From Watergate to watered-down: Every Indian journalist should read this piece

Bezos guts the newsroom, but the real story lies deeper – a business model that has traded investigative ‘watchdogs’ for lifestyle ‘content’ to appease an audience that refuses to pay for news.

The Washington Post – WaPo for short – has inspired journalists of several generations, thanks in part to Hollywood. Two Oscar-nominated movies have been made about the paper and its people. The first was All the President’s Men, based on the story of how the paper broke the mother of all investigations, the Watergate Scandal.

The second, Spielberg’s The Post, is a more intimate homage to WaPo, about how its owner, Katharine Graham, was ready to sacrifice the company’s IPO and even risk arrest to publish the Pentagon Papers.

There’s a pivotal point in the movie, when Graham – played by the always-excellent Meryl Streep – is warned by her board that institutional investors who backed WaPo’s IPO would abandon it if she went ahead with the story. Graham responds that investors “had already been put on notice,” that the paper stands for “outstanding news collection and reporting,” and is “dedicated to the principles of a free press.”

That Post is now dead. Its current owner, Jeff Bezos, buried it alive when he sacked one-third of the paper’s journalists this week.

But this is not just a story of a Big Bad Billionaire destroying journalism. It runs much deeper. It is a story about the fundamental changes in the way the business of news views the nature of news itself.

Now, to be fair to Bezos, most of the people laid off by WaPo came to the paper because of the money he poured into it. When Bezos bought WaPo from the Graham family in 2013, he was the 19th richest man in the world, and his fortunes were only looking up. But WaPo was haemorrhaging financially, losing more than $50 million annually.

WaPo had just hired a new Executive Editor, Martin ‘Marty’ Baron, a celebrity editor brought in from The Boston Globe (who would later feature as a central figure in the Oscar-winning 2015 movie, Spotlight). Baron immediately felt the pinch of not having money to spend on newsgathering. Bezos came in like a saviour of old school journalism, giving Baron a carte blanche to spend and make the paper great again.

During Baron’s reign, WaPo increased its newsroom strength from 580 journalists to over 1000. It opened offices across the world. Most importantly, Baron had the money to hire investigative journalists who were given the time and resources to pursue difficult stories. The result was that WaPo won 10 Pulitzers when Baron was the editor. Would this have been possible without Bezos? Unlikely.

Equally important was WaPo’s online thrust after Bezos took over. By 2015, it had become the most read newspaper online, pipping its more illustrious competitor, the New York Times, to the post. For the next few years, WaPo remained among the top 3 news sites, reaching a peak of 22.5 million daily active users (DAU) by early 2021.

On the face of it, WaPo was succeeding precisely because it had become bigger and better at old school journalism. But this had been made possible because of the underlying uncertainties and conflicts in America’s body politic. It was a time of great polarisation in US society, which ultimately led to Donald Trump's rise. And when Trump became President, WaPo consistently took an anti-establishment stance, becoming the voice of those dismayed by what was happening in Washington, DC.

WaPo’s run-ins with Trump during his first term cost Bezos heavily. Trump reportedly got the US Postal Service to double the rates it charged for delivering Amazon packages. Amazon Web Services lost a $10 billion Department of Defence contract for cloud services, and went to court accusing the Trump administration of personal animus against Amazon’s founder.

Then came COVID, which heightened fear, uncertainty, and doubt. Public interest in news reached an all-time high, pushing WaPo to its peak as well. More importantly, from Bezos’ standpoint, the paper turned the corner financially and began turning a profit, reversing years of losses.

What neither Bezos nor Baron anticipated was how quickly ‘news fatigue’ would set in among WaPo’s readers. Almost as soon as the lockdowns ended, people lost interest in pure news sites, and WaPo’s reach and revenues began to collapse.

Fortunately for Baron, it was already time for him to retire, and he left in 2021, before things fell apart.

Bezos wasn’t that lucky.

