Dear ‘national’ media, stories on Assam floods must go beyond the one-horned rhino

The unjustifiable neglect of reporting on the Assam floods illustrates the continuing debate over what constitutes ‘national’ news.

It was the one-horned rhino that finally woke us up to the devastation caused by floods in Assam.

What began in early June finally reached "national" status, in that the so-called "national" media woke up to it, when the Kaziranga National Park was submerged almost entirely and the couple of thousand one-horned rhinos housed there had to scramble to find higher ground. Some of them did not make it. Over 100 wild animals, including at least nine rhinos, have died so far.

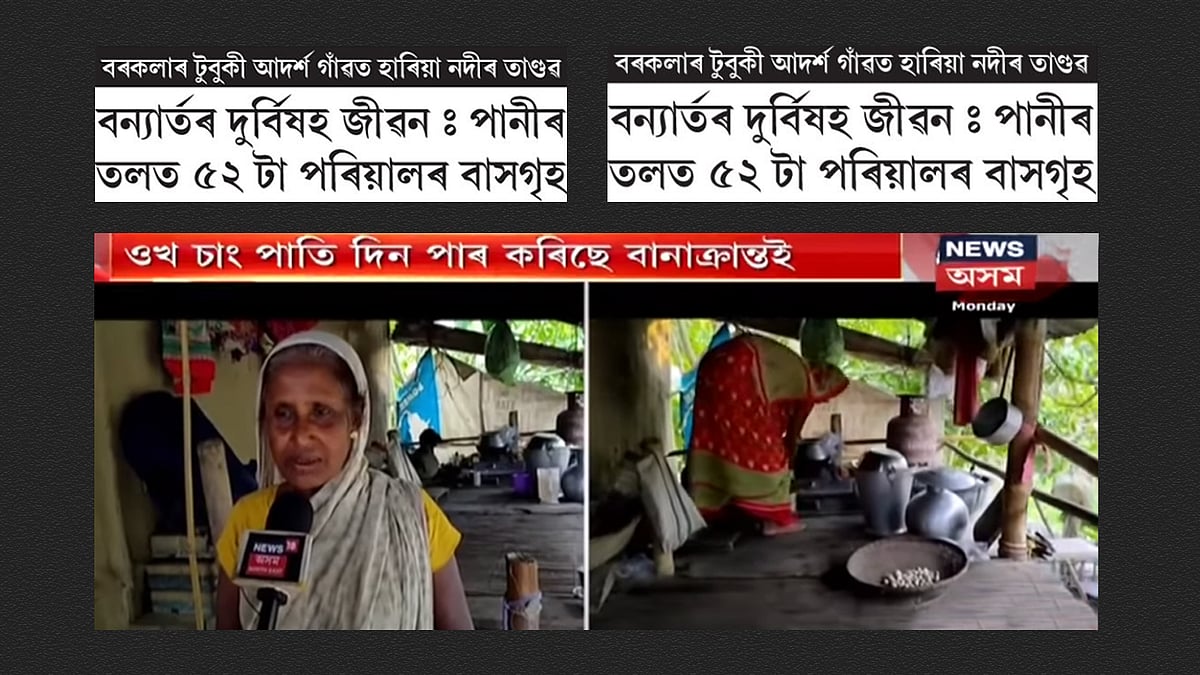

Many humans have also died, more than 100. The floods have affected an estimated 56 lakh people across 21 districts. Their homes were submerged or washed away, and thousands had to seek refuge in relief camps. Cropland, covering an estimated 128,000 hectares, has been destroyed. By all measures, this is a catastrophe on an enormous scale, worthy of attention.

Why then does it take weeks before the Indian media turns its gaze towards it? While it is true that floods are an annual occurrence in Assam and Bihar, is that enough reason to pay so little attention to the human and ecological tragedy unfolding? After all, almost every year, parts of Mumbai go under water during the monsoon. This year, so did parts of New Delhi. But they made it to the national news.

The unjustifiable neglect of reporting on the Assam floods illustrates the continuing debate over what constitutes "national" news. The Assamese have held a long and festering grievance against successive central governments and what they call the "mainland" media for ignoring their plight during the flood season. The floods are also inextricably entwined with the politics of the region.

Just by virtue of the scale of the current disaster, which is a combination of natural and ecological factors as well as developmental interventions over decades, the flooding in Assam is a big story. And the people who face the fury of the "mighty" Brahmaputra, an adjective automatically used to describe the river, deserve as much attention as the one-horned rhino. Yet, almost like clockwork, every year when the rhino faces imminent danger of drowning, the stories begin appearing in the national, and even international media. In the UK, the royals were putting out anxious statements about the plight of the animal.

