Rakhigarhi: When sensationalism trumps science

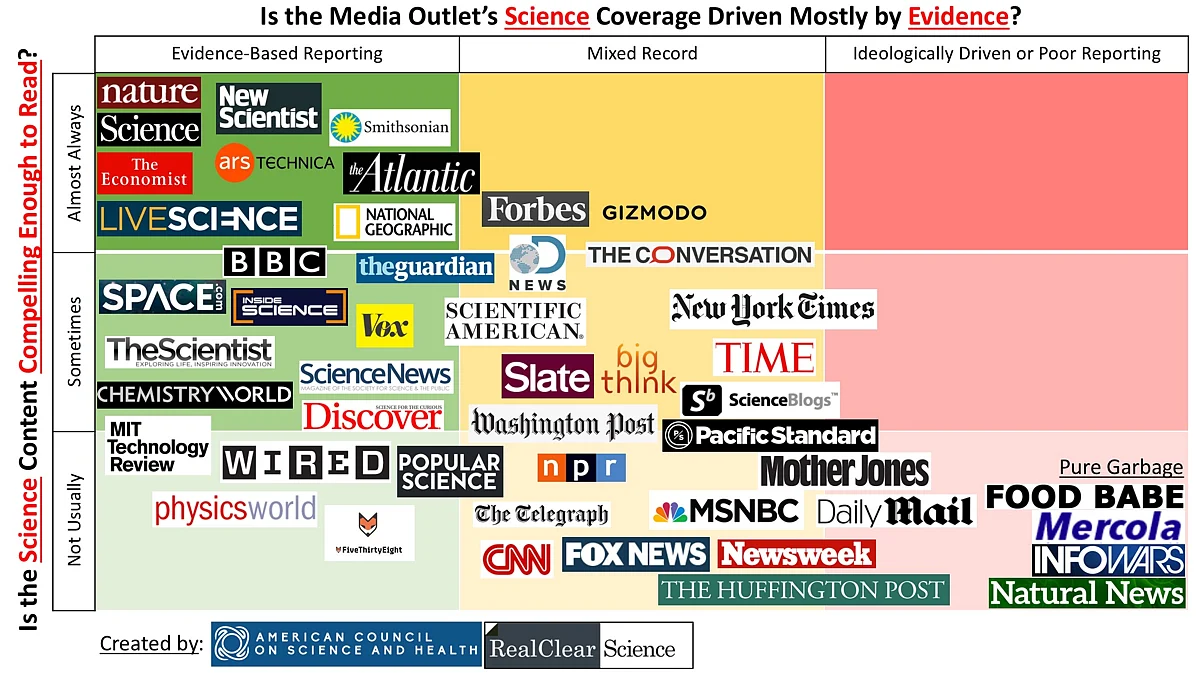

A critique of science reporting in mainstream media.

Recently, we received a “what do you think?” email regarding a story published in India Today. The title “4500-year-old DNA from Rakhigarhi reveals evidence that will unsettle Hindutva nationalists” immediately attracted our attention. The article goes on to elaborate on a study in which scientists examined the genetic composition of a 4500-year-old skeleton, unearthed at the Indus valley civilization site of Rakhigarhi, in Haryana.

The conclusion of the India Today report was that individuals of the Harappan civilisation shared genetic features with present-day tribes of Southern India, but not with the present-day local population of Haryana. This (according to them) suggested that the later Vedic Period involved the second wave of migration (Aryan migration theory), which gave rise to (and contributed to the genetic markers which are seen in) the present-day North Indian population. This report, in turn, fueled further pieces in Scroll and Swarajya magazines. Our take after reading the whole story: nothing. As no credible evidence was presented we have no take but plenty to say about the gaps in covering the scientific research.

Toil – Write – Review – Publish.

