2006 blasts: 19 years later, they are free, but ‘feel like a stranger in this world’

Newslaundry spoke to some of the men acquitted by the high court and their families to understand what it means to finally be declared innocent after losing everything.

Imagine your father being paraded naked in front of you and your acquaintances. Your 12-year-old son being slapped in the middle of the night. Your wife or sister being humiliated. Imagine yourself being stripped naked and subjected to months of brutal violence. Cut off from your loved ones for years, unable to perform your parents’ last rites, unable to see your wife, mother, father, or children. Imagine your children being mocked in school, their futures ruined, marriage proposals called off, and jobs lost, simply because they were related to you.

This isn’t fiction. This is what the men accused in the 2006 Mumbai train blasts say has been their lived reality. Of the 13, one was acquitted in 2015, after nine years in jail. The rest were acquitted nearly two decades later through a Bombay High Court verdict this month. For one of them, justice came too late – he died in prison in 2021, never living to hear the words “not guilty”.

That high court order was stayed this week by the Supreme Court after Solicitor General Tushar Mehta argued that it contained “certain findings of law” which would affect other trials underway in Maharashtra under MCOCA. But even as the Supreme Court put the ruling on hold, the high court’s findings have cast a shadow over the investigation, on confessions extracted through torture, and the fundamentally flawed way the MCOCA law was invoked in the first place.

Newslaundry spoke to some of these men and their families to understand what they endured over the years, and what it means to finally be declared innocent after losing everything.

Abdulla’s story: ‘My father died a terrorist in the eyes of the world’

Abdulla, son of Kamal Ansari – one of the 13 men accused in the 2006 Mumbai train bomb blasts – was only five or six years old when his father was taken away in the dead of night from their home in Basupatti, Madhubani district, Bihar.

“It was the night of July 19. Around 10 pm, about 18 to 22 men barged into our home. They were all in plainclothes. They weren’t even calling my father by the right name – they kept saying Kalam instead of Kamal. That night was the last time I saw my father outside a prison.”

Kamal was picked up without a warrant, without explanation. His family was kept in the dark initially, even about where he was being taken. “The next morning, a constable came to collect some of his clothes, but wouldn’t tell us anything,” Abdulla recalls. “My mother, grandmother and three siblings were at home. My youngest brother Sufian was just three months old. My grandmother and mother were in shock.”

Kamal’s arrest shattered the family’s foundation. “We were left with nothing,” says Abdulla. “My mother started working as a domestic staffer. My siblings and I had to drop out of school. None of us could study beyond class 10 or 12.”

The family was socially boycotted in Basupatti. “When I turned 10, some people in the village began taunting me, saying, ‘Your father is a terrorist, he did the bomb blast.’ This ostracisation was taking a toll on my family. We couldn’t take it anymore. In 2011, we left our village and shifted to Darbhanga permanently. We still avoid visiting Basupatti unless absolutely necessary.”

Over the years, Abdulla met his father only four times, last in Nagpur Central Jail in 2017. “He was kept in the Phansi Yard (death row barrack), and there was a transparent glass barrier between us. We had to talk on the phone, but the line was so unclear it was difficult to hear each other properly.”

“I had gone all the way there just to tell him that my sister was getting married. My father told me not to worry, and said that whenever he was going to see me next, he would give me a tight hug. But that day never came.”

The final phone call from Kamal came on April 2, 2021. “It lasted barely 30 seconds. He said, ‘Work hard, don’t worry, I’ll be back soon.’ But on April 19, he died of Covid in Nagpur jail. He never got to see the day the court cleared his name.”

“When we heard about the acquittal on July 21, it was the happiest moment of our lives – a moment we had waited for so long. I saw my mother smile like that for the first time in years, crying and smiling at the same time. My grandmother celebrated by distributing sweets across the entire village. But what still breaks my heart is that my father is not here.”

While speaking about the media’s relentless targeting of his family, Abdulla said, “When my father was arrested, a Hindi newspaper ran stories for nearly a month calling him a terrorist and the mastermind of the bomb blasts. The headlines were awful. After the acquittal, a reporter from the same newspaper came to interview my grandmother but she politely refused. She hasn’t forgotten how they vilified my father. And it wasn’t just that paper. Several news channels reported in the same sensational and irresponsible manner.”

“My father always believed he would be proven innocent, but he didn't live to see that day. He died with the tag of a terrorist, even though he was the son of an Indian Army veteran who fought in the 1962 war. That hurts the most.”

Asif Basheer Khan: The engineer who lost everything

Asif Basheer Khan, a civil engineer from a well-educated family in Jalgaon, moved to Mumbai in 2002 for better opportunities. Married in 1996, he was a father to three young children when his life took a devastating turn. In October 2006, Asif was arrested in connection with the Mumbai train blasts. He was 34 years old then. Now, after 19 years, he has been acquitted of all charges.

