Manu Joseph’s weekly baiting of the ‘asparagus-eaters’ is getting boring

His once uncomfortable truths are now almost completely replaced by cringe-inducing equivalences.

“Sanders or AOC might see in the riots what they wish to see—a majority oppressing a minority. ‘Hindus and Muslims equally to blame’ is not a story, not even a retweetable tweet.”

That’s what Manu Joseph wrote in his latest column for Livemint. The purpose of this piece — the latest addition to what is now the Manu Joseph genre — is demonstrating that victims aren’t really victims and oppressors aren’t really oppressors.

Manu Joseph has long fashioned himself as an unsentimental teller of uncomfortable truths, a provocative slayer of prevailing narratives. As the years have rolled by, however, uncomfortable truths have been almost completely replaced by cringe-inducing equivalences. His provocations have mutated from means to ends in themselves.

As in all other articles of this genre, a combination of dubious claims and false equivalences are carefully marshalled to sell this “hard truth”.

“From reports that have emerged, it is clear that in the first hours both Hindus and Muslims were responsible for the violence. But then, cops sought revenge on Muslims for a violent attack on them.”

Unlike airy academics who deal with concepts such as state complicity, Joseph, our sober purveyor of complex reality, concluded that the Delhi police merely retaliated against Muslims — over several days — due to “a violent attack” on them. Ashutosh Varshney, who has worked on riots for three decades, called the violence a pogrom. But Joseph deduced from a grand total of two videos that it was just a riot for which Hindus and Muslims were equally responsible, with the police apparently taking sides out of anger.

That’s not all. The Bharatiya Janata Party, we are led to believe, is unable to convey this “dull fact” of the riot because the powerful tell bad stories of their suffering.

Though there were victims on both sides, the brunt of the riots was borne by Muslims. There have been at least 16 mosques destroyed, but not one temple. The names of the deceased in this report indicate that more than 30 of the victims are Muslim and around 18 are Hindus. Surveiling the destruction of property, a New York Times report noted: “Though property belonging to Hindus was burned, the destruction was much heavier on the Muslim side. In Muslim areas, shop after shop was destroyed and entire markets were burned down.”

However, the reason it has been termed a pogrom is not because of the predominance of Muslim victims but because of state complicity in the violence, where the police either stood back or actively aided the mob in their attacks on Muslims. Even the police investigations and arrests have disproportionately targeted Muslims.

On what caused the riots, Joseph employed even more ridiculous equivalences in his previous article: “Politicians and activists then said things that provoked Hindus and Muslims alike. We don’t know who cast the first stone; we never know because we have naive definitions of a stone and casting.”

No citation is provided of who these mysterious activists might be but it must no doubt be true because in the Joseph world, every story must necessarily have two equally bad sides. Also, activists are behind everything bad that ever happens. He made sure to blame “disruptive and illegal street agitations” in the same sentence where he blamed a politician who “overtly threaten[ed] agitators”.

The article is titled “Riots happen because we romanticize chaos” — because riots happen not because of the “institutional system of riot production” (Paul Brass) or electoral incentives (Steven Wilkinson), but because Indians are “innate villagers”. The well-documented empirical reality of actual villagers hardly ever indulging in communal riots (until fairly recently) doesn’t really concern Joseph. Like the people he claims to oppose, he never lets facts get in the way of a good story.

But he insists his preferred stories are “dull facts” while other people’s even well-evidenced claims are stories jaundiced by empathy.

Joseph seems to have become trapped in his own persona. In his single-minded pursuit of being edgy and provocative, he’s come to resemble the most “un-edgy” of creatures: a middle-class Indian uncle. You know the type of uncle who constantly rails against intellectuals, activists, liberals, leftists, higher education, environmentalists, feminists, etc — and does so with the moral certainty and casual dismissiveness only found among middle-class uncles.

Rather than a thoughtful sceptic of prevailing morality in the Nietzschean mould, Joseph comes across more like an annoying undergrad 50 pages into Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. Sample Joseph’s declaration in an essay titled “The golden age of victimhood”: “The age of the strong and silent has passed. These times belong to the fragile loud.”

Even domestic violence has two sides in Joseph’s world. When Aishwarya Rai complained about being harassed by Salman Khan, Joseph noted that even though “Aishwarya Rai has almost gotten away with the much sought after title in the New Age: 'victim'”, she couldn’t have been one because “she is a lot smarter than that”.

While the story of “a pretty girl, brutalised by a shirtless man, forced to scream in public” might make for a compelling story, Joseph wants us to consider the role of Rai in her own victimisation.

“It's believed that it was Aishwarya who strongly influenced Vivek to hold that headline-hogging press conference a few days ago,” Joseph furnished as “she had it coming” evidence, while breezily mocking her for presenting the “trauma” of her “sensational ankle fracture” as a “near fatal accident”.

Victimhood is a recurring trope in Joseph’s writing, which he usually shrugs off as either exaggerated or manufactured or the artifice of activists. There is valid critique of activists in his older writings, but that has now long been buried below the reactionary reams painting all activism as selfish, foolish and harmful.

The problem is not just that Joseph’s broadsides against activism reflect a poor understanding of democracy, where urban middle-class activists play a key role in spreading awareness and organising people in a poor country, and where arguing against activism is essentially advocating a state that can take away land and resources from people at will.

The more troubling problem is that in so thoroughly lining up against activists, and in turn rejecting “causes”, Joseph finally ends up dismissing the suffering of the marginalised.