Before we unpack our reactions to the story, let us introduce you to the world of scientific publication. In pop culture’s shallow portrayals, scientists have Eureka! moments with alarming regularity, quickly followed by a Nobel prize and universal glory. In reality, though, science is a tediously slow process and rightly so. The Eureka! moment follows and is followed by years, sometimes decades, of painstaking efforts in one’s field of study. Marie Curie proposed the existence of ‘Radium’ in 1898, but she had to work 12 more years to isolate the radioactive element! One of us, during a summer internship, became aware of how crystallization of a particular snake venom protein (to study its structure) took 12 years of sustained effort. In science, it is not good enough to merely state- hypotheses have to be tested through experiments. These experiments to flesh out evidence must be accompanied by well thought out controls before results can be published in a scientific journal. Gathering data is just one half of this story. The second half is communicating it, as a scientific paper, to our community in particular and the world at large.

The scientific evidence and conclusions when submitted to a scientific journal, are put through the wringer of Peer Review. This involves the paper being sent to at least 2 scientists (not involved in the study) who have some authority on the subject. They scrutinize the data presented and conclusions drawn, and submit their critique of the paper to the journal. This can involve one of the following:- rejecting the paper altogether when the data does not support the claims, asking the scientists to perform more experiments to improve the data, to tone-down their conclusions in light of the data or, in rare circumstances, accept it as is. Essentially, one must remember, a paper in its final approved version may be notably different from its submitted version.

Although imperfect (and the subject of much criticism), the process of peer review helps scientists to adhere to basic standards of data quality and ethics when presenting and discussing their findings. It is the set standard in science and our community relies on it.

The online repositories.

In recent years, mostly due to delays in peer review and final journal publication, non-journal online alternatives have come forth for quicker dissemination of scientific findings. Physicist Paul Ginsparg developed arXiv in the 1990’s, an e-print repository for papers in physics and mathematics, whereas in recent years Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory (CSHL) started hosting a repository called bioRxiv (pronounced bio archive) for biological sciences. Scientists can directly upload their research work (papers) here, allowing quick access to the data for the rest of their scientific peers. As is evident, these articles are pre-print and not peer-reviewed but invite open critique through a comment section where fellow scientists can point out discrepancies or discuss findings. Typically, after community inputs, the work is revised and then sent to a journal. Thus, pre-prints act as a buffer for rapid communication with scientific colleagues. The authors benefit from community feedback before they submit their papers for formal peer review.

The intent of a scientific paper.

The intent of a scientific paper is to state bare scientific facts as they are.

In their papers, scientists are careful to keep their conclusions objective and as close to supporting data as possible. And if they do speculate on the greater impact of their findings they make sure that the language indicates that clearly – without sounding definitive. Indeed as a matter of norm, in a discussion section, researchers highlight the strengths and weaknesses of their work in light of other concurrent research taking place. This is vital to the spirit of scientific discussion.

The empirical, objective language used in scientific papers arises out of the necessity to stick to the facts (amongst other factors), but it also makes them dry, jargon-laden and boring for a general audience. It is here that the role of the science communicator or journalist is vital as he/she must convey the value of the research to a larger general audience while retaining the essence of the study. Results and conclusions do have caveats, and for the reader who as the taxpayer is science’s primary investor, this nuance should be made crystal clear.

This long preamble is necessary to understand our frustration with Rakhigarhi coverage in the media. To be clear, we are not discussing the merits or demerits of the study itself.

The hocus-pocus coverage of the Rakhigarhi study.

The India Today story that got the ball rolling, suggests the study being discussed is neither accepted nor published in a scientific journal (“the paper suggesting there is likely to be online in September and later published in the Journal Science”). This means that the data was not yet public (and is still not at the time of writing this article). So there is no way by which other scientists or the general public can look at the results and ascertain and understand the conclusions of the paper (if they are indeed the same as the India Today report). Though media does cover stories on yet to be published science*, such reports should be presented in a larger context with adequate background and full disclosure regarding the status of research. Background information can either involve interviewing other scientists in the field who have seen the work but are not involved in the study and/or quoting previous studies in the field.

