Why India needs Ambedkar’s federal blueprint for the delimitation deadlock

Prioritising federal stability over the ‘obsession’ with gigantic linguistic states, Dr Ambedkar envisioned smaller administrative units to protect minority interests.

In 1976, at the height of the Emergency, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi froze delimitation – the redrawing of parliamentary and assembly constituencies – effectively locking India’s political map in place. The freeze, meant to last until 2001, outlived her government. But decades later, the Narendra Modi government seems determined to do away with the deadlock.

But the proposed exercise has sparked significant concern, particularly among southern states, about the shift toward a new population-based seat distribution. These states argue that using current population figures would unfairly penalise them, reducing their proportional representation despite their success in managing population growth. Leaders across the south warn that this shift could dilute their states’ political influence and threaten federalism.

Meanwhile, there are other consequences for the Modi government too. For example, besides the initiation of the 16th Finance Commission, the fate of the Women’s Reservation Act in parliament and assemblies is deeply tied to the outcomes of delimitation.

Though there’s a data hurdle to the exercise. Constituencies are still based on the 1971 Census, conducted 55 years ago. The upcoming redrawing of electoral boundaries (delimitation) for the Lok Sabha and state assemblies will be guided by the first Census conducted after 2026.

Why the freeze?

In the early stages of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s tenure, her government radically pushed for population control and promised to incentivise states that succeeded in it. In response, the southern states, especially, invested in progressive family planning, birth control, early education, and public health to control their population growth. The northern states, however, could not meet these expectations.

At this juncture, freezing the delimitation task became a political compulsion to ensure that states which performed well in population control were not penalised in terms of political representation in the Lok Sabha, where seat allocation relies heavily on population. The 1971 Census freeze was thus introduced as a temporary federal compromise to protect the Union–state relations.

But what was meant to be a short-term solution has become a puzzle decades later. At this juncture, revisiting Dr B R Ambedkar’s diagnosis could help us understand the federal deadlock he had already anticipated in the 1950s.

A quick walk through history

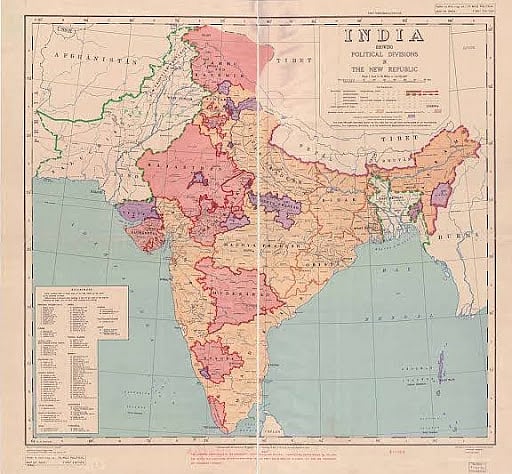

Post-Independence, when the Constitution was coming into force, India’s political map was organised into four administrative categories [Part A, B, C and D] within the Union, as shown below.

Part A comprised the erstwhile British provinces of Assam, Bihar, Bombay, Madhya Pradesh, Madras, Orissa, Punjab, the United Provinces, and West Bengal. Part B states consisted of former princely states such as Hyderabad, Jammu and Kashmir, Madhya Bharat, Mysore, Patiala, East Punjab States Union, Rajasthan, Saurashtra, and Travancore–Cochin. Part C states were primarily former Chief Commissioners’ provinces, namely Ajmer, Bhopal, Bilaspur, Coorg, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Kutch, Manipur, Tripura, and Vindhya Pradesh. In addition, there was Part D – the Andaman and Nicobar Islands – administered directly by the Centre.

At this stage, India faced the profound task of reorganising states, primarily along linguistic lines, in keeping with a long-standing promise of the Congress led by MK Gandhi.

From the 1920s, Gandhi began to make a mark in the freedom struggle. Back then, none of the intellectuals of the day could even fathom that he would convert a largely isolated and elitist Independence struggle into a nationwide mass movement. He used two strategies to pursue this objective: civil disobedience and the introduction of drawing states along linguistic lines. Ambedkar noted that it was the latter one that appealed a lot to the local masses.