By the middle of 2024, WaPo’s daily active users had dropped to one-eighth of its 2021 peak. In terms of mindshare in political news (measured by Nate Silver’s Silver Bulletin), the paper had crashed by 64 percent from where it was during Trump’s first term. Worse still, from a business standpoint, WaPo was back in the red. Over 2022 and 2023, WaPo lost a total of $177 million.

So, Bezos brought in the controversial newsman Will Lewis to run the company.

Lewis, who had been named in the infamous News of the World phone-hacking controversy in 2011, started off on the wrong foot with people in the newsroom. His blunt, abrasive style antagonised senior journalists – many of whom had become minor celebrities in their own right. A New Yorker piece on the changes at the Post talked of Lewis and his team of “four white men,” speaking with “vitriol” about the newsroom and calling for journalists to be “disciplined.” It caused many of the Post’s most respected journalists to leave. Marty Baron spoke out from his retirement, calling the period “among the darkest days” in the paper’s history.

Lewis wasn’t the only one tasked with overhauling the editorial strategy at WaPo. The new philosophy at the top was to steer clear of politics. So, Team Bezos stopped an age-old WaPo tradition of endorsing a presidential candidate when it became clear the editorial team was planning to back Kamala Harris.

Then, in February 2025, Bezos directed that the opinion page would only publish pieces that promoted “personal liberties and free markets.” All other viewpoints were to be banned from WaPo’s pages.

Bezos was effectively saying, don’t attack Trump, don’t attack the rich, and don’t give any space to anyone who vaguely smells of socialism.

This was the most overt intervention in the paper’s editorial policies since Bezos had taken over and resulted in the resignation of the Opinion Editor, David Shipley.

If the censorship of the opinion pages and the decision not to endorse Kamala Harris were the more visible aspects of that change, deeper shifts were happening in what WaPo considered news. It now wanted to cater to people who were not interested in politics or ‘hard’ news, especially the TikTok generation.

So, Lewis came up with a ‘Three Newsrooms’ plan. The first was the ‘Core Newsroom’ dedicated to traditional journalism. The second was the ‘Opinion Newsroom’ to promote Bezos’ ideology of ‘personal liberties and free markets.’ And the third, perhaps the most important, was the ‘Third Newsroom’ – later rebranded as WP Ventures – which was to tap new audiences who do not care about the news.

The Third Newsroom was set up to reach people who were critical of traditional ‘mainstream’ news. It was to reorient itself to news as a service and lifestyle journalism. The newsroom was meant to provide utility to readers – wellness, financial tips, and also develop ‘personality-driven’ content. This was to be a ‘social first’ venture, generating reels and social media posts, and offering bite-sized subscription packages for those who wanted to graze rather than commit.

A crucial shift in strategy came in the middle of last year, when WP Ventures/Third Newsroom was moved from an editorial division and placed under WaPo’s Chief Strategy Officer, who was a non-editorial, corporate employee. The Third Newsroom’s managing editor, Krissah Thompson, who was the brains behind the venture, left WaPo, as did Dave Jorgensen, the ‘TikTok guy’ at the paper.

The next step was kind of obvious. If the focus shifted to non-news content, the newsroom was bound to be pruned, especially since AI platforms were already producing competent general news copy. After all, Bezos had also replaced people with AI agents at Amazon itself.

But the scale of the amputation has taken everyone by surprise – not just because of the sheer numbers, but because entire departments have been shuttered. Most prominent among them? WaPo’s much-respected sports team.

By trimming hard news content, directing opinion to only one kind, and pushing non-news, personality-led franchises, WaPo is trying to emulate what others have done in the world of online infotainment – most notably the New York Times. The NYT’s continued success has been driven by adding NYT Cooking and games to its portfolio, which brings in revenues from non-news readers.

NYT’s news content has also increasingly been slanted towards its core market – the affluent liberal who abhors excessive radicalism. This is clear from the paper’s one-sided coverage of Israel’s war in Gaza, and its ‘anti-endorsement’ of Zohran Mamdani.

