Gold and gated communities: How rich India’s hoarding fuels inequality

And how policies subtly reward this behaviour, perpetuating the wealth divide.

Jo bhi hai wo theek hai, zikra kyon karen

Hum hi sab jahaan ki, fikra kyon karen.

– Sahir Ludhianvi, Phir Subah Hogi, 1958.

Truth, when repeated often enough, starts sounding very banal. It just doesn’t register. Take this sentence: India is an economically unequal country. The evidence is all around us, and we seem to be totally fine with it. ‘It is what it is’ is how we rationalise inequality, with our in-built fatalism kicking in.

But is this rationalisation justified? Data says no, given that household wealth in India is concentrated in a very few hands. Analysts Manas Agrawal and Himank Sangai of the stock brokerage Bernstein point out in a recent research note that the top 1 percent of the households control around 60 percent of India’s total wealth. “Although growth will continue to create opportunities across the pyramid, we think the rich will get richer,” they further point out.

India’s top 1 percent controls 60 percent of all household wealth. But instead of building businesses, they hoard land, homes and gold – choosing visibility and speculation over risk and innovation.

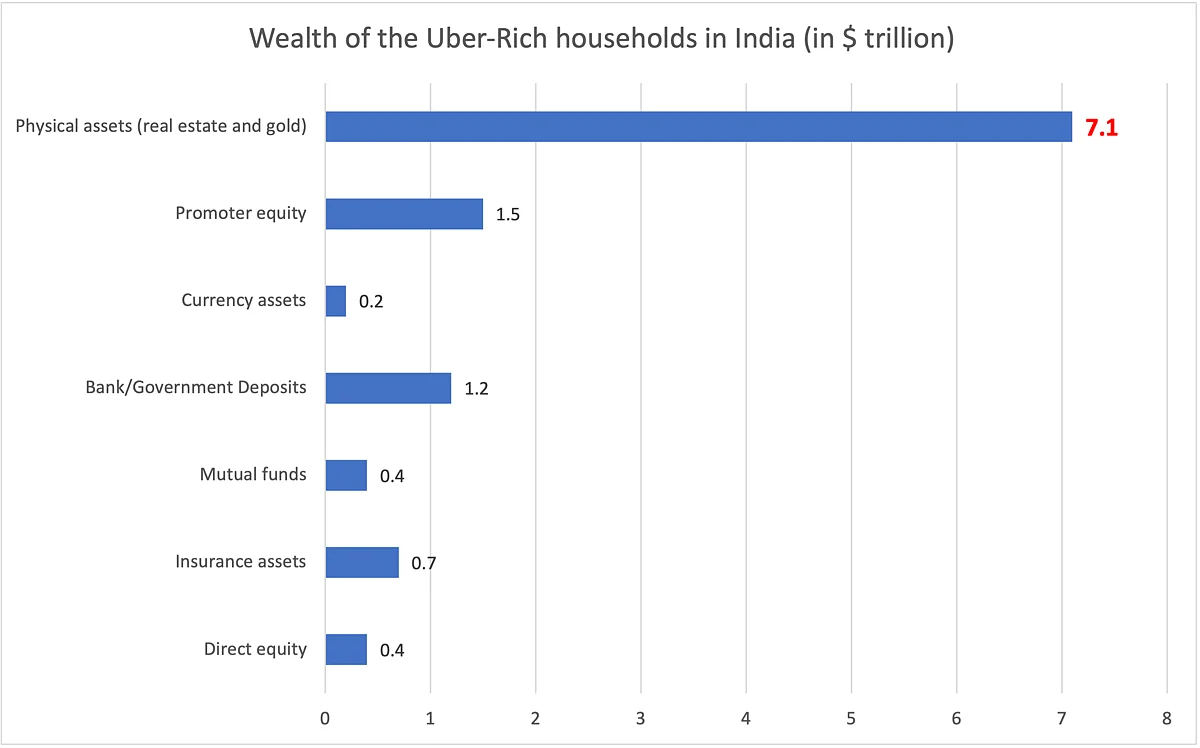

Indeed, India’s uber-rich – as Agrawal and Sangai refer to the top one percenters – own $11.6 trillion worth of assets. Of this, around $7.1 trillion is held in real estate and gold, $2.7 trillion is held in financial assets (non-promoter holding in stocks, mutual funds, insurance plans, bank deposits, government deposits), $0.2 trillion is held in currency form, and $1.5 trillion is held as promoter holding. A promoter is someone who starts a business and owns a significant portion of it at any point in time.

This data raises several interesting points.

First, 60 percent of the household wealth is owned by the top 1 percent, who also earn 30-40 percent of the total household income, suggesting huge income and economic inequality.

Second, of the $11.6 trillion owned by the uber-rich, $7.1 trillion is held in real estate and gold. Real estate could possibly mean land, homes, apartments, and so on. This implies that more than 60 percent of the wealth of the uber-rich is held in physical form. (Makes you wonder why the business media barely talks about this wealth and keeps plugging the stock market instead.)

