How booth-level officers in Bihar are deleting voters arbitrarily

An analysis of 200 booths, along with interviews with 17 BLOs and 100 individuals – either voters who were removed or family members of those who were – reveals that highly inconsistent procedures were followed for these deletions.

Jhurana Das made Bihar her home more than four decades ago. She moved to the state as a 23-year-old bride. It is where she built her life, and it is where she lost her husband to a kidney ailment last year. Now, as Jhurana approaches 70, she has to prove that she is a legitimate resident with the right to vote.

In August, a Booth Level Officer (BLO) informed Jhurana that she may not be able to participate in the state’s upcoming polls. “I voted in the last state election,” she told us, as she sat outside her hut in Belauri, a locality on the outskirts of Purnia city in northeastern Bihar.

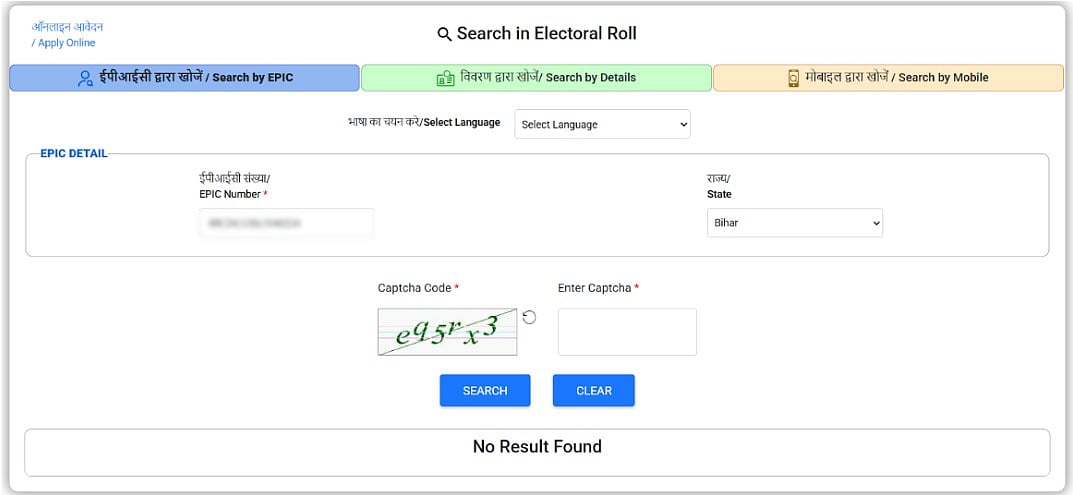

Jhurana’s name was missing from the draft electoral rolls that the Election Commission of India (ECI) released last month after it concluded the contentious Special Intensive Revision (SIR)—an exercise aimed at verifying the eligibility of nearly 80 million voters in Bihar. But her name doesn’t feature in the list of deleted voters’ that the ECI published after a Supreme Court directive either. Every time we entered the Elector Photo Identity Card (EPIC) number assigned to her, the website threw up an error message: No Result Found.

The BLO told Jhurana that she needed to procure her parents’ identity documents to re-register. Her parents, who are no more, lived in her native village in West Bengal, nearly 100 kilometres away. Ferrying those documents is a near-impossible task, financially and physically. Jhurana no longer works, given the constraints of her age— both her sons are tied up with the odd jobs they depend on to get by.

It is unclear why the BLO made this demand, when according to the ECI’s guidelines for the SIR, voters like Jhurana—who was born before 1987—are not required to submit proof of their parents’ Indian citizenship. (We were unable to reach the BLO who spoke to her, this copy will be updated if he responds.)

Parth Gupta, the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) for Purnia, who is overseeing the booth, acknowledged that Jhurana should not have been asked to furnish these documents. “Please provide her details and I will look into it,” he said.

Jhurana is determined. “I have asked my nephew to collect the documents and bring them to me,” she said. “I want to cast my vote at any cost. I am a citizen of this country.”

In June 2025, when the ECI announced the SIR—just a few months before Bihar is scheduled to go to polls—it claimed that it wanted to ensure “no eligible citizen is left out while no ineligible person is included.” Cases such as Jhurana’s reveal the pitfalls of the hastily-implemented process.

The draft electoral rolls published by the Election Commission exclude 65 lakh voters. Our analysis revealed that 200 booths across 58 constituencies in 26 districts recorded unusually high deletions—the names of between 324 to 641 voters were deleted in these booths. Since the ECI capped the number of voters for each polling station at 1,200 in Bihar, this means that at least a third of voters were deleted at every booth, and in some cases, as many as half. In total, 77,454 voters were deleted across the 200 booths.

According to the ECI’s electoral rolls manual, when more than two percent of the voters in a booth are deleted or if more than four percent have been added, election officials have to activate ground verification protocols. Gupta, the ERO, told us that Additional Electoral Registration Officers (AEROs) and BLO supervisors were undertaking these checks in Purnia.

Our team visited 10 among the 200 booths in three constituencies—Purnia, Hajipur, and Digha—and interviewed 100 people: voters who had been deleted, or family members of those who had. The ECI has excluded voters for four reasons: because they had died, migrated permanently, were registered from multiple places, or were absent. Most voters we met had been marked either “absent,” or “shifted,” even though they had been residing at their addresses for many years. Several claimed that their BLOs didn’t even visit their homes even though the ECI categorically stated that the SIR would involve “house-to-house verification.”