“I was not aware that we had a court hearing on July 21, 2025. That morning, around 8.45, a guard informed me I had to attend a video conference. When the honorable judge started saying that the witnesses were unreliable and mentioned the torture, I felt hope rising, because we had been saying this for years.”

Asif’s father passed away in 2011 while he was lodged in Yerwada jail. “He had cancer. I never got to see him again. By the time I got permission for his last rites and reached Jalgaon, he was already buried. That will haunt me forever.”

His voice falters when speaking about the humiliation his father suffered. “When he was admitted to the hospital, police officers told the doctor that he was the father of a terror accused. After that, everything changed – the doctor’s behaviour became rude and hostile. He was treated as if he was some terrorist, not a patient,” he claimed.

“My youngest daughter was just two years old when I was arrested. She’s 21 now. All through her school years, she kept a passport-sized photo of me in her bag, just so she wouldn’t forget my face. I missed watching her grow up. I couldn't attend the weddings of my elder son and daughter either.”

Asif claimed even the narco tests were “manipulated”. Referring to Dr S Malini who then worked at the forensic science laboratory, he alleged, “She used to threaten me, telling me if I didn't say what the police wanted, she would overdose me and I'd end up in a coma. The recordings of the narco tests were edited to suit the police narrative.”

“The torture I and other co-accused endured was beyond comprehension. I was stripped naked, beaten with sticks and belts, given electric shocks on my private parts. They threatened to bring my wife and mother into the lock-up and rape them in front of me if I didn’t confess. My brother was also brought in and tortured. All they wanted was a false confession. I never signed it,” he claimed.

Malini’s name resurfaced when the CBI accused the Forensic Science Laboratory in Bengaluru of tampering with narco CDs in the high-profile Sister Abhaya murder case. The Kerala High Court and a magisterial probe in Ernakulam both said the CDs were manipulated. In 2009, Malini was dismissed from FSL after allegations she had forged her educational certificates. She was later reinstated by the Karnataka High Court and the Supreme Court, which said she hadn’t been “given an opportunity to explain or counter the charges against her”. This case against her is pending trial.

Suhail Shaikh: The son who lived in secret

Suhail Shaikh, son of Shaikh Mohammad Ali Alam Shaikh, was just 12 when his father was arrested on September 29, 2006. “For the next 19 years, I tried to hide my father’s identity in school and college. In school, only a few close friends knew the truth. In college, no one knew.”

“Even though most people around me were decent, I was afraid they would not understand. I feared they would tease me as ‘the son of a terrorist’. My mother asked me not to reveal anything. She told me that if anyone asked, I should say my father worked outside Mumbai.”

Shaikh says that his father used to sell Unani medicines to earn a living. “He was the sole breadwinner. After his arrest, our lives plunged into hardship. My elder sister had to drop out of school after class 9. My mother started doing embroidery work to keep us afloat.”

“But stress took a toll on her health. At 33, she developed diabetes. In 2015, she was diagnosed with chronic tuberculosis and became critically ill. Thankfully, she recovered, but those years of struggle broke her spirit.”

Shaikh says harassment was a part of life. “Policemen would show up at our home regularly, even in the middle of the night. Once, at around 1.30 am, a large team of officers began banging on our door. We were terrified. When we finally opened it, they were enraged. One officer slapped me. This kind of trauma became routine for us.”

