Caste in stone?

On the 125th birth anniversary of Dr BR Ambedkar, it is worth asking if casteism is even close to being a thing of the past.

Years ago, when the school master in his hometown admonished him by hollering, “Naapiter chele naapit e thakbi. Tor kichchhu hobena!” (“A barber’s son will remain a barber. You will amount to nothing!”), it was just a routine dressing-down at school for young Prosenjit Sheel.

Sheel, now in his 20s, grew up in a small town named Dalkhola in Uttar Dinajpur district, West Bengal, in the early 1990s. “It did not feel like a casteist insult back then,” he said. “Perhaps I was too young to comprehend. But now, I feel that a young boy should not have to hear such slurs in an educational institution.” From those early days in Dalkhola to becoming the first graduate in his family and earning a Master’s degree in Ecology, Environment and Sustainable Development from TISS, Guwahati, it has been a long journey for Sheel.

The Scheduled Caste (SC) certificate he’s carried has been an enabler, opening doors that would have been firmly locked otherwise. “My father had to shell out Rs 7000 to get this piece of document, despite being a rightful claimant to it,” said Sheel. “This was at a time when he used to earn Rs 80 a day. Such was the lack of awareness in the family that he did not even realise that the document was our right, and not something we had to pay for.”

Despite how it helped him, Sheel says he would no longer use the certificate to avail benefits of reservation, now that his education is complete. “Nor will I encourage my subsequent generations to avail the benefits of the quota system,” he said. “I am educated and empowered now, and I know how to fight for my rights.”

The stance adopted by Sheel would perhaps be applauded by the likes of Rajesh Chaubey, a 20-something IT professional from the National Capital Region. Chaubey, who frequently shares posts on his Facebook about the “woes” of the general category students, feels caste is politicised in this country just for the sake of ‘vote-bank politics’.

“Caste-based reservations are being used against the general caste,” he said. “It is not necessary that those from the general category will all be rich, and SC/STs will all be poor. If anything, reservations should be given on the basis of economic prosperity.”

This is a popular view among many, but it betrays a lack of understanding of the basic concept of the reservation as a tool for social justice and not poverty eradication. The narrative of victimhood among dominant castes that Chaubey talks about has, in the past, given rise to agitations by Jats in Haryana, Patidars in Gujarat, Rajputs in Uttar Pradesh and Marathas in Maharashtra seeking OBC status. Though some have called the protests “absurd”, the common thread in all of them is that of caste-based reservations being looked upon as a welfare measure to be availed. Rarely is reservation seen as a means of redressal for discrimination related to caste.

Back to the future?

“Social stigma takes a long time to go because these are cultural changes. Cultural changes take longer than economic changes to happen,” explained Professor Badri Narayan Tewari, who teaches Social History at GB Pant Social Science Institute, in Allahabad. A quick look at the history of caste-based reservation in India proves Professor Tiwari’s point. There are Dalit businessmen, doctors, lawyers and every other profession that you can think of, however, the prejudice remains and consequently, so does the need for reservation.

The idea of offering preferential treatment to redress the balance in favour of the socially disadvantaged has been around in India since as far back as the 1800s. In regions like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the colonial government had introduced quotas when faced with pressure from ‘backward’ castes, who protested against the stranglehold that Brahmins had upon jobs and scholarship. In the early 1900s, Shahuji Maharaj of the princely state of Kolhapur became the first Indian royal to introduce reservation in education.

During the Round Table Conferences, which were organised by the colonial British government to decide what kind of systems would be put in place for a democratic India, Dr BR Ambedkar had argued in favour of reservation and said that that Dalits should be regarded as a minority community. While the British were convinced by his arguments, Gandhi opposed Ambedkar. Ultimately, the two reached an agreement of sorts with the Poona Pact of 1932. Gandhi grudgingly accepted Ambedkar’s demand of Dalit constituencies. Ambedkar had suggested a review after 10 years to see if political reservation was still necessary. This is often held as an argument against quotas for educational admissions and jobs, even though Ambedkar had been speaking about electoral politics.

Whether or not Ambedkar genuinely thought caste biases could be eradicated in a decade or not, there’s no doubt that he and his generation were genuinely hopeful that social change would move at a faster pace in independent India. The Constitution of India actually declares the caste system abolished and untouchability is considered a criminal offence. Yet, more than 60 years later, the numbers suggest that Ambedkar and the Constitution may have been a little more optimistic than the reality of India warrants.

Caste discrimination in modern India

A 2014 survey conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) and the University of Maryland in 42,000+ households across India showed that 27% respondents admitted to practising untouchability in some form. What is alarming is that 20% of urban households said that they practised untouchability.

Even among those who believe themselves to be progressive and liberal, there are subtle forms of casteism that continue to be in play. Often, they are often cloaked in the name of hygiene, said Kavita Krishnan, Secretary, All India Progressive Women’s Association and Polit Bureau member, CPI(ML). “Sanitation workers or even domestic workers in modern day households are not allowed to use the washrooms inside the employer’s house, because the notion is that their using the washroom will somehow make it unclean. It is another matter that these very people are employed to clean your child’s shit,” she said.

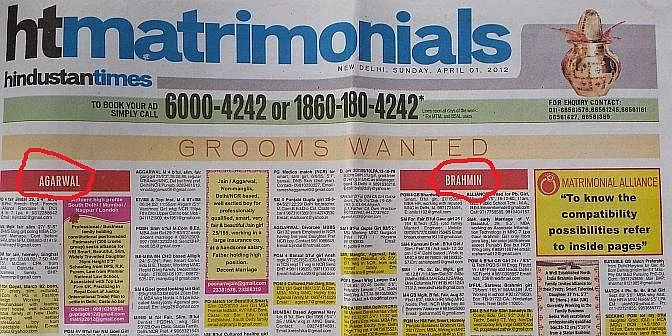

The same survey showed that just 5% of Indian marriages are inter-caste in nature, which indicates that the breaking of age-old taboos has barely begun. It’s not just The Hindustan Times that carries the categories shown in the image below. It’s standard practice among most matrimonial listings. “In marriages, people still look for partners within the same caste. Out of caste love marriage is looked upon as an embarrassment. Casteism is a naked truth and it has to be admitted,” said SP Singh Baghel, President, OBC Morcha, Bharatiya Janata Party

“You’ll find Hindu-Muslim marriages, you’ll find Muslim-Christian marriages, but Brahmin-Dalit marriage? Not likely,” said Swapna Mandal, a retired bureaucrat from Bengal. “The way caste persists is obvious in so many ways, like Christian ‘Brahmins’ not marrying Christian ‘non-Brahmins’. Even though they’ve converted generations ago, a lot of Christians hold on or claim a caste identity.”

Caste-based housing societies, casteism in university campuses are just a few indicators that casteism continues to thrive in urban settings, despite higher levels of education and greater exposure. It is safe to say that the dream of a casteless society, as envisioned by Ambedkar, is far from being a reality. On one hand, we have a young, aspirational India, with our fastest growing economy. Arguably, this is one of the best times to be born in India. Yet, despite all the steps forward, tragedies like what happened to Rohith Vemula show casteism is much more than a vestige of our past. It is so deep-rooted in our collective sensibilities that we have not been able to shake it off, even after all the efforts that have been made by generations of social reformers.

While people like Sheel may like to think that the shackles of caste do not bind him anymore, it is worth asking if society won’t discriminate against him anymore on the basis of his caste and see him differently because he has an education and a job. Can reservation really can change the way we think about caste?

There are no easy answers.