Our interviews with 17 BLOs—three in person and 14 over the phone—across nine constituencies in East Champaran, Vaishali, Patna and Purnia districts showed that there was no consistency in the process they followed to delete voters. This is because there was no standardised process to begin with.

The voters who have been deleted are scrambling to regain their rights. They are chasing after BLOs—many of whom are already swamped in the wake of the SIR—to understand why they have been deleted, and are trying to gather enough documents to mount a credible case for their inclusion.

According to the BLOs we interviewed, once the ECI announced its decision to undertake the SIR, EROs and Additional Electoral Registration Officers (AEROs) conducted about five to six formal training sessions for BLOs of each constituency. These sessions were focussed on procedures to verify voters, the BLOs said. They did not include any written or formal guidelines on the documentary or testimonial evidence that a BLO was to depend on before determining that a person was dead, shifted, absent, or already registered and taking away their right to vote.

During these training sessions, the BLOs were asked to verify the requisite details for those they were removing from the draft electorate rolls at their discretion, Gupta, the ERO told us. “Personal satisfaction of the BLO is…sufficient,” he said. For instance, If death certificates were available for voters marked for deletion because they were deceased, then it was “well and good,” Gupta added. But if not, the BLO could also ask people around to confirm that a particular voter had died.

This meant that the BLOs we interviewed applied their own, varying standards. Some conscientiously checked their claims and maintained records, others depended on hear-say. The integrity of this process appeared to be dependent on the integrity of the individual.

Vijay Kumar, the BLO of booth number 21 in East Champaran’s Raxaul constituency, told us that when he didn’t know what to do in cases of voters he couldn’t trace, he asked his supervisors for advice. “Jo karna hai kijiye,”—Do what you feel like, they responded, he said.

The voters who have been deleted are scrambling to regain their rights. They are chasing after BLOs—many of whom are already swamped in the wake of the SIR—to understand why they have been deleted, and are trying to gather enough documents to mount a credible case for their inclusion.

The SIR has already been subject to widespread criticism for its approach. The list of eleven documents it initially allowed as proof—such as passports and birth certificates—tended to favour the well-off. After multiple Supreme Court directives, the ECI directed the Chief Electoral Officer in Bihar to accept Aadhaar cards as the twelfth document a voter can produce as identity proof.

Our interviews revealed that the reinstatement process is further disenfranchising poor and marginalised voters, most of whom do not have the luxury of leaving their work to run from pillar-to-post and ensure their inclusion.

BLOs adopt ad-hoc approach

The BLOs told us that they distributed two forms door-to-door to every voter during the verification process. These forms listed the voters’ information—their EPIC ID, name, address, age, gender, constituency, booth, and photograph—as it was recorded in the ECI’s pre-existing voter rolls. Voters then had to sign a declaration affirming their stated address, their age, and Indian citizenship, as well as provide documentary proofs for each of these categories. The requirement for citizenship proof varied, depending on when they were born and whether or not they had been included in a previous electoral roll from 2003.

Once voters submitted the verified forms, BLOs entered their details on a phone app the ECI had asked them to use. Voters who didn’t submit their forms, or submitted documents deemed insufficient, were struck off the list. The BLO had to enter one of the four reasons outlined by the ECI for every voter they deleted.

A sub-divisional officer then sent a notice to the homes of voters who had been deleted and could be located, Gupta said. However, if voters “could not be found,” and no information could be obtained from family members or neighbours, no notices were issued. In some of these cases, BLOs stuck a sticker on their doors, Gupta added.

When the BLOs were unable to locate voters, they adopted different methods. A few made repeated attempts to trace the voters and devised fact-checking procedures of their own, while others seemed to have made no efforts to verify their claims at all, even by their own admission.

EROs and AEROs are meant to scrutinise submitted forms. This is an uphill task. “Between 1 August and 1 September, 243 EROs and 2,976 AEROs are expected to evaluate over 72 million forms, which comes to around seven hundred forms per person per day,” a report in The Caravan pointed out. “Assuming they work twelve hours a day, they would have a minute to look at each form and determine whether the applicant has satisfactorily proven their citizenship status.”

Some cases are straightforward—such as women who were registered from both their natal and marital homes. In such instances, the BLOs simply had to ask which address the voter wished to retain.

But when the BLOs were unable to locate voters, they adopted different methods. A few made repeated attempts to trace the voters and devised fact-checking procedures of their own, while others seemed to have made no efforts to verify their claims at all, even by their own admission.

In two instances, we found that BLOs didn’t even do the verification work themselves—they delegated it to their family members instead. These relatives confirmed to us that they had not attended any training sessions.

Gupta, the ERO, said that the BLOs were not permitted to delegate their work but “if BLOs are seeking the help of someone, and if they are present with that person, then that is allowed.” The workload, he added, was immense, so it was understandable if the BLOs required assistance, but they could only solicit logistical support.

One BLO shifted the onus onto voters, suggesting it was their responsibility to ensure they were not deleted. Shiv Kumar, BLO for booth number 377 