Gleaning social clues from news reports on the Gurugram quadruple murders

The social premises of the multiple motives intersect with the edge of private-public faultlines that surface in our neighbourhoods, perhaps even closer.

On the morning of August 24, Rao Rai Singh, 59, a retired army subedar turned property dealer, cleaned the road in front of his home in Sector 105, Gurugram. He then went to a small park that he had been maintaining, handed over its key to a neighbour, and asked him to take care of it.

Shortly afterwards, Singh walked to the nearest police station with a machete and confessed to hacking four persons to death, including a nine-year-old girl.

These are the details emerging from Singh’s alleged confession to the police and that of his alleged accomplice, his wife Bimlesh Yadav, 55. A few hours before turning himself in, Singh had purportedly used the machete to kill his daughter-in-law Sunita Yadav, 32, and his tenants Krishan Tiwari, 45, Tiwari’s wife Anamika, 35, and their nine-year-old daughter. The Tiwaris’ six-year-old daughter is the sole survivor and witness to the crime. Having temporarily lost her speech due to post traumatic stress disorder, she is currently undergoing treatment at Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital.

The neighbours got a sense of the bloodbath that took place only when a number of policemen arrived at the crime scene. TV news cameras and reporters soon followed.

Most neighbours expressed disbelief about the reported facts. In fact, Delhi editions of leading newspapers quoted neighbours recalling Singh as a helpful, jovial “tree man” who had done a lot of good in the upkeep of neighbourhood parks. That isn’t surprising: kothi-owners in Delhi and its suburbs in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh go the extra mile in giving landlords the benefit of the doubt. Some even believed Singh might have taken the blame to protect someone else.

Singh’s own admission suggested that he had planned the killings for a few days and even sharpened a machete for that purpose. However, the details – including the number of gashes and brutal cuts, the two rounds of hacking – seem like footnotes in the social register of the consumption of grisly tales next door.

The confessed, alleged and speculated motives for this crime are a microcosm of what drives a number of crime reports: Singh’s suspicion of an illicit relationship between his daughter-in-law and tenant, his eye on an acre of property inherited by the daughter-in-law, the dispute over rent agreements and non-payment of rent. The families of the victims attributed other motives in hindsight, but none of the motives explain the killing of all the victims. Even attributing it to the destruction of evidence sheds no light because the perpetrator intended to confess.

But the range of possible motives leaves some social notes.

First, even if the violent reaction to revelations of extramarital relations are a recurrent theme in crimes across different social settings, the other alleged motives behind the murders hint at precarious landlord-tenant ties in India’s urban centres. The dispute over a rent agreement and accusations about non-payment of rent aren’t strong enough reasons for the murders but point towards the fragility of rented housing and its weak social premises. The pervasive trust deficit between landlord and tenant has practically juxtaposed them as two classes in the social matrix of urban India. In fact, the purely transactional relationship hasn’t only dehumanised landlords and tenants as two living groups but has made cohabitation a tense proposition when both share different parts of the same building.

Second, even if such a trust deficit is spread across groups, the tenuous tenant-landlord relations are more visible with the influx of a migrant workforce and students looking for rented housing in metropolitan centres. A set of regional stereotypes and prejudices have only added to the frequent tensions between landlords and the steady flow of migrants to big cities. In Delhi-NCR, for instance, scanning the city news yields a regular supply of violent incidents rooted in such tension. In many such reported incidents, the workforce and students from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and northeast states find themselves at the centre of tenant-landlord discord.

Third, the fact that news reports linked the non-payment of rent to the loss of a tenant’s job during the lockdown suggests how issues related to paying rent have been an ignored stress-point during the pandemic. Researchers Mewa Bharati and Juhi Jotwani have argued that rent constitutes a major worry in urban settings. It isn’t true for only low income groups but even sections of the population that identify themselves as the urban middle class.

Fourth, the incredulity of Singh’s neighbours about the macabre killings next door, or even the doubts about the criminal tendencies of one of members of their own house-owning fraternity, shows insular denial. The inability to register the dark alleys of depraved selves in the midst of cosy settlements has been a case of the sociological exceptionalism with which urban middle class deludes itself with. They really don’t know about the people who might endanger them the most: those inhabiting the immediate surroundings. The dangers from the extended private space in the family, neighbourhood or your vehicles negotiating the road and other vehicles are far more than any danger of public sphere, institution and state that you endlessly argue about on social media.

