In Patrick French, the world has lost an important chronicler of lives

Writing aside, he played an important role as an academic and institution-builder.

It was in the second half of 1997 that I first came across Patrick French’s work. I was a bit late; French was already two books old by then. Oddly, I learned of his work through an interview with him published in the Sunday supplement of an English daily. It was barely a few weeks after the publishing of his second book, Liberty or Death: India’s Journey to Independence and Partition – a book that caused quite a stir for seeing the events, key figures and moves leading to Partition in a revisionist light.

The interview mostly focused on the themes and controversies that surfaced after French’s portrayal of this eventful, intriguing phase of history. I snipped it from the newspaper, tucked it into a file, and read my first Patrick French book.

I could have read him earlier. Only three years before this, his biography of Sir Francis Younghusband, the British explorer and army officer, had been acclaimed for its craft and diligent detailing. The wide-ranging material for Younghusband: The Last Imperial Adventurer (1994) came from French’s travels across central Asia. This was seen in how he reconstructed the remarkable explorations that Younghusband’s life left in its trail, including an early 20th century expedition to Tibet.

It’s unclear whether this period of travel and research or an earlier interest in Tibet was more influential in prodding French to write his 2003 book, Tibet: A Personal History of the Lost Land. The cause of Tibetan freedom remained one of his overt political interests, apart from a brief dabble in electoral politics in 1992 when he unsuccessfully contested the UK parliamentary poll as a Green Party candidate.

But in ways that he could hardly have foreseen for his writerly life, French’s handling of life-recounting material and the strands emanating from them made biographies his most remembered forte. To a great extent, his authorised biography of VS Naipaul (The World Is What It Is, 2008) brought French the well-earned reputation of being one of the most accomplished biographers of our times. As French wrote in his introduction to the book, bringing “the subject with ruthless clarity to the calm eye of the reader” was his aim while setting out to write such an account. Even with Naipaul allowing access to all the material, or perhaps because of it, it was a daunting task.

Biographies need a balance between “no job is too small” and avoiding the “tedious march of facts”, as James Atlas writes in The Shadow in the Garden: A Biographer’s Tale, while admiring Richard Ellman, his mentor in biography writing. French’s account of Naipaul managed to strike that space of equilibrium, with plenty of details while being aware of a biography’s limitations in chronicling a life and a lifetime’s work.

As an observer of social and economic factors at play in contemporary India, French was quite upbeat about the advent of India’s time under the global sun. In his 2011 book India: A Portrait, he wove his arguments around individual tales that, in a broader sense, were inferred to describe India as “a macrocosm and may be the world’s default setting for the future”. He peopled his book with voices that were classified to fit into each of the three sections of his work: rashtra (where he talked about the evolution of a nation’s political life), lakshmi (to share his arguments about economics), and samaj (where he talked about society and religion).

But French’s sanguine take on the India story didn’t go down well with everyone. It famously resulted in a literary spat with writer Pankaj Mishra who, in a scathing attack, accused French of glossing over deprivation levels in the country. He dubbed French “a Curzon without an empire”. French responded by arguing that Mishra’s was “more an ideological cry of pain than any honest appraisal of my book”.

This was, by no means, the last French wrote on India. The country engaged his attention and he reflected on it in the pages of newspapers and magazines. Sometimes, this led to a striking profile, such as this one on Arun Shourie; others could be accounts of chance meetings, such as the one he had with Afzal Guru in Tihar jail. Amid these sporadic writings in Indian publications, he also kept a keen watch on India’s print media space. One remembers him tweeting about how the Sunday pullout of Economic Times was a cut above the rest.

French’s writings could easily make one lose sight of an equally important role he played as an academic and institution-builder. He built on his university studies in literature at Edinburgh University to diversify into interdisciplinary pursuits, successfully pursuing a doctorate in South Asian studies.

That stood him in good stead when he was appointed the first dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Ahmedabad University in 2017. When he stepped down five years later in 2022, he looked back with the satisfaction of having built the institution from scratch, aptly chronicling its journey through two contrasting pictures that he posted on social media.

Even if his repertoire is far wider and more inviting, it’s apt that French’s last writing project was of ambitious scale – an authorised biography of British-Zimbabwean writer Doris Lessing. In tracing the arc of lives – literary or otherwise – French could deftly extend biographical accounts to many registers of selves and times lived. When turning his non-professional historian gaze to the past, he could put his rich material to use in engaging storytelling about the moves, motives and forces shaping history.

In a broader sense of the term, French was an important presence in the efforts of looking at the world, both past and present, with curiosity. He is lost too early at the age of 57.

Update on March 18: The quote from James Atlas has been corrected from ‘no detail is too small’ to ‘no job is too small’.

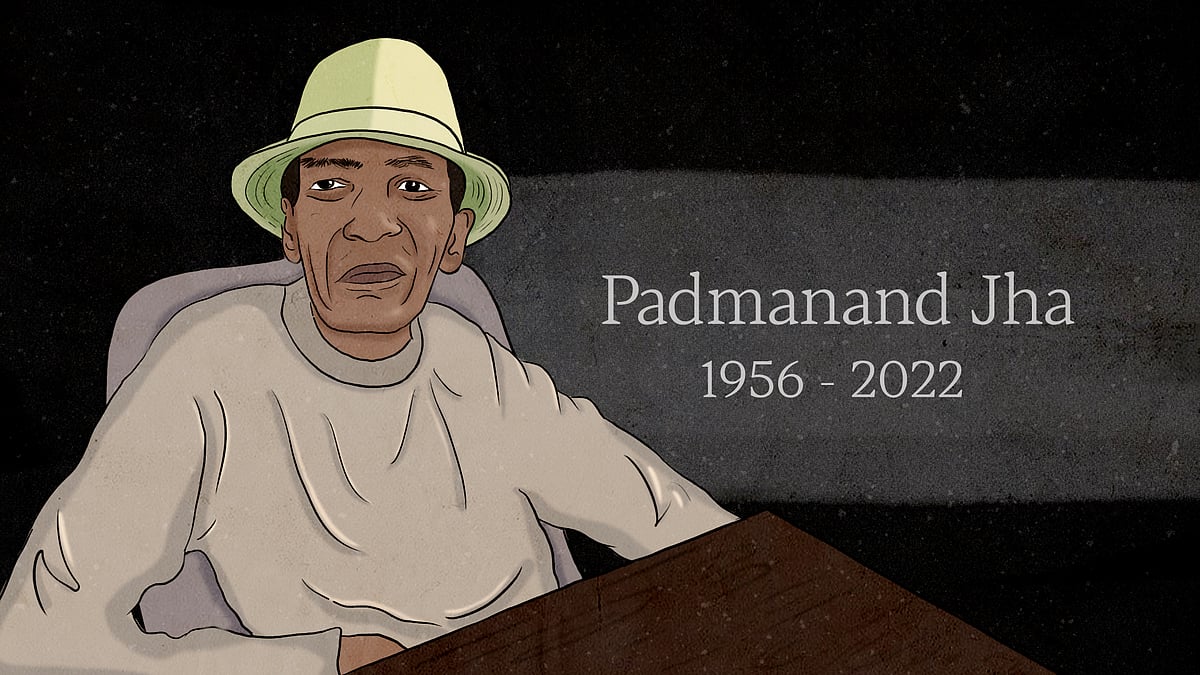

Padmanand Jha is no more. And Indian journalism is the poorer for it

Padmanand Jha is no more. And Indian journalism is the poorer for it