Epstein Files: Why the elite kept hitting ‘reply’ to a convicted paedophile

Knowledge of his crimes did not end relationships for the global elite; it merely changed how they were explained.

There’s a bunch of sick f***s. And the sickest part of all of this is that so many people knew.

US Representative Becca Balint from Vermont said this on February 9, after spending roughly thirty minutes reviewing unredacted Jeffrey Epstein files made available to members of the US Congress.

This was not a statement prepared for effect. It sounded more akin to a visceral reaction when someone encounters material that strips away the usual buffers people in public life develop with time, of legal language, institutional distance, and the comfort of speaking in abstraction – but this stuff strips away the fineries like a braided whip peels skin off the bone, recognition and the pure disgust of it.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way…this remains a developing story. Many US lawmakers have said that the volume of material already known to exist is so extensive that it could take years to examine properly, even before accounting for what may still surface. That uncertainty matters, yes, but it doesn’t erase what is already visible. There is enough material here to examine behaviour, not to pronounce final verdicts, but to understand how decisions were made once certain facts were no longer in doubt.

The question that follows is not about Epstein’s crimes. Those are established. But about what came after. About how power behaves when it encounters knowledge that should, in theory, impose limits.

How did association with a publicly identified sexual predator of underage women remain survivable in public life?

After the facts were known

Epstein’s criminal conduct was not something discovered only in hindsight. It was known, investigated, prosecuted, reported, and widely discussed while many of the relationships now under scrutiny were still active. This was not a case of moral clarity arriving too late; the clarity existed in real time, but the spine to act on it didn’t.

The first act of this cowardice, or apathy, if that floats your boat, was the suppressed testimony of Maria and her sister Annie Farmer in the infamous Vanity Fair article in 2003 by Vicky Ward. In 2015, Ward admitted in an article for The Daily Beast that the Farmer sisters’ testimony was indeed suppressed by the then-editor, Graydon Carter.

I wonder how many women would have lived happier lives, if Carter had shown some spine in front of a man accused of being a paedophile by two young girls… if only.

And yet, once that clarity entered the public domain, it didn’t serve as the stopping point one hoped it would. The social world around Epstein didn’t empty out. His meetings with the rich and the powerful continued. He continued to exchange atrociously written emails, and his invitations were still accepted. What should have acted as a disqualification instead became something to navigate, to sidestep.

This is where names matter; you should read that 2003 article for the name drop alone – not as a catalogue of guilt, but as evidence of how widely this accommodation extended.

The sitting US president, Donald Trump, and his relationship with Epstein are among the most well-known, not because they are the most intricate, but because of what they reveal about the systems that surround him. Trump is often treated as an aberration, a deviation from liberal democratic norms. But this skidmark of a human being’s ease within this ecosystem implies the opposite. Epstein moved comfortably through worlds that pride themselves on being enlightened, meritocratic, and governed by rules of fairness. Trump’s proximity to him didn’t place him outside that world; it placed him squarely within it.

That is the uncomfortable truth. The problem isn’t the existence of someone like Trump; men like him have always existed. But the problem is that the modern order, so often presented as his moral opposite, proved capable of absorbing the same compromises, rationalisations, and silences.

Financier Lex Wexner’s long association with Epstein was not marginal or fleeting. Academic Noam Chomsky’s correspondence shows an insistence on compartmentalisation, on treating Epstein as a logistical conduit rather than a moral problem, to whom Chomsky gave tips for manufacturing consent for PR. Filmmaker Woody Allen’s interactions sit within a wider context of allegations that were already part of his public record. Former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers’ relationship with Epstein endured long enough to require an apology years later.

Former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak was not merely present in Epstein’s orbit but also acted as a friend and facilitator, introducing each other to business ventures and political conversations. Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, CEO of DP World, the world's third-biggest ports firm, appears in unredacted congressional material discussing business and lurid personal matters with Epstein, to the point where a company in the Sultan’s name was used to purchase Epstein’s private island.