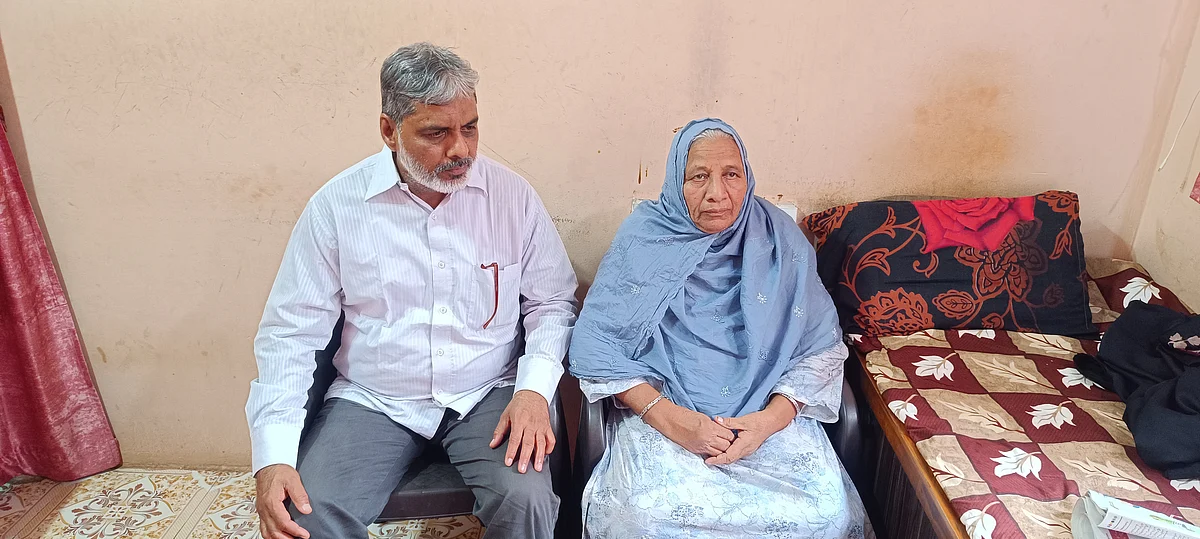

Mohammad Sajid Margub Ansari: ‘My daughter lost her childhood’

Mohammad Sajid Margub Ansari was 29 when police came for him. A computer and mobile repair technician, he ran a small shop in Jogeshwari. Today, at 48, he walks free after nearly two decades of being branded a terrorist.

He recalled his days in torture and how officials tried to frame him.

“I spent 34 days in police custody, four of which were illegal custody. The torture began the moment I was picked up. First, they stripped us naked. Then came the beatings with flour mill belts and wooden sticks. They’d insert an oil named Suryaprakash into our rectum and genitals. It gives an extreme burning sensation.”

“They made us lie on the floor. One officer would sit on our shoulders while two others would stretch our legs to a 180-degree split, then stand on them. The pain shot straight into our groin. I was urinating blood for days. I still suffer from vertigo because they repeatedly struck my head with those belts,” he alleged.

Ansari alleged that during the narco analysis at FSL Bengaluru, Dr Malini “did not just edit the videos, she physically tortured us too”. “She used pliers to squeeze my ears till they bled. She slapped me and threatened to inject me with HIV if I didn’t say what the police wanted…She would ask absurd questions like ‘What comes after six?’ When I said ‘seven,’ she slapped me, edited the question, and in the final video it appeared I had answered ‘seven’ to ‘How many bombs did you make?’”

Ansari says that he lost the person “I loved most” while he was jailed. “My mother died in 2014. She eventually became bedridden, waiting for me. I was allowed to attend her burial, but I never got to say goodbye….When I was jailed, my wife was three months pregnant. My daughter Mariam was born while I was in police custody. I never got to hold her. When she was little, she didn’t even come near me. She didn’t know me.”

“Once my wife wrote a letter to me in jail. She said Mariam saw another child riding on his father's shoulders. She went to a corner, sat down, and started crying. ‘When will my father come home?’ she asked. My daughter spent her entire childhood asking that same question.”

Recalling an incident at Mumbai’s Arthur Road Jail, he claimed, “In 2008, jail superintendent Swati Sathe falsely claimed that we had attacked the police. The truth is, she was angry because we were reporting how police officers were entering the jail and pressuring us to turn approver. She had us removed from our cells under the pretext of transferring us to other jails. Then she raised a false alarm and unleashed the jail staff on us. Heads were smashed, hands were fractured. We filed a complaint with the High Court…but nothing ever came of it.”

The court had ordered a disciplinary inquiry.