In Thoughts on Pakistan, Ambedkar wrote:

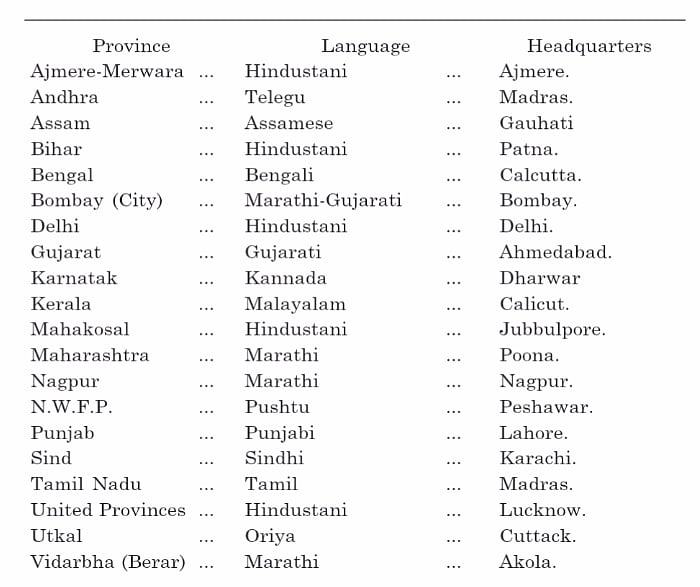

It will be remembered that as soon as Mr. Gandhi captured the Congress, he did two things to popularize it. The first thing he did was to introduce Civil Disobedience… The second thing Mr. Gandhi did was to introduce the principle of Linguistic Provinces. In the constitution that was framed by the Congress under the inspiration and guidance of Mr. Gandhi, India was to be divided into the following Provinces with the language and headquarters as given below:

In this distribution no attention was paid to considerations of area, population or revenue. The thought that every administrative unit must be capable of supporting and supplying a minimum standard of civilized life, for which it must have sufficient area, sufficient population and sufficient revenue, had no place in this scheme of distribution of areas for provincial purposes. The determining factor was language. No thought was given to the possibility that it might introduce a disruptive force in the already loose structure of the Indian social life. The scheme was, no doubt, put forth with the sole object of winning the people to the Congress by appealing to their local patriotism.

This period marked the onset of linguistic consciousness in Indian politics. The idea of organising states along linguistic lines was advanced by Gandhi to meet his political objectives.

Ambedkar expressed his thoughts on the idea of linguistic states, its merits and demerits in his writings in a book titled Thoughts on Linguistic States [1955] [BAWS (Babasaheb Ambedkar writings and speeches) Vol 1]. Commenting on the merits of one state, one language, he wrote:

The reasons why a unilingual State is stable and a multi-lingual State unstable are quite obvious. A State is built on fellow-feeling. What is this fellow-feeling? To state briefly it is a feeling of a corporate sentiment of oneness which makes those who are charged with it feel that they are kith and kin. This feeling is a double-edged feeling. It is at once a feeling of fellowship for one’s own kith and kin and anti-fellowship for those who are not one’s own kith and kin. It is a feeling of “consciousness of kind” which, on the one hand, binds together those who have it so strongly that it over-rides all differences arising out of economic conflicts or social gradations and, on the other, severs them from those who are not of their kind. It is a longing not to belong to any other group… There will be people who would cite the cases of Canada, Switzerland and South Africa. It is true that these cases of bilingual States exist. But it must not be forgotten that the genius of India is quite different from the genius of Canada, Switzerland and South Africa. The genius of India is to divide-the genius of Switzerland, South Africa and Canada is to unite.

While writing on the demerits of linguistic states, he noted:

A linguistic State with its regional language as its official language may easily develop into an independent nationality. The road between an independent nationality and an independent State is very narrow. If this happens, India will cease to be [the] Modern India we have and will become the medieval India consisting of a variety of States indulging in rivalry and warfare. This danger is of course inherent in the creation of linguistic States. There is equal danger in not having linguistic States. The former danger a wise and firm statesman can avert. But the dangers of a mixed State are greater and beyond the control of a statesman however eminent.

