From ‘caste public’ to ‘bio public’: How social understanding of migrants has grown during the pandemic

Research points at shifting caste dynamics and social equations, both among migrant workers and among the people in their hometowns.

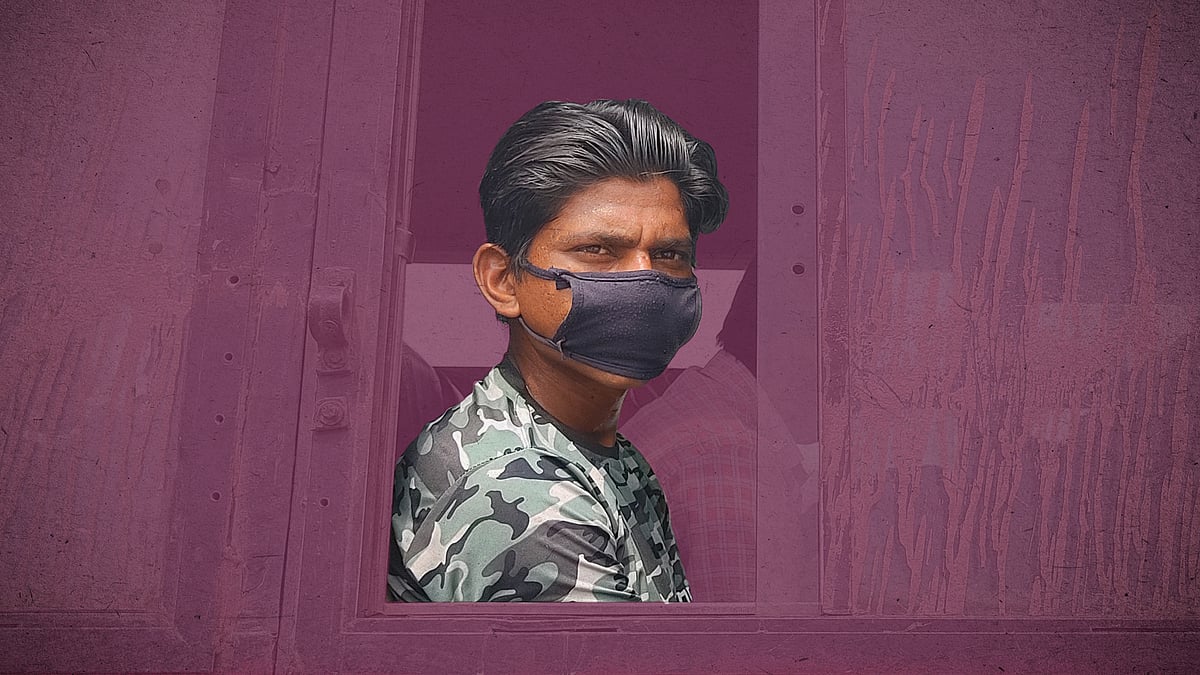

Migrant workers are yet again thronging railway stations and bus terminals to go back home in the midst of the second wave of the Covid pandemic. Even though the rush hasn’t reached last year’s scale, the signs of a repeat can’t be overlooked.

Media reports and images from big cities like Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai, and work hubs in Rajasthan and Gujarat, suggest that a sizeable section of the migrant workforce is finding ways to go home. Though there hasn’t been a national lockdown this year, the scramble to depart has been fuelled by state- and city-wide curfews coupled with apprehensions about the possibility of prolonged or more restrictions.

Only the next few weeks will reveal the degree to which this rush will replicate last year’s exodus and arduous tales. But with the social understanding of almost a year, it would be relevant to look at a few questions about the attitudes of the returning migrants, their motivations and constraints, and those of the people living in the places to which they are returning.

Watch: As Delhi locks down again, many migrant workers are heading home

Watch: As Delhi locks down again, many migrant workers are heading home Lockdown tales from three migrants: One who left and never came back, one who returned, and one who stayed

Lockdown tales from three migrants: One who left and never came back, one who returned, and one who stayedThe first set of questions could be: How do the returning migrants see themselves, as individuals or more so as a community, when they travel back home? Do social categories, already fragile in places of work in urban centres, further weaken under conditions of sudden movement or the stress of a biological threat? Does the experiential capital of the pandemic or the memory of suffering shape new ways of looking at social space? Do migrants begin to see themselves, even if temporarily, as a bio-community?

Also, how do the people living in villages and small towns see the returning migrants? Besides the economic, social and emotional factors, has the imperative of biological security against the virus become important in how the people look at those coming back home from far-off places?

In a country in which the last census showed 45.36 crore internal migrants, such questions become significant for grasping the social implications of a pandemic and the exodus. These questions have been addressed over the last few months by social historian and cultural anthropologist Badri Narayan, the director of the GB Pant Social Science Institute in Allahabad. Narayan’s research covered different districts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh – states that account for 14 percent and 25 percent respectively of interstate migration.