These are not chance encounters. They point to a world in which Epstein was treated as usable long after he should have been untouchable. Knowledge did not end relationships; it merely changed how they were explained.

The astonishing aspect of the documentary trail is not secrecy, but the ease with which everything related to Epstein is discussed; the emails are casual, and arrangements are unguarded. There is little sign of anxiety about being seen. To me, this reads less like concealment than confidence – confidence that even if these interactions become visible, they will not carry consequences severe enough to matter.

India and the quiet logic of usefulness

India’s presence in this story is less flamboyant, but no less instructive. Here, the issue is not spectacle but judgment exercised in plain view of available facts.

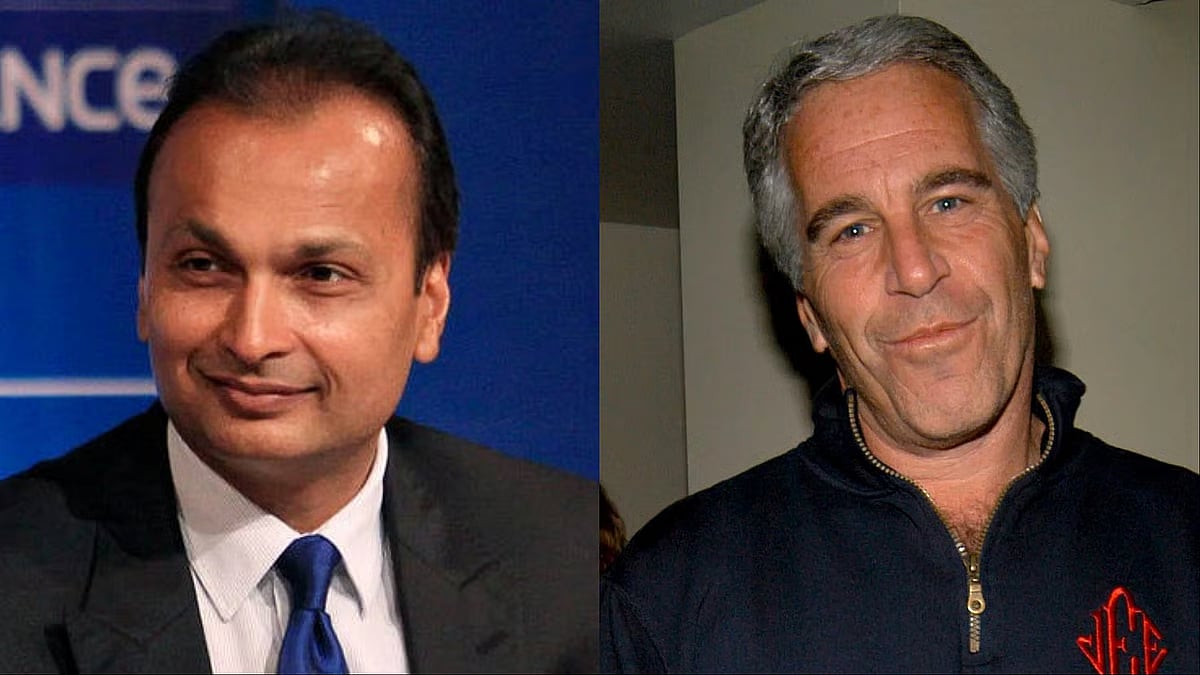

Anil Ambani appears in documents as a bridge between Indian political "leadership" and figures such as Jared Kushner and Steve Bannon, with Epstein functioning as an intermediary. This suggests not incidental contact but instrumental proximity. The obvious question follows: why was someone with Epstein’s public record considered acceptable as a connector at all?

The case of Hardeep Singh Puri brings this into sharper focus. Emails from 2014 show him discussing India’s investment landscape with Epstein and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman. Beyond correspondence, Puri reportedly facilitated priority visa assistance for Epstein’s assistant to travel to India for a wedding, extending diplomatic contacts for a plainly private purpose.