While articulating his fears of linguistic states, Ambedkar wrote in an article for the Times of India on April 23, 1953, headlined, Need for Checks and Balances:

In a linguistic State what would remain for the smaller communities to look to? Can they hope to be elected to the Legislature? Can they hope to maintain a place in the State service? Can they expect any attention to their economic betterment? In these circumstances, the creation of a linguistic State means the handing over of Swaraj to a communal majority. What an end to Mr. Gandhi’s Swaraj! Those who cannot understand this aspect of the problem would understand it better if instead of speaking in terms of linguistic State we spoke of a Jat State, a Reddy State or a Maratha State.

Ambedkar’s warnings on India’s federal future

Ambedkar’s warning on the existing federation stands self-evident. He warned that the consolidation of the north into large states and the balkanisation of the south would result in one’s political dominance over the other. This is evident as the saying goes in Hindi – “Delhi ka rasta Lucknow se jaata hai” (The road to Delhi goes through Lucknow).

Ambedkar warned that such an imbalance could eventually lead to a civil war, drawing a parallel with the United States, where a similar conflict culminated in a civil war.

In Thoughts on Linguistic States, he said:

What the Commission has created is not a mere disparity between the States by leaving UP and Bihar as they are, by adding to them a new and a bigger Madhya Pradesh with Rajasthan it creates a new problem of North versus South.

The North is Hindi speaking. The South is non-Hindi speaking. Most people do not know what is the size of the Hindi-speaking population. It is as much as 48 percent of the total population of India. Fixing one's eye on this fact one cannot fail to say that the Commission's effort will result in the consolidation of the North and the balkanization of the South…

Can the South tolerate the dominance of the North?... It must not be forgotten that there was a civil war in the USA between the North and the South. There may also be a civil war between the North and the South in India. Time will supply many grounds for such a conflict. It must not be forgotten that there is a vast cultural difference between the North and the South and cultural differences are very combustible. In creating this consolidation of the North and balkanization of the South the Commission did not realize that they were dealing with a political and not a merely linguistic problem. It would be most unstatesmanlike not to take steps right now to prevent such a thing happening.

His remedies

One of his most critical remedies was regarding parliamentary representation. He suggested that every state should have equal representation in the Upper House (Rajya Sabha), as in the US, where every state has equal representation in the senate. He also suggested that the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha should have equal voting power on Money Bills. He was afraid that, owing to the asymmetrical seat distribution in the Rajya Sabha, the north would override the interests of the southern states.

While debating in Parliament on the State Reorganisation Bill, he reiterated:

The question that requires to be dealt with in my judgement is a very serious question. Are we to have one State for one language, or are we to have one language for one State? If this question had no political consequences, nobody would bother about it, but the trouble is that this question has very serious political consequences. In the United States, the population of the various States differs. In some States it is small, and in some States it is big. But the Americans do not mind it on account of the fact that the States have equal powers. The Lower House has the same power as the Upper House, and all the States have equal representation in the Upper House without reference to population. In the Senate they have equal representation. Here, what is the position? Under our Constitution, there is no such equality at all. Every State has not the same power, and the Upper Chamber has no powers at all, so far as finance is concerned. It may happen – it is very likely – that the States in the northern area may combine together on an issue on which the southern States of India do not agree. What is likely to happen in that event? In that event, the north, if I may say so, will over-ride every proposition in which the southern States are interested. If that happens, I fear that there maybe civil war. I may be using some exaggerated sentiment, but such a thing has happened. It has happened in the United States.

Ambedkar also foresaw the consequences of the consolidation of the North at the expense of South India. Is it not true that the political parties of the Hindi heartland, particularly the ones with a national presence, often use this asymmetry to gain power in the centre? “These huge Hindi reptile provinces, which have been looming large before us. I shudder to see U. P. standing before me in that shape,” he noted. His solution was to create as many smaller states as possible out of these gigantic states.