While looking at the responses of migrants from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh returning from cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Surat and Pune, Narayan examined the possibilities of a biological body emerging as a key concern in Covid-centred times and the relegation of other social categories like caste. Long-held perceptions about caste identities becoming weaker in the workplace of migrants was further reinforced during the sudden exodus back home. Even if temporary, the study showed that “bare life and the danger of losing it formed new social combinations and diluted social equations based on primordial identities”.

Narayan’s research dug into the memories of migrant labourers to have access to their experiential capital, which he simply defined as the remnants that the everyday social process leaves in people’s memories. One such process was constituted of the arduous experiences of migrant workers of all social groups – scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, other backward castes, as well as upper classes – and their stay at quarantine centres and eventual resettlement at their native places. Studying such experiences offers some clues to the emergent attitudes shown in a pandemic-stricken social setting.

In normal times, the anonymity of urban and work spaces, different settings, and the struggle for income has often meant the dwindling role of caste identities for migrant workers. They have found the mostly benign role of caste identities or have used them strategically in different contexts. They aren’t “rigid or assertive identities but operate as flexible and instrumental”.

In the extraordinary times of a pandemic, lockdown and exodus, this relegation was pushed even lower. For migrants returning from Mumbai, Delhi and Surat, Narayan found that the returning migrants seemed to bond over the common identity of dukhirayon ki jaati, or the caste of the miserable. For groups of migrants traveling together in a mix of upper caste, Dalit and OBC families, jaan bachave aur ghar pahuchne ki chinta – worrying about lives and reaching their homes – prevailed over other social considerations.

Even if the traditional discourse makes allowances for aapad-dharm as the wise point of departure from social norms during an emergency, the returning migrants grasp it as first-hand experience. When asked about the irrelevance of other social considerations during the exodus, a migrant youth replied: “Vipat ke maare ki kya jaat, bhaiya?” What does caste mean for those suffering a disaster?

But even more significant was the attitude of villagers to their protection against Covid overriding other patterns of social interaction. Narayan saw formative elements of a “bio public” in this process.

His research cited observations made in a village in Samastipur district of Bihar. A migrant belonging to an upper caste had escaped quarantine and returned to his village. A Dalit opposed it and was supported by upper caste villagers. Here, the need for protection from Covid became more important than caste.

Thus, one could see the slow shift from identities of “caste public” to “bio public”. The research recognised that this might be a temporary phase but it could produce experiential capital of suffering or fear which, in turn, could have a diluting effect on caste rigidities. This assessment was premised on the argument that shared sentiments in an emergency lingers in how people define themselves, and form part of identities in slow and invisible ways. That, however, would only coexist with long-entrenched social identities and self-perceptions.

Apart from these emergent attitudes in pandemic-related social settings, social scientists have also reflected upon the key motivations of those returning home. This includes efforts to understand the exodus beyond the obvious reasons of uncertainties emanating from loss of jobs and fear of curbs on other activities related to gainful employment. Important in this context is the perspectives in which sociologists like Dipankar Gupta have sought to see the socio-psychological drivers of migrant behaviour.

Citing examples and empirical observations from the current pandemic and other emergencies in the last four decades, such as the exodus of 1994 related to the Surat plague, Gupta argued that along with economic factors and, perhaps far more than that, the need to be with family and at home when faced with a life-threatening crisis was a key motivation in exodus behaviour. Most of them knew they were returning to people poorer than then but the appeal of a familiar milieu and the emotional pull of the succour was a strong driver of the movement back home.

“When faced with an imminent threat to life,” Gupta wrote, “the tug of home and family is much stronger for the industrial worker than the industrial glue that comes with an industrial occupation.” Identifying the value that migrants attach to the idea of home when looking for solace in times of fear, he continued: “When urban workers rush to their rural homes, it is because they fear a death where nobody prays for them more than a life where nobody prays for them.”

The current exodus of migrants to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar might be different in some significant ways, though. First, unlike the first wave of last year, the second wave of the pandemic has impacted both these states, Uttar Pradesh far more. That however, does not deter the exodus back home as the cities and states of their employment are still far more affected. Moreover, unlike last year, the fact that regular trains and bus services are still largely operational has made their return relatively less arduous. The one difference that is holding back the scale of last year’s exodus is that lockdowns are less stringent and shorter this year – something that many take as a signal for the revival of economic activities sooner rather than later.

Despite these factors, the general atmosphere of uncertainty might see more movement back home. In the light of recent studies on the emerging strands of bio public and other social constituents of migrant behaviour and the people in their hometowns, this phrase of exodus will throw more clues for the social understanding of a significant chunk of our moving workforce.