Explaining Operation Sindoor to my teenager, or why misinformation helps nobody

When journalists play the role of the state, they do us a disservice.

All of last evening, my 14-year-old, ridden with anxiety, pestered me for information on what was going on.

“Amritsar, Chandigarh, Srinagar, Jaisalmer – have they been bombed?”

“How would I know?” I asked. “And who is telling you this?”

Some of it had come via WhatsApp – that bane of parenthood – and the rest had been googled, and shared between friends.

“Don’t believe it,” I said. “Only the Army or the government has proper information, in warlike situations.”

But what about the videos all the kids had found online?

“I’ve seen them. Most are fake,” I tried to assure her. “And even the ones coming from Jammu are just anti-aircraft defence systems being fired.”

I don’t think I was successful in my attempt to be convincing. After all, most of the information and the video clips had come from mainstream news sites and channels. Why would a teenager repudiate such ‘unimpeachable’ sources and believe their parent? Even this morning, when I showed her the government and armed forces’ official statements on X, I was only met with begrudging acceptance.

The misinformation made many kids skip school today, because their parents had been swayed by what they saw on TV. Mine was reluctant to go, probably wanting to be near us in case Pakistan’s missiles fell closer home.

“How can the missiles come here? We have layers of air defence to stop that,” I explained.

“Well, why did they empty out India Gate last night, then?” I was asked. A news channel clip was produced to prove her point.

I countered with a tweet by a friend and ex-colleague, the award-winning journalist Saurabh Shukla, who quoted a top cop that this was “standard practice” and happened every evening. Cameras just happened to be there last night.

This is why I’m writing this piece, thanks to the nervousness that the continuous barrage of fake news generated in my child yesterday. Misinformation, and active disinformation, doesn’t help anyone. Instead, it is demoralising and creates panic.

There is no doubt that every conflict situation comes with a ‘fog of war’. After all, we are all human beings, and our national identity is one of the most important aspects of what defines us. It is very difficult to set one’s nationalism and patriotism aside, to cast an objective eye on what is happening on the ground. Even more difficult not to get carried away with the passion of the moment.

Journalists often convince themselves that they are part of the war effort. That it is their job to exaggerate ‘our’ wins and undermine the ‘enemy.’ It is easy to get carried away in such situations, and get a bloated sense of purpose. Especially when the camera is trained on you.

But that is not the only issue with reporting on armed conflicts and wars. Journalists often convince themselves that they are part of the war effort. That it is their job to exaggerate ‘our’ wins and undermine the ‘enemy.’ It is easy to get carried away in such situations, and get a bloated sense of purpose.

Especially when the camera is trained on you. And, you are aware, that millions of viewers are tuning in to listen to every word you have to say. It is easy to start believing that you have the right to fight an information war on behalf of the government and the defence establishment.

I understand this sentiment, because I have been part of newsrooms during Kargil and 26/11 – two of the most intense conflict situations India has faced since the 24-hour TV news cycle began in our country. The atmosphere is tense and heightened. You are constantly competing with other channels, worrying that they have broken important news, and you don’t have it. Many newsrooms fall prey to the urge to get the news first and broadcast wrong information.

Only established journalistic systems can stop excesses at such times. For instance, during the Kargil War, my old employer NDTV would broadcast important information only when it had been confirmed in the evening Ministry of External Affairs briefing.

We had to be even more cautious than newspapers, because government briefings about war and conflict are sometimes off the record. They are as official as an official statement would be, but the intricacies of geopolitics require that governments are left with an element of deniability. This is realpolitik.

So, back then it was possible for newspapers to publish information given by “highly placed sources”, but TV needed soundbites.

By the mid-2010s, these strict rules of television news had been discarded by some ‘guerilla’ channels looking for TRPs. They started pushing out ‘source’ based stories every night on prime-time news shows. While this enabled TV journalists to cover many more stories than they otherwise could have – think of all the ‘scams’ during UPA-2 – it also disrupted the discipline of news production in television networks.

Journalistic hubris is nothing new. I don’t even think there’s anything wrong with that. The best reporters are often people with a grand sense of self and the will to be the first with the news. Good editors and editorial systems keep them in check.