He wrote:

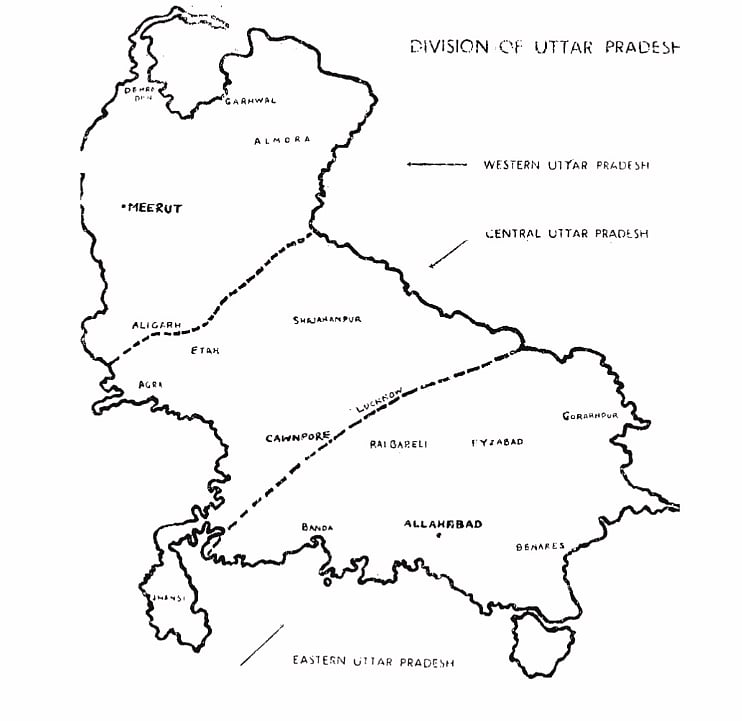

The problem having been realized we must now search for a solution. The solution lies obviously in adopting some standard for determining the size of a State. It is not easy to fix such a standard. If two crores of population be adopted as a standard measure most of the Southern States will become mixed States. The enlargement of the Southern States to meet the menace of the Northern States is therefore impossible. The only remedy is to break up the Northern States of UP, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.

He suggested that UP should be divided into three units, with Meerut, Kanpur, and Prayagraj as their respective capitals. Uttarakhand was carved out as late as 2000.

It is worth noting that in 2011, the then chief minister Mayawati passed a resolution in the UP assembly calling for the state to be divided into four parts: Harit Pradesh, Awadh Pradesh, Bundelkhand, and Purvanchal. However, the then Union government under the Congress-led UPA was not ready for it.

The proposals put forth by Mayawati were rooted in demographics. According to the 2011 Census, UP’s population was nearly 24 crore. There are only four nations in the world with a higher population than the state: India, China, the USA, and Indonesia. It consists of 75 districts, and it is almost impossible for a chief minister to visit all of them and receive regular updates on the development process. The Allahabad High Court is based in Prayagraj, and as it happens, the Lahore High Court is nearer to someone living in Saharanpur than the Allahabad High Court.

It has several developmental blind spots. The Bundelkhand region is one of India’s most deprived and deserted regions. It experiences a very high number of farmers’ deaths by suicide. In 2014, then-BJP Chief Minister Uma Bharti promised a separate state for the Bundelkhand region, but that vision never transitioned from rhetoric to reality.

Speaking of Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, Ambedkar advised dividing them into two states. This proposal was made decades ago, before the creation of Chhattisgarh from Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand from Bihar.