Here’s what he wrote in a piece in 2016: “Farmer suicide is a depression story, not an economics story. Tibetan monks who immolate themselves in protest against China are a depression story, not a political story. Suicide bombers are a depression story, not a radical-Islam story. Rohith Vemula, from all evidence in plain sight, is a depression story, not a Dalit story.”

Joseph is probably not a bigot. Nor is he dumb. On the contrary, he’s an exceptionally bright and gifted writer, armed with a perceptive eye and a sharp wit. His terrible opinions stem not from any intellectual frailties but from an all-enveloping narcissism.

Like Tavleen Singh (and her son Aatish Taseer for a while), his dispute is essentially with some of his former friends and acquaintances in his metropolitan intellectual circles. He constantly strives to show them up as out of touch and conceited and, in turn, validate himself as a rare brave and honest intellectual. In seeking to triumph in this intra-elite intellectual argument, he does not care which marginalised community he tramples upon, or which poisonous force he rationalises.

In an essay that might well have been autobiographical, he claimed: “Many ordinary people who appear to be ‘right-wing’ are so because they hate that one leftist, maybe two.”

The following passage is worth quoting in full to get into the mind of Manu Joseph:

“You love the world, but hate the self-righteous. You cannot be on the same side as such people. You want to build an argument against them. You don’t want to have the same sham views as these people. You despise those who inherited their wealth and write long essays lamenting inequality; you are tired of slighted academics getting back at the government through righteous attacks on its policies; and of the clinically depressed who see a world as bleak as their own lives. You can see what these people believe — that they are somehow morally superior to you because they feel beautiful feelings.”

In reflexively taking positions opposed to that of academics and intellectuals, his arguments have become not just bizarre but downright atrocious. In one essay, Joseph set himself to argue that the caste system has the inadvertent benefit of giving the poor “a monopoly over some professions”, citing the lack of competition Dalits face in skinning dead cattle.

“Some intellectuals claim that Dalits are ‘entrapped’ by such professions,” Joseph wrote, but the “Dalits themselves do not see their circumstances this way”.

It is hard to decipher where Joseph arrived at this insight, though it probably wasn’t from Dalit literature which he dismissed as “lament literature” in another piece titled “If Dalits bore you are you a bad person?” (The short answer, per Joseph, is no, since indifference towards Dalits is understandable, it’s compassion towards Dalits that is actually dangerous.)

Not content with merely erasing the oppression of Dalits, Joseph went further to claim that it’s the Brahmins that are, in fact, more oppressed by caste-based occupations: “The fact is that the castes that intellectuals hail from dictate their professions in a more inescapable way. Isn’t a Brahmin, after all, fated to be in software, surgery, finance and academics? The elite of India is entrapped in a sophisticated version of cow-skinning.”

The worst thing that can perhaps be said of Joseph’s writing is that it has become predictable to the extent of being boring. His insights nowadays mainly comprise repurposed clichés about liberals and activists that can be found in less elegant prose in internet comment sections. His arguments are restricted to blurring the nature of any given injustice using similarly tired equivalences.

In brief, Manu Joseph has transformed himself from a sharp thinker and writer into a glorified troll, whose sole purpose seems to consist of baiting the “asparagus-eating” crowd every week.

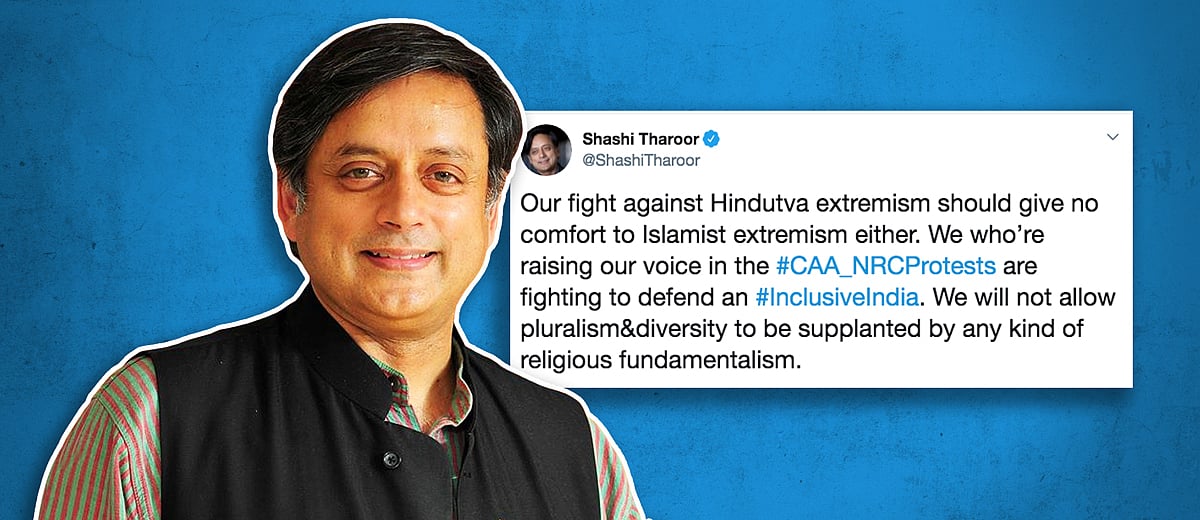

Shashi Tharoor and the majoritarian strain that afflicts Indian liberalism

Shashi Tharoor and the majoritarian strain that afflicts Indian liberalism