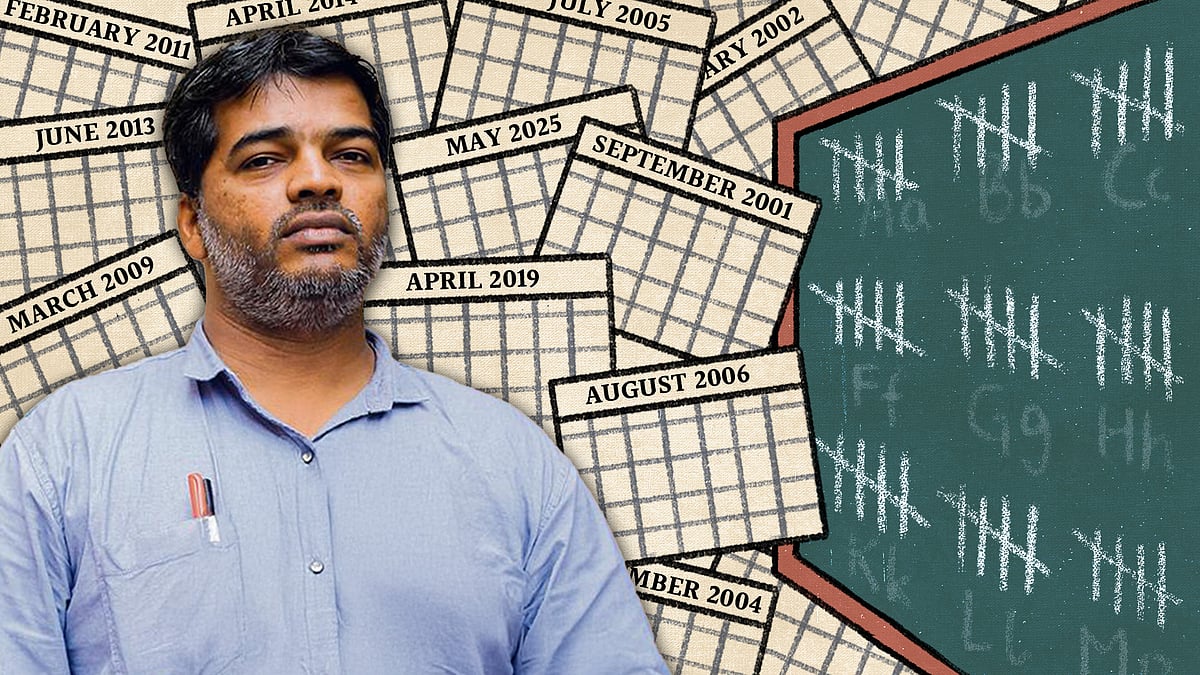

Ehtesham Siddique: From publishing house to prison

Ehtesham Siddique was just 24 when he was arrested. He had started his own publishing house in Mumbai – Shahdah Publishing – focusing on religious books. From Jaunpur district’s Yunuspur village, Ehtesham had moved to Mumbai for higher education. Today, at 43, he reflects on nearly two decades lost to wrongful incarceration.

Ehtesham had been married for just around seven months when he was arrested. “Now, after 19 years, I finally met my wife, Shabina. She waited for me all these years. Despite not knowing if I would ever come out, she chose to stay. Even when I told her once to forget me and move on, she refused. She said she’d wait, no matter what.”

Ehtesham shared one of the most horrifying incidents from his time in custody. “They brought in the father of a co-accused…He was an elderly gentleman. They stripped him naked in front of all seven of us and paraded him like that in the lock-up.” The co-accused, he claimed, agreed to sign a confession. “We were all crying. That image is seared into my memory.”

Despite the horror, Ehtesham didn’t give up. “I didn’t waste my time inside. I studied thousands of books and completed professional courses – an MBA in HR and Marketing, an MA in Political Science, and I’m currently completing my final semester of law school. I also read the Ramayan and the Mahabharat. I filed dozens of RTIs that helped us collect evidence to prove our innocence.”

Suhail Mehmood Shaikh: A spiritual healer who couldn’t heal his own wounds

“I was 37 when they arrested me. Now I am 56. I was young then and now I am old,” Suhail Mehmood Shaikh says with a bitter laugh.

A spiritual healer from Pune, Shaikh was picked up on July 21, 2006, and spent 86 days in police custody. At the time of arrest, he had three children – two sons and a daughter, aged 12, 9, and 8 respectively. Today, his eldest son and daughter are married. “They grew up without me. Their childhood vanished while I was locked away for a crime I didn't commit.”

Shaikh says that the police “got my family thrown out of our rented house in the middle of the night. Wherever they went, police harassment followed”.

His brother, a welder, lost all his contracts after police told his clients he was the brother of a terrorist. Another brother was fired from his job. His nephew was taunted at school for being related to a “terrorist”. Multiple marriage proposals for his family members were called off.

“I was offered Rs 25 lakh, a one or two BHK flat in Mumbai, and an assurance that they would settle me elsewhere if I turned approver against my co-accused. I refused. Later, the jail superintendent warned me: ‘This is jail. People die here. There are big gangs here who can make anything happen.’”

Shaikh claims the police broke his hand and leg. “My hip was dislocated. The beating was punishment for refusing to become an approver.”

What now?

Now acquitted by the Bombay High Court after nearly 19 years, Shaikh says, “The world has changed. I feel like a stranger in it. I see my children, but in my mind, they are still small. I can’t recognise many of my relatives or their children. I can’t use a smartphone. I even feel scared crossing the road alone.”

“But I am free. And I am thankful to the High Court for giving us justice for giving us our lives back.” He pauses, and then adds, “What hurts most is that I have always loved my country. I am a nationalist. Gandhi and Nehru were my idols. But I was branded a terrorist. That label crushed everything.”

Asif says he’s trying to reconnect with old friends and piece his life back together. “We always had hope. Now I want to live in peace, with dignity and help ensure what happened to us never happens again.”

Newslaundry reached out to Malini and Swati Sathe for comment. This report will be updated if a response is received.

2006 Mumbai blasts are a stark reminder of glaring gaps in terror reportage

2006 Mumbai blasts are a stark reminder of glaring gaps in terror reportage Acquitted in 2 cases, but a former terror suspect is a lifetime prisoner of suspicion

Acquitted in 2 cases, but a former terror suspect is a lifetime prisoner of suspicion