets on ‘Y’. I whip out my Mango smartphone to check. The current number is 8,713. He has slowed down over the years. Oh, surprise, surprise: the last tweet is about the dollar crossing Rs 150.

Of course, this is par for course. The US economy has bounced back in the post Trump years. Trump tried to get himself a third term, but he couldn’t get around the 22nd amendment.

Looking around I also see the recently-retired cricketer Sarfraz advertising a bank. His career took off in the late 2020s after Lord GaGa was finally replaced as the cricket coach of the Indian men’s team.

In 10 minutes I arrive at the BKC metro station. There is an underground tunnel that connects this metro station to the BKC bullet train station. A friend recently took a bullet train to Ahmedabad. As soon as he reached, he was surprised to see advertisements of Woodpecker beer – the queen of good times – all over the city.

Prohibition is now a thing of the past and the state government has been able to earn a lot of tax revenue thanks to this move. The bootleggers have been booted out of the state.

I get out of the station and ride my bike crossing the National Stock Exchange (NSE) along the way. As Indian companies have progressed leaps and bounds, so has NSE.

I meet the OPM wallah at a coffee shop. I order a pour over. He sticks to his matcha latte – not wanting to pay the American coffee chain for basically boiling water and pouring it over some prepackaged coffee. “There has to be some value-add,” he says. He doesn’t like it when I say: “Oh, but matcha is tea not coffee.” I guess the wound still hurts.

In his past life in the 2020s, he used to run a venture capitalist funded coffee chain – four shops in and around the Silk Board junction in Bengaluru – but he liked to think of it as a coffee chain.

But after years of running up losses and lining up his pocket, the venture capitalists funding him finally decided to pull the plug. He then used his MBA degree and the old boys network to move into the OPM business.

His big talking point these days is that the Sensex will touch 20,00,000 points by 2050. It is currently at 2,50,000. This forecast has made him the darling of the stock market and everyone wants to meet him.

He reminds me of an old investor called Ridham Shah, who kept making such predictions from the 1990s to the 2020s. The grapevine tells me they are related. Some things never really change.

I take his leave and am soon cycling back to the BKC metro station. About 200 metres from the station, I see an SUV coming towards me at speed, on the wrong side of the road, and right on the bicycle track. My first thought is that this is what happens when too many Dilliwallahs move to Mumbai.

Pretty soon, I realise that the SUV is not going to stop, and that the light at the end of the tunnel is an oncoming train… It bangs into me… the SUV… not the train… Me and my bicycle go flying into the air… and then I wake up… maybe… perhaps… I don’t know…

Tuesday, January 1, 2036.

I am tossing and turning on my single bed in my studio apartment – which, thanks to all the redevelopment in the city after the pandemic, has become next to impossible to find.

In this city of overachievers, central Mumbai now has many more ghost towers built for the super-rich. They have bought these flats and kept them locked.

The most basic flats in Mumbai now start at Rs 4.99 crore only. The words “crore” and “only” continue to be used one after the other. I guess, time doesn’t kill every irony, or for that matter, makes them easier to bear.

I open the door to my apartment and look out. The winter smog has become permanent. The traffic is honking like it always does, with everyone in a hurry to reach their office, before their bosses use the AI excuse to fire them.

In all this, my 1960s obsessed neighbour, who has been out of work since AI took over his job in the early 2030s, is playing that 1966 Gopal Das Neeraj classic, karvan guzar gaya gubaar dekhte rahe (The caravan passed by, and we kept watching the dust.)

Hope has become a playlist of old Hindi film songs. The future keeps offering itself like the Indian men’s cricket team of the 1980s and the 1990s – glimpses of brilliance, followed by that familiar disappointment – and all that remains is dust, smog, and nostalgia for the good times that perhaps never were.

The question is no longer wo subah kab aayegi (when will that morning come), but whether we will recognise the morning when it does come.

Vivek Kaul is an economic commentator and a writer.

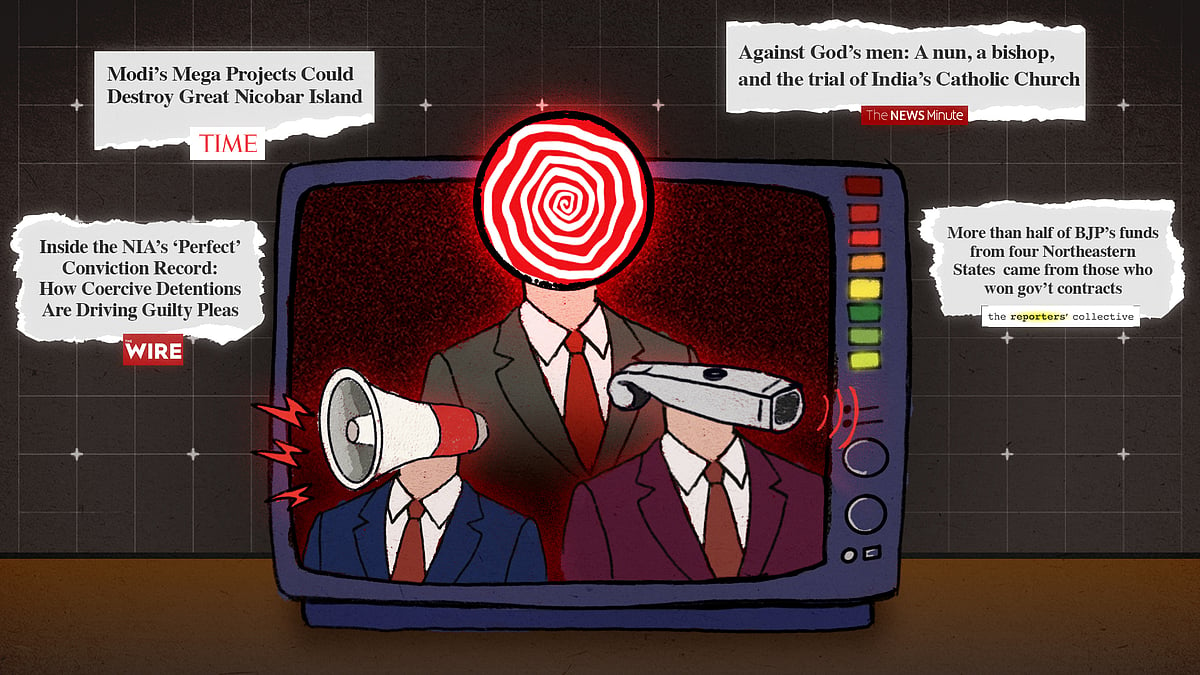

Twenty-five years have transformed how we consume news, but not the core truth that democracy needs a press free from advertisers and power. Mark the moment with a joint NL–TNM subscription and help protect that independence.

Inside Mamdani’s campaign: The story of 2025’s defining election

Inside Mamdani’s campaign: The story of 2025’s defining election TV media sinks lower as independent media offers glimmer of hope in 2025

TV media sinks lower as independent media offers glimmer of hope in 2025