Over the past 15 years, we have seen a serious deterioration of editorial standards in legacy media. People who eschewed journalistic ethics to get TRPs, have risen up the newsroom ladder and now call the shots. Their cynical, instrumental, approach to journalism has helped them rise to positions of authority. Indeed, if they happen to read these words, they will most likely dismiss them as wokeish rantings of a loser.

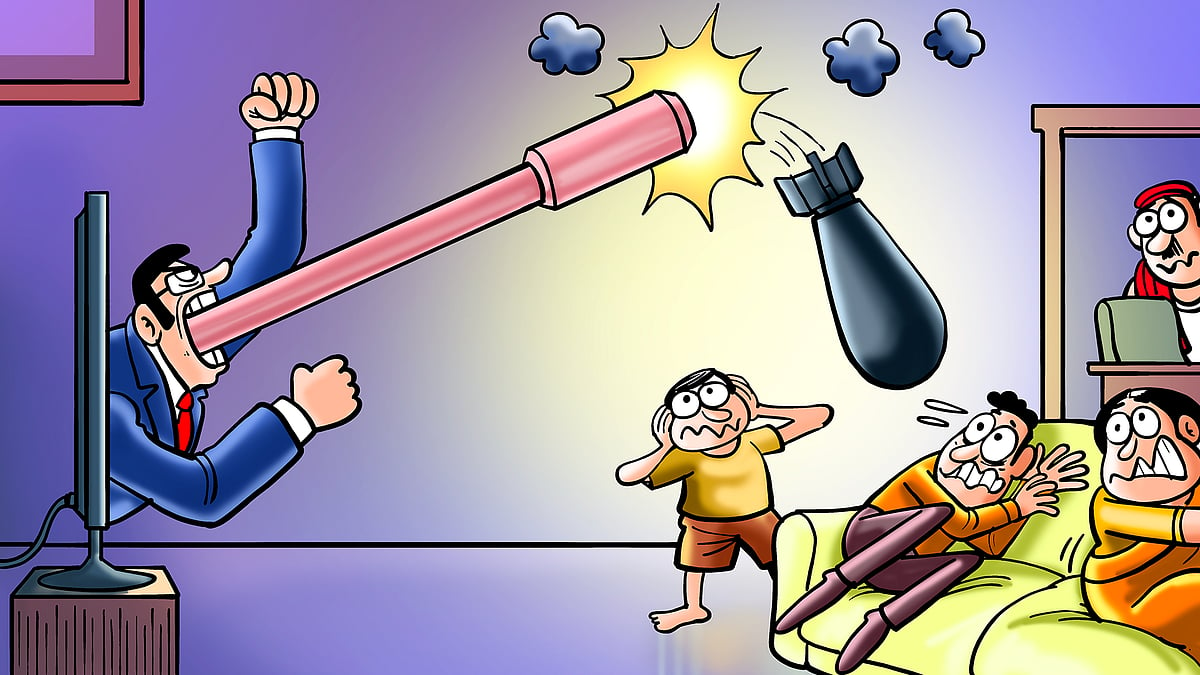

In such a situation, it is not surprising that we have such an intense fog of fake news emanating from TV studios. Where anchors screech out unverified news and then exult with bloodlust.

I hope this is just competitive imbecility, and not a deliberate decision to disseminate disinformation.

If these TV studio warriors believe that they are doing India a service by broadcasting fake information, they are overstepping their brief. It is not my contention that journalists should report whatever they see, without keeping the national interest in mind in times of war. However, it is not our job to take things in our hands.

If an information battle has to be fought with Pakistan, let the government do it. The people have elected it and given it the authority to do so. It is absolutely par for the course for ‘national’ news channels to report it as well.

When journalists try to play the role of the state, or consider themselves to be an extension of the national security apparatus, they do a disservice to the people.

That is when our children feel anxious, and worry about what tomorrow will bring.

In times of misinformation, we have got you covered. Click here to subscribe to Newslaundry.

India’s fog of war: Print media treads cautiously, TV media loses the plot

India’s fog of war: Print media treads cautiously, TV media loses the plot