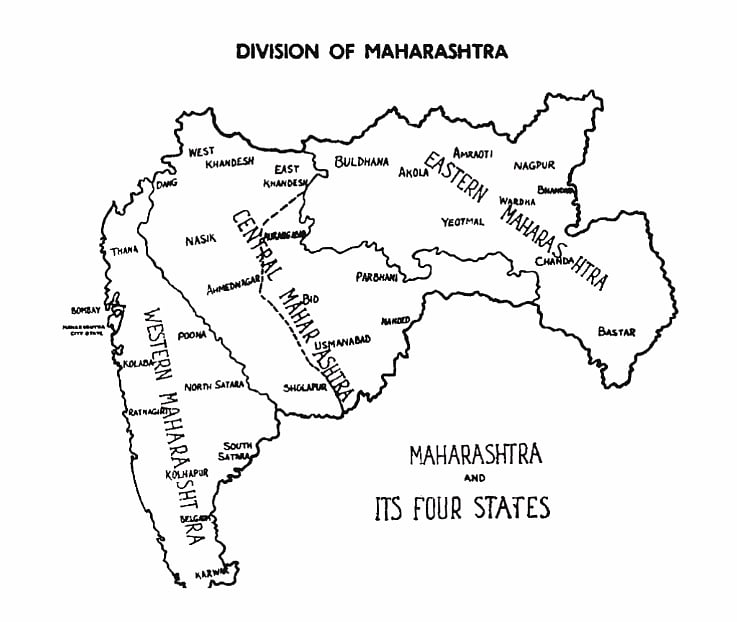

In Maharashtra, Ambedkar was especially worried about the state of Marathwada – a region that stood at the margins of social and institutional development – which received very little to no attention under the Nizam. It was in this context that Ambedkar, through the People’s Education Society, laid the foundation of Milind College in Aurangabad, creating pioneering institutional footholds for youth in the region.

Writing in his book, he said: I would divide Maharashtra into four States (See Map 5) : (1) Maharashtra City State (Bombay), (2) Western Maharashtra, (3) Central Maharashtra and (4) Eastern Maharashtra.

Backing this proposal, he gave many arguments.

My first argument is that a single Government cannot administer such a huge State as United Maharashtra. The total population of the Marathi-speaking area is 3,30,83,490. The total area occupied by the Marathi-speaking people is 1,74,514 sq. miles. It is a vast area and it is impossible to have efficient administration by a single State. Maharashtrians who talk about Samyukta Maharashtra have no conception of the vastness as to the area and population of their Maharashtra.

Further expressing his discomfort over economic, institutional and education inequalities in all parts of Maharashtra, with a special concern for the Marathwada region, he stated:

The second consideration is the economic inequality between the three parts of Maharashtra. Marathwada has been solely neglected by the Nizam. What guarantee is there that the other two Maharashtras will look after the interests of what I call the Central Maharashtra? The third consideration is industrial inequality between the three parts of Maharashtra. Western Maharashtra and Eastern Maharashtra are industrially well developed. What about Central Maharashtra? What guarantee is there of its industrial development? Will Western Maharashtra and Eastern Maharashtra take interest in the industrial development of Central Maharashtra? The fourth consideration is the inequality of education between Eastern and Western Maharashtra on the one hand and Central Maharashtra on the other. The inequality between them is marked. If Central Maharashtra goes under the Poona University its destiny is doomed.

One of his most critical remedies, which may sound radical to some, was having two capitals for India. He believed that the capital in Delhi not only alienates people living in the South but also creates inconvenience for them. He wanted a second capital from the point of view of defence as well. He called Delhi “vulnerable” and concluded that Hyderabad would be the best choice for the second capital.

He wrote:

Now we have a popular Government and the convenience of the people is an important factor. Delhi is most inconvenient to the people of the South. They suffer the most from cold as well as distance. Even the Northern people suffer in the summer months. They do not complain because they are nearer home and they are nearer the seat of power. Second is the feeling of the Southern people and the third is the consideration of Defence. The feeling of the Southern people is that the Capital of their Country is far away from them and that they are being ruled by the people of Northern India.

The third consideration is of course more important. It is that Delhi is a vulnerable place. It is within bombing distance of the neighbouring countries. Although India is trying to live in peace with its neighbours it cannot be assumed that India will not have to face war sometime or other and if war comes the Government of India will have to leave Delhi and find another place for its location. Which is the place to which the Government of India can migrate?