Third, the richie-rich like to hold their wealth in physical form. Why?

Being rich is not just about being rich, you need to be able tell the world about it as well. That is not possible if the bulk of the wealth is in stocks, insurance policies, mutual funds, and bank deposits. To show off, one needs to own homes, land, apartments, and gold jewellery. These can become a talking point in the community, which owning financial assets rarely can.

This also explains why so many individuals in the business of managing other people’s money (OPM) invest heavily in real estate. Other than being a diversification of their overall investment, it also projects how rich they are.

Further, given that not all the uber-rich become rich through legal means, they need to be able to park their black money somewhere. Real estate and gold are excellent ways to hide black money and see it grow as well.

Fourth, and most importantly, on the whole, the uber-rich do not like the idea of investing in a business and building it. Maybe this comes from experience – the fact that running even a small business in India is very complex and difficult.

Dealing with different government inspectors and putting up with a large amount of paperwork, while trying to run a profitable business in an extremely uncertain environment, remains challenging. Or maybe there aren’t enough decent, viable business opportunities going around.

This has led to a situation where the ultrawealthy just like the idea of putting their money in real estate and gold, which are both speculative assets. This explains why the uber-rich hold real estate and gold worth $7.1 trillion, whereas promoter’s equity – or the total amount of capital invested in business – is at a significantly lower $1.5 trillion. They find it easier to speculate than to invest and build things.

Fifth, at a broader level and among other things, this also explains why private investment in the economy hasn’t really taken off over the years, with the uber-rich being more interested in speculating than investing. This, in a way, is also evidence of the mercantile nature of the Indian business class and the fact that the ease of doing business in India is resting in peace.

Sixth, as I had written in an earlier column on Newslaundry, it also explains all the talk in the media about premium and super-premium apartments selling for huge, never-before-seen prices – a game of passing the parcel being played amongst very few uber-rich.

Indeed, this has disrupted the overall real estate market, with the bigger builders – who can operate at some scale – being interested only in building expensive homes or gated communities, as they are called these days. The entire idea of building affordable homes for people to live in has gone out of the window.

Of course, with premium and super-premium apartments selling at the prices that they are, this establishes new price benchmarks across the broader housing market – what psychologists and economists call ‘anchoring’.

Individuals who had earlier bought homes to speculate in, start believing their properties are now worth much more. They become ‘anchored’ to the idea of higher prices, influenced by the media buzz and rising market reports, leading to a situation where these apartments don’t sell easily, and many can’t buy homes to live in.

Vast parts of the Indian real estate market are in a weird situation – they have low supply along with low demand, simply because the price points sellers want due to the anchoring that has happened in their minds, are not the price points that buyers can afford.

Seventh, economic inequality doesn't stay confined to household balance sheets – it finds its way into policymaking as well.

When a very small percentage of the population owns a major part of the country’s wealth, they also tend to capture a disproportionate amount of influence. This essentially leads to policies – particularly tax policies – often being shaped in the interest of capital, not citizens. Over the years, India’s income tax policy has favoured the non-salaried rich, with low capital gains taxes, no inheritance tax, and frequent amnesties for black money holders. It also needs to be said that this situation has improved at least on the capital gains front in the last few years.

Eighth, government policies encourage real estate speculation. Factors include lower tax rates on capital gains, lax oversight of unreported transactions, which encourages profits from real estate to be reinvested into more real estate, the lack of publicly available comprehensive real estate data, and infrastructure spending that disproportionately favours car usage over public transportation. Together, these factors help fuel real estate bubbles, drawing increasing amounts of money from the ultra-wealthy.

Ninth, with the top 1 percent holding 60 percent of the household wealth, it helps market India as a great consumer story. The luxury brands are expanding, premium car sales are rising, and as some of my friends often like to point out, malls in metros are perpetually packed.

But as I have often said in the past, these signals are misleading. What we are seeing is not a huge consumption story, basically, but top-heavy consumption, where a small, minuscule part of society, which is doing well, is helping in powering a false narrative of booming demand.

Tenth, wealth inequality becomes dangerous when it becomes entrenched across generations, which seems to be happening in India.

Given this, children of the rich inherit not just wealth, but also elite education, social and economic capital, and most importantly, access to opportunity, making the idea of social mobility an increasingly hollow idea.

Inequality in India isn’t just economic – it’s behavioural, institutional, and increasingly generational. The rich aren’t investing to build; they’re speculating to preserve and flaunt, because that’s how their incentives have stacked up.

Meanwhile, policies subtly reward this dynamic. Until India rewires its incentives – favouring productive enterprise over passive hoarding – the economy will remain imbalanced.

Vivek Kaul is an economic commentator and a writer.

If you liked this piece, let our reporters tell you why you should subscribe to Newslaundry.