Why the majority’s concerns must be heard as much as a minority’s in a pluralist society

In the press coverage of communal violence, for example, the pain and anxieties of victims from the majority community cannot be ignored.

Sir Roger Scruton, one of the most important British philosophers of recent times, died early this year. While there’s a lot he can be remembered for, his insight into equal treatment of groups in a pluralist democracy is of particular relevance to understanding some of the churnings of our times.

Scruton was alive to a key issue confronting a pluralist democracy: all groups, big and small, should get equal treatment and respect in a pluralist society. However, in exclusively pursuing the interests of a small or minority group – social, linguistic, religious – is the equality principle being subverted to ignore the concerns, fears and interests of the majority? In a particular stream of liberal political thinking, which of late has even abandoned the individual to prioritise group identities, the question can also be put like this: can valid individual insecurities and interests be made secondary to valid concerns of vulnerable groups?

Since these questions are rooted in the dubious morality of prioritising interests of some groups to the exclusion of the concerns of the big groups, Scruton saw through the moral as well as political dangers of such an approach. He was of the view that, like all groups in a society, the majority “needs not only be not ignored, but it also needs to be respected”. As this could be easily misunderstood, here it’s important to clarify that he is asking for the majority to be “not ignored” and “ respected” only as much as other groups in the society. Even if Scruton argued so in the context of the British society and politics, it can be applied to any pluralist democracy claiming to accord equality to the concerns of all groups. In India, the importance of this insight in understanding some political developments as well as responses to them can’t be overstated.

More significantly, this prods us to fill a glaring gap in understanding the idea and practice of minoritism in pluralist democracies. The dangers of majoritarianism have been a subject of reflection, and rightly so, in a wide range of writings, most eloquently in John Stuart Mill’s phrase “tyranny of the majority” in his seminal 1859 essay On Liberty. The extent to which other currents – from imperialism to Nazism to Stalinism – can blend with a different kind of majoritarianism to produce totalitarian order can be seen in Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism.

Inevitably, even as the second half of the twentieth century saw intellectual currents and political forces in pluralist democracies build a consensus to avoid the dangers of majoritarianism, they strayed to the extreme of embracing different forms of minoritism. The common feature in these different forms of minoritism was appeasement – which mistook social justice for unreasonable concessions to minority groups. This process was sometimes also a part of electoral politics, as in India.

The extent to which such unreasonable electoral enticements could go was seen, for instance, in the 2005 Assembly election in Bihar. Khalid Noor, an Osama Bin Laden lookalike was used to draw crowds in certain pockets by two political parties – the Rashtriya Janata Dal and the Lok Janshakti Party. Ironically, the latter is currently allied with the Bharatiya Janata Party. A newspaper report narrated the importance the Osama look-alike had in the electoral campaign: “Noor was flaunted by both RJD chief Lalu Prasad and LJP boss Ram Vilas Paswan prior to the 2005 elections with an eye on the Muslim votes. ‘Osama’, the leaders thought, was politically saleable in Bihar. Noor’s seat in the helicopter was permanently booked with Paswan and Lalu Prasad, even at the cost of dropping other recognised political leaders. Noor, dressed in the Osama dress code, played to the gallery sharing the stage with these two leaders and attacking the US for its ‘anti-Muslim’ policies. In the 2005 February Assembly polls, Noor was with LJP chief Paswan who was then at loggerheads with Lalu Prasad and trying to woo away the Muslims from the RJD.”

Much before this, along with other factors such as the Ayodhya temple movement, the backlash against appeasement was seen as crucial to the rise of the right-of-centre political forces like the BJP in the late 80s. However, while the backlash might have provided the immediate political impetus, the party sought its ideological wellspring in the ideas of cultural nationalism and civilisational ethos blended with goals of development in a modern state system.

This was happening while the socioeconomic conditions of the largest religious minority community, Muslims, remained grim. The Sachar Committee report of 2006, presented under the aegis of the Ministry of Minority Affairs, showed the community lagging far behind in economic and social development indices. However, even responses to such findings brought with them a different form of backlash. In December 2006, addressing the 52nd meeting of the National Development Council, then prime minister, Manmohan Singh, said minorities, particularly Muslims, must have first claim on resources for meeting the goals of equitable development. This statement, obviously, spurred a backlash and invited the charge of appeasement.