Clearly Bezos feels that if the venerable Gray Lady can turn conservative on political issues, so can he and all his men at WaPo.

Is this the sign of things to come, across the world, where corporate owners of news organisations orient the philosophy of news gathering and dissemination towards their private vision of the world? This is nothing new for us in India, where the corporate control of news began more than a decade ago, and is only increasing day by day.

But it is disingenuous to blame the billionaires for this. They buy news organisations either to make money from them, or to increase their influence over society and the state. To expect anything else from them would be sociological naivety.

The real culpability lies with civil society – especially its affluent liberal sections – who have cut themselves off from hard news and consume it only in the form of a few words at a time, or as reels and shorts. We are willing to drop thousands on a meal, but won’t spend a fraction of it to support real journalism.

It would be good to remember the slogan WaPo’s last great editor, Marty Baron, had adopted for the paper’s masthead in 2017 – “Democracy dies in darkness.” We, the upper-middle class, who were once the opinion makers of civil society, are complicit in shrouding democracy in that darkness.

Editor’s note: You heard the man. Click here to subscribe.

What the ‘murder’ of Washington Post means for India

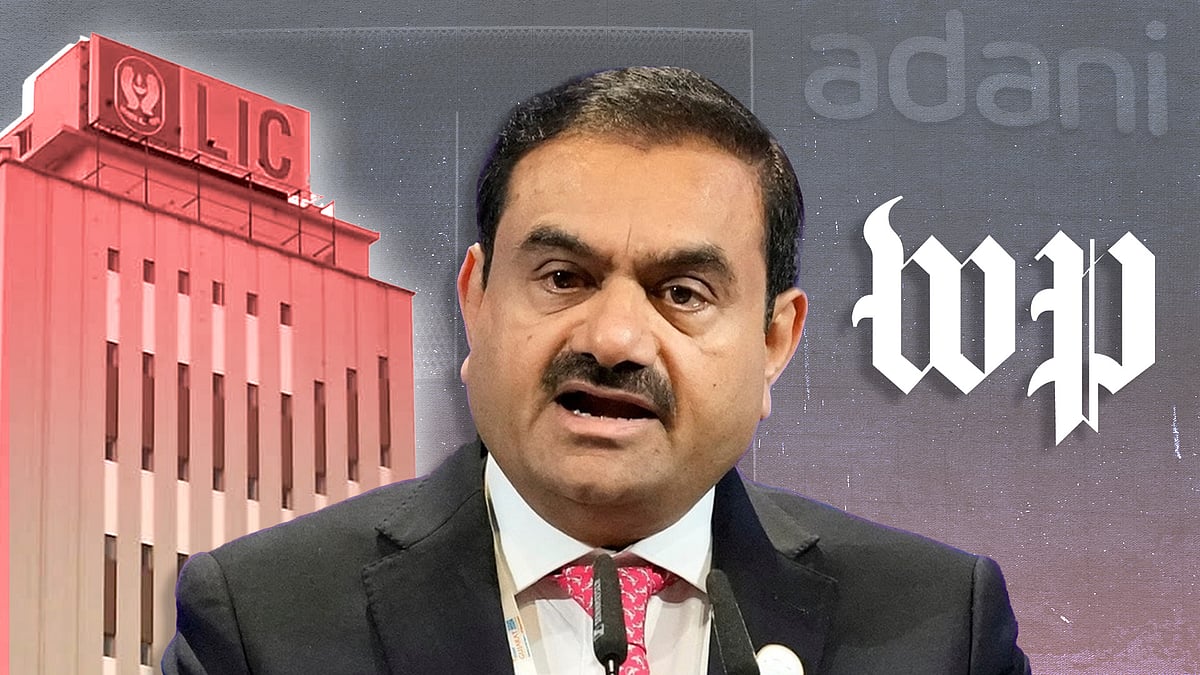

What the ‘murder’ of Washington Post means for India Washington Post’s Adani-LIC story fizzled out in India. That says a lot

Washington Post’s Adani-LIC story fizzled out in India. That says a lot