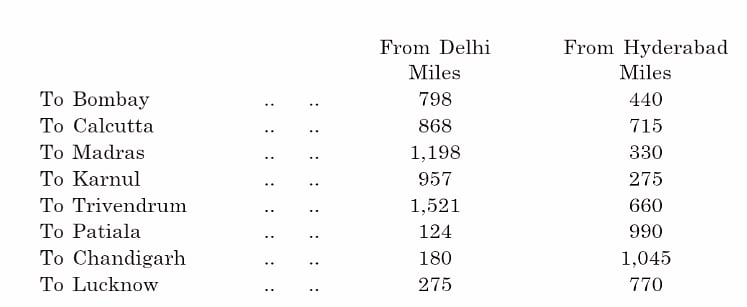

A place that one can think of is Calcutta. But Calcutta is also within bombing distance from Tibet. Although India and China today are friends, how long the friendship would last no one can definitely say. The possibility of conflict between India and China remains. In that event Calcutta would be useless. The next town that could be considered as a refuge for the Central Government is Bombay. But Bombay is a port and our Indian Navy is too poor to protect the Central Government if it came down to Bombay. Is there a fourth place one could think of ? I find Hyderabad to be such a place. Hyderabad. Secunderabad and Bolarum should be constituted into a Chief Commissioner’s Province and made a second capital of India. Hyderabad fulfils all the requirements of a capital for India. Hyderabad is equidistant to all States. Anyone who looks at the table of distances given below will realize it.

Ambedkar anticipated that gigantic linguistic states would result in the suppression of the interests of minorities. Explaining how this communal majority can become a permanent tyranny of the governing class, he wrote:

People who rely upon majority rule forget the fact that majorities are of two sorts: (1) Communal majority and (2) Political majority. A political majority is changeable in its class composition. A political majority grows. A communal majority is born. The admission to a political majority is open. The door to a communal majority is closed. The politics of a political majority are free to all to make and unmake. The politics of a communal majority are made by its own members born in it. How can a communal majority run away with the title deeds given to a political majority to rule? To give such title deeds to a communal majority is to establish a hereditary Government and make the way open to the tyranny of that majority. This tyranny of the communal majority is not an idle dream. It is an experience of many minorities. This experience to Maharashtrian Brahmins being every recent it is unnecessary to dilate upon it. What is the remedy? No doubt some safeguards against this communal tyranny are essential. The question is: What can they be? The first safeguard is not to have too large a State. The consequences of too large a State on the minority living within it are not understood by many. The larger the State the smaller the proportion of the minority to the majority. To give one illustration – If Mahavidarbha remained separate, the proportion of Hindus to Muslims would be four to one. In the United Maharashtra the proportion will be fourteen to one. The same would be the case of the Untouchables. A small stone of a consolidated majority placed on the chest of the minority may be borne. But the weight of a huge mountain it cannot bear. It will crush the minorities. Therefore creation of smaller States is a safeguard to the minorities. The second safeguard is some provision for representation in the Legislature. The old type of remedy provided in the Constitution were (1) certain number of reserved seats and (2) separate electorates. Both these safeguards have been given up in the new Constitution. The lambs are shorn of the wool. They are feeling the intensity of the cold. Some tempering of the wool is necessary. Separate electorates or reservation of seats must not be restored to. It would be enough to have plural member constituencies (of two or three) with cumulative voting in place of the system of single-member constituency embodied in the present Constitution. This will allay the fears which the minorities have about Linguistic States.

Under Article 1, the Constitution empowers Parliament to restructure any state in the interest of better governance. Ultimately, the modern state is designed to ensure the prosperity and security of its citizens; the state exists for the people, not the people for the state.

Today, India, with a population of over 130 crores, has only 28 states, whereas the United States, with around 33 crores people, has 50 states. Japan, with about 12 crore people, has 47 prefectures.

It is time to return to Ambedkar’s diagnosis and remedies, especially when his warnings are coming to haunt our republic. Delaying delimitation and continuing to freeze politics to the 1971 Census will not stabilise India’s federal structure. It is a tectonic fault line in our democracy, and it’s only a matter of time before the eruption.

Ritesh Jyoti is pursuing a Master’s in Development from Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. His research interests span Phule-Ambedkarite thought and Kanshiram’s politics.