The assumed moral argument of redistributive justice in giving primacy to the development needs of the minorities wasn’t acceptable to many. The “first claim’’ argument was morally dangerous, they said, as it subverted individual as well as collective claims of other groups in a pluralist democracy. Such a view wasn’t a votary of Rawlsian approach. However, opposition to the primacy of the claim didn’t mean opposition to state action in implementing the recommendations of the Sachar committee. According to government records, the status of the follow-up action on the Sachar committee’s recommendations was last updated in March last year.

Then, in the sphere of cultural and religious practice as well as inheritance, the Articles 25-30 of the constitution provided a range of religious freedoms to different groups and protection to cultural rights of minority groups. However, the larger question in India was always about how to approach the cultural inheritance, intrinsically linked to religion in many ways, and the public practice of religion by different groups.

Devoid of the cultural inheritance of its long past, India’s encounter with state-administered secularism was always going to be a mechanical application. Any scheme of national self-expression that excludes such a large part of its historical and cultural memory is set to be so. Even Jawaharlal Nehru, in moments of reflection, was aware of the tension that was lurking insidiously. Almost two years before the constitution was enacted, he posed these questions to the Muslim community at the convocation ceremony of Aligarh Muslim University in 1948: “I have said that I am proud of our inheritance and our ancestors who gave an intellectual and cultural pre-eminence to India. How do you feel about this past? Do you feel you are also sharers in it and inheritors of it and, therefore, proud of something that belongs to you as much as to me? Or do you feel alien to it and pass it by without understanding it or feeling that strange thrill which comes from the realisation that we are the trustees and inheritors of this vast treasure...You are Muslims and I am a Hindu. We may adhere to different religious faiths or even to none; but that does not take away from that cultural inheritance that is yours as well as mine.”

While reviewing a book, I briefly reflected on some other questions that cultural inheritance raises in its interaction with the secular state. However, there was another tension that was becoming obvious, with special provisions such as Article 25-30 placed as a point of juxtaposition. At what point would the assertion of religiosity by the majority community in the public realm be seen as majoritarianism.

The fact that a political stream was tapping into this confusion, if not anxiety, among the middle class followers of the country’s majority religion was also visible. In 2014, some scholars saw a cathartic point for it, though other factors were also significantly at work. The sociological underpinnings of such public statements were identifiable. “A generation felt that elite modernisation was a hypocritical affair conducted by groups which used words like ‘secular’ to dismiss the thought processes of a middle class more rooted in religion. By articulating such anxieties, Modi soothed their wounded subconscious,” sociologist Shiv Vishwanathan observed afterwards.

Another important sphere in which this hierarchy of group concerns and anxieties could be seen is when two different groups are either victims or perpetrators of physical violence or involved in a violent clash. Even though the numerical mismatch implies the majority inflicting more damage, it doesn’t mean the pain and anxieties of the victims of violence belonging to the majority community can be ignored. This is particularly relevant to the coverage of communal violence by a section of the news media.

The defence of selectivity with nebulous morality placed in the hierarchy of grievances and anxieties is a weak defence. The sufferers of violence – from any group – are exposed to fear and anxiety at group level as well as individual level. In fact, by being selective – or by practising tokenism – on either side of the divide, the news media only unwittingly contributes to another set of grievances and distrust. The question of equivalence and larger context can be part of analysis but that doesn’t mean downplaying or neglecting victims who have their own set of anxieties and fears.

In a year in which Scruton passed away, his insights find immediate use in countering some institutionalised and dubious “common sense”. That, however, also leaves the greater task of avoiding their distortions and understanding them only in the sense he offered them – nothing more, nothing less. Misunderstanding them would be a disservice to him.