While the damage caused by the floods is extensive, since the 1980s, people in Assam have felt that the flooding has worsened. Apart from the nature of the river, and the terrain through which it flows, the disaster has been compounded by human interventions and policies, such as deforestation in the catchment areas. Furthermore, the river brings down an enormous load of silt that accumulates, thereby raising the height of the riverbed in some sections. This is a direct consequence of the policy of building embankments to prevent flooding. These structures restrict the river, but when the river is in spate, it breaks through the embankments, or flows over them. As a result, the force of the water is far stronger and causes much more damage.

According to the "Floods, Flood Plains and Environmental Myths", published by the Centre for Science and Environment in 1991, an expert committee set up after the 1986 Assam floods had recommended that no more embankments should be built. Yet the policy continues, with successive governments spending crores on building and strengthening embankments in the mistaken belief that this will alleviate flooding.

What is evident is that the story of floods is not just about what happens when the river floods, but also previous policies that have contributed to the damage caused by this annual event. This context is often missing from most of the reporting on floods in general, and the floods in Assam in particular. It is reported as an event, not the culmination of several processes. As a result, we fail to understand why the extent of devastation appears to get worse every year.

There are exceptions, as always. Here, Scroll has done a service by assembling a reading list of previous and current articles on the Assam floods that place them in context. This article by Mitul Baruah is particularly useful in understanding why embankments have contributed to the problem, rather than being a solution. The other articles also look at another popular perception that dams control flooding when often they exacerbate it.

There's also a reason why the wildlife in Kaziranga is having such a tough time in recent years. That is because National Highway 37 runs right through it. Even when there are no floods, scores of animals are crushed under speeding vehicles when they cross over from one part of the sanctuary to the other. The highway was built despite strong campaigns by environmentalists against it. The current state government is now apparently planning to build a 36-km long flyover costing Rs 2,625 crore so that there is a corridor beneath for the animals to cross. Could there be a clearer illustration of environmentally blind developmental policy?

It is important for the media to bring out this background and context to what are seen as "natural" disasters, so that people are informed about how myopic and short-sighted policies also play a part.

Equally important is the question of what constitutes "national" news. This is relevant at all times, but especially now. People living in remote areas, or even not so remote, feel strongly about how the "nation" appears to be centered on the metropolitan cities and the Hindi belt. Even news from the south takes time to register in the rest of the country.

Today, the Covid-19 pandemic is playing out locally, but is also national and international. Yet, it is evident that without the detailed reports from the ground, people would not be able to relate to media reports about the pandemic, as my last column had emphasised.

In the post-Covid media scenario, with decreasing revenue streams that have already led to retrenchments of journalists in all forms of media, this question could take on greater significance.

For some time now, television news has defined "national" by its ability, or inability, to get a camera crew to do a story. Financial constraints have already replaced news bulletins with studio-based discussions. Print and digital news platforms still manage to cover much more of the country. But they will also face limits because of the economics of running media houses. As a result, they too might be compelled to limit the extent of reporting.

Meanwhile, local media outlets are also financially strapped and could face closure in the years ahead. One wonders how long a paper like Mylapore Times, featured in this interesting article in Newslaundry, or others like it in the rest of the country, will be able to keep their heads above water.

The trend of local papers downsizing or closing altogether has been visible in the US for some time. Margaret Sullivan, media columnist for the Washington Post, writes about this and the decline of one such paper where she began her career. She argues that local reporting actually strengthens democracy. It also provides a source for credible news. In its absence, rumours flourish.

And, of course, these days, with social media, the problem has grown exponentially.

Sullivan quotes a PEN America study of 2019 that has a resonance for us in India: “As local journalism declines, government officials conduct themselves with less integrity, efficiency, and effectiveness, and corporate malfeasance goes unchecked. With the loss of local news, citizens are: less likely to vote, less politically informed, and less likely to run for office.”

In the current situation in India, when there is no end in sight to the pandemic, when economic hardships have already hit the most vulnerable and are staring the majority of citizens in the face, when the severe cracks in our health infrastructure have become evident, and when the bankrupt nature of our politics is on full display every day, democracy will be further weakened if sources of credible and reliable news disappear because there is no finance to back them.

***

The media industry is in crisis. Journalists, more than ever, need your support. You can support independent media by paying to keep news free. Because when the public pays, the public is served and when the advertiser pays, the advertiser is served. Subscribe to Newslaundry today.

Assam floods: How the local media gave space for affected people to articulate their stories

Assam floods: How the local media gave space for affected people to articulate their stories