Fourth, the banality of evil, to use Hannah Arendt’s phrase, hasn’t meant any dip in the interest that news consumers show in devouring every possible detail of the criminal landscape of everyday India. It isn’t surprising that crime shows on Hindi news channels as well as entertainment channels are at the top of viewership charts. However, even the supposedly national channels only intermittently extend their gaze beyond city crime. The same is true about how even broadsheet national dailies cover sensational crime, mostly city-centric and with granular details. The way the Gurugram quadruple murder case hogged front and city pages in Delhi editions of news dailies is as much an indicator of its shock value as much as it reflected the nature of its urban middle class readership. To add to that, it had elements of a social narrative unfolding as a gruesome crime, a reminder of a darker depravity lurking around the neighbourhood.

The social premises of the multiple motives attributed to the Gurugram hacking spree intersect with the edge of private-public faultlines that surface in your neighbourhood, perhaps even closer. Its shock value is more rooted in a lingering sense of collective voyeurism rather than improbability. The deluding denial of our depraved and dangerous selves only provide the solace of distance. That isn’t comforting enough, that’s closer than we think.

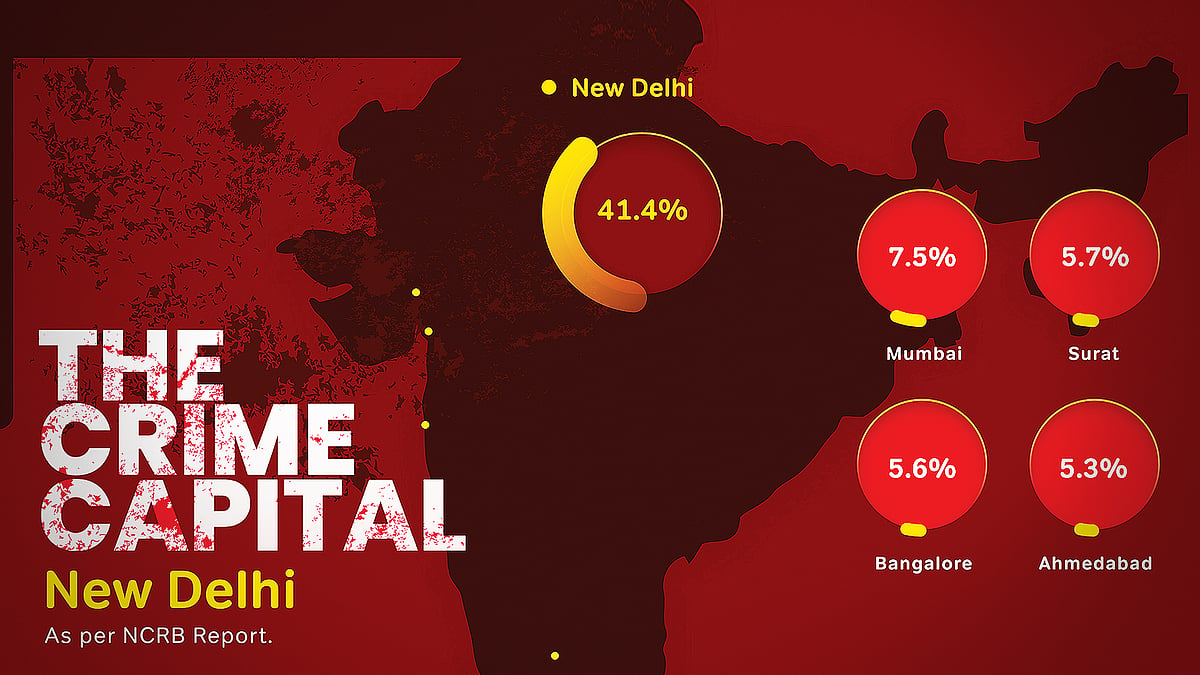

Why is Delhi India's crime capital?

Why is Delhi India's crime capital?