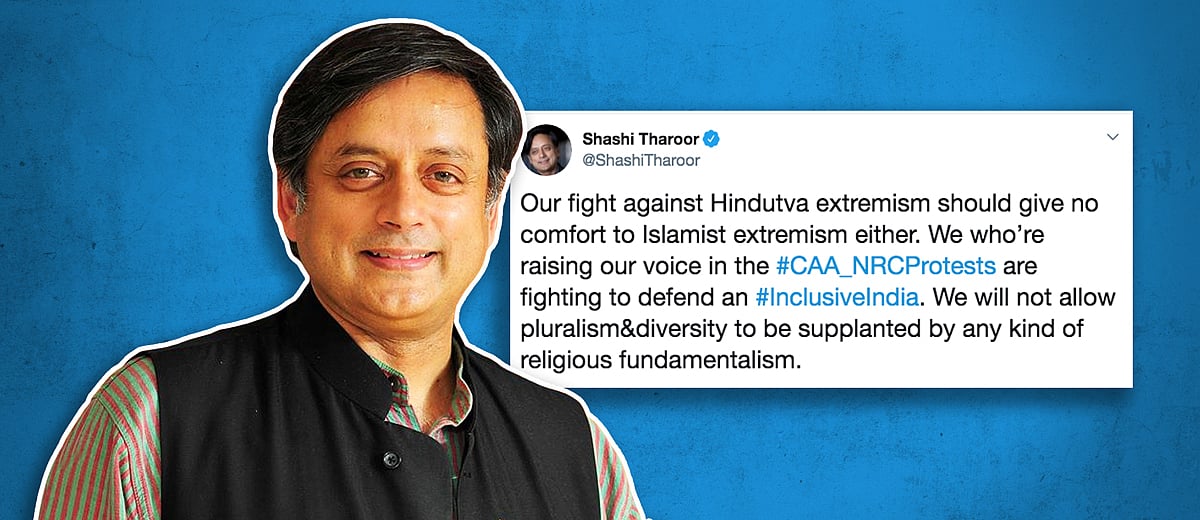

Shashi Tharoor and the majoritarian strain that afflicts Indian liberalism

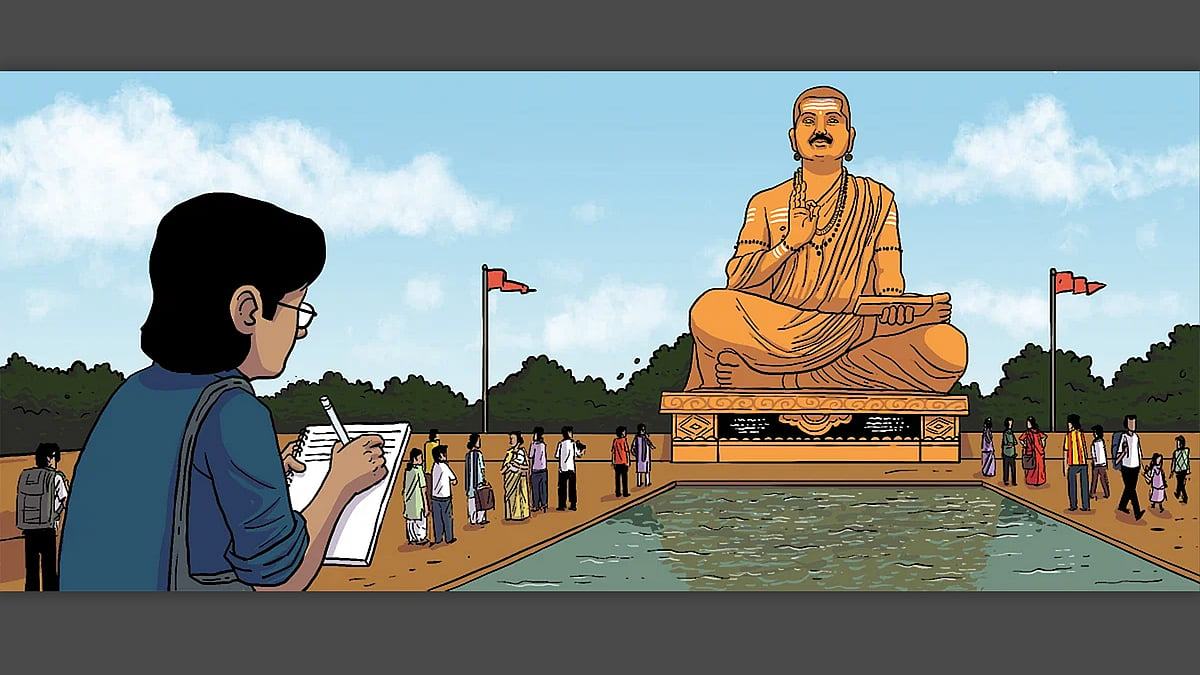

Shashi Tharoor and the majoritarian strain that afflicts Indian liberalism Finding Basava: The poet? Philosopher? Saint? Social reformer?

Finding Basava: The poet? Philosopher? Saint? Social reformer?