The India Today article quotes two authors from the yet-to-be-published Rakhigarhi paper, geneticist Niraj Rai who appears to take a cautious approach towards interpreting the data by pointing out the drawbacks of the study (“We do not have much coverage of Y chromosome regions of the genome”) and archaeologist Vasant Shinde who has a completely contradictory conclusion to the one drawn by the India Today article (“Shinde…..dropping broad hints that the Rakhigarhi results would point to a continuity between population of the ancient town and its present-day inhabitants”).

The headline-grabbing conclusion reached by India Today is surprising given that neither of the two authors involved in the study categorically says so, nor is the data made available for others to draw such conclusions. To its credit, it does state that “certainly any triumphalism or despair on the basis of the emerging scientific profile of the Harappan Indians would be misplaced”, but this is buried deep within the article.

Why have a title that is so misleading, and the main point buried so deep?

This was followed by a piece in Swarajya which calls the India Today article a propaganda piece and then goes on to examine the “non-evidence” presented in the earlier article. The article says “I am not sure if the authors of the soon-to-be-published paper, Prof Vasant Shinde and Dr Neeraj Rai, among others, have made the unqualified, sweeping claim that the Harappans were closer to present-day South Indians than North Indians, based on the genetic analysis of DNA from a few skeletons, as the author of the India Today article, Kai Friese, has done”. We are not sure if Swarajya tried to contact the authors of the Rakhigarhi study or they did but got no reply. The article does not say anything about this. The irony of two “news” sites sticking to their beliefs and debating science without evidence would have been funny if it weren’t so tragic. Then we have Scroll publishing a long-form article supporting India Today’s conclusion. What do they base their conclusions on? At this point for sheer self-preservation, lest our brain circuits malfunction, we stopped trying to make sense of these articles – once again…….where is the data!!

So what must a reader expect?

Here are some things a reader should look for in a good (especially long-form) science reportage:

First, context. A brief primer to the area of research familiarising reader with the field at large.

Second, a clear indication of the publication status of scientific work being covered. Is it yet to be submitted, under review or approved for publication? A link to the pre-print or published form of the scientific paper should be included, if available.

Third, results and significance. It explains why the particular research being reported on is interesting and/or important. Importantly, it includes interviews with scientists directly involved in the study and with other scientists from the field. This allows the reader to match the claims of the journalist with the claims of the scientists.

Fourth, counterpoint. It includes interviews with scientists who may not agree with the methodology or conclusions of the study or studies with completely opposite or different conclusions thereby highlighting possible weaknesses of the study.

Fifth, in the spirit of full disclosure, states the funding source.

Due diligence by science reporters can help in educating people not only about the latest in science but also about the process of science, scientific method and rational thought. Baiting people by stoking embers of controversy in the name of science is not just harmful, but dangerous to the cause of facts and truth. Even the best in journalism can’t help sensationalising when covering science. But even if you have to sensationalize science, do so with facts.

The more concerning aspect raised by the India Today article is the impact of politics and political ideology on Indian scientific research. A deep dive into this issue (instead of getting into the whole Hindutva/ Aryan migration debate based upon an unpublished article) would have been more useful. India Today report claims that the Rakhigarhi paper publication has been delayed due to fear of political environment and the Hindutva agenda. It also quotes a Reuters report on a History Committee meeting convened by Union Minister of Culture, Mahesh Sharma “to present a report that will help the government rewrite certain aspects of ancient history”. This environment, if true, is dangerous for science. Science gives us facts, which may or may not agree with our beliefs, we all (including scientists) have to learn to deal with it.

*One of us, DS, feels if the study/paper has not gone through peer-review it must not be reported on.

Thanks to Ajit Ray for inputs and for reviewing the piece.

Divya Swaminathan is computational biophysicist affiliated with the University of California, Irvine and Swetha Godavarthi is Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Neuroscience in UCSD