Then there is the smaller, revealing detail: Puri seeking an appointment to personally present his book to Epstein at his New York home. I understand writers want readers; that impulse is human. But why this reader? Epstein was not known as a serious intellectual interlocutor. His documented role in elite life was as a fixer, a facilitator, a broker of access. His correspondence bears that out.

This detail matters because it moves the question beyond obligation. It points toward perceived advantage. Toward a willingness to cultivate proximity where no clear public purpose existed.

More than brazenness, it’s the matter-of-fact normality which is most striking. There is little evidence that these actions were seen as requiring special justification at the time. The assumption appears to have been that if questions ever arose, explanations would suffice.

This is how trust erodes – not through any single dramatic rupture, but through the steady widening of what is treated as acceptable.

Who does the system move fast for

To truly understand this story, pay attention to timing. Not when abuse occurred, but when urgency appeared.

One of the most disturbing aspects of this story is the asymmetry of urgency. When victims sought help, they encountered disbelief, procedural delay, and institutional exhaustion for years. Their accounts moved slowly through institutions that seemed perpetually cautious when the implications involved powerful people. Time worked against them because while the evidence and testimonies age, their trauma compounded. Lives were shaped by what they carried forward largely on their own.

Contrast this with the moment reputational risk became acute, like today. Legal teams and crisis advisors were engaged, and teams were assembled at breakneck speed to draft the statements. Suddenly, the collective memory became selective, and distances were asserted. The machinery of protection sprang up with remarkable speed and coordination.

To believe this contrast is accidental is burying our proverbial heads in the sand. It tells us precisely whose interests these institutions were built to serve.

In Australia, former prime minister Kevin Rudd appears in documents as part of Epstein’s social circle, even as his office later denied attending specific gatherings. Katherine Keating, daughter of former PM Paul Keating, appears as a social intermediary. In Europe, figures such as Peter Mandelson and Thorbjørn Jagland surface in contexts involving access, private meetings, and information that sit uneasily alongside their public responsibilities.

In Norway, Crown Princess Mette-Marit’s name recurs in Epstein-related correspondence, which, for some weird reason, involves questionable decor for her son. Who in their right mind thought Epstein was the guy I should consult about how to act with my own child?

In Africa, emails reference former South African president Jacob Zuma, while other material points to Epstein’s claimed involvement with financial arrangements linked to the Mugabe family.

Not every mention implies the same thing, and not every interaction carries equal weight. But taken together, they show how widely Epstein was treated as someone who must be accommodated, explained, and managed rather than excluded.

The most recent material only sharpens this picture. Hind Al-Owais, a UAE diplomat whose professional work has centred on gender equality and human rights, appears in newly surfaced correspondence that displays a level of familiarity difficult to reconcile with those roles. Messages discussing “getting girls ready,” including references to her younger sister, do not merely contradict stated values; they expose how easily language of protection and empowerment can coexist with private conduct that empties those words of meaning.

The Epstein material reminds us how fragile that assumption is when private behaviour remains insulated from consequence.

What knowing was worth

Over the years, every time a new, fresh hell surfaces, in this case sprawling continents through decades, an Einstein quote pops into my head: A question that drives me hazy: am I or the world crazy?

With time, the Epstein archive will become more legible. Documents will be ordered, claims weighed, false leads discarded, and timelines corrected. Historians will do what they always do: distil the chaos into sequence. I feel that's the easy part. What will be harder to explain years from now is not what happened, but how little resistance it encountered once it was known.

Complaining about the media is easy. Why not do something to make it better? Support independent media and subscribe to Newslaundry today.

Convicted sex offender Epstein’s files show Anil Ambani was in touch over deals and govt issues

Convicted sex offender Epstein’s files show Anil Ambani was in touch over deals and govt issues Longtime media ally Murdoch is Trump’s latest target after Epstein report

Longtime media ally Murdoch is Trump’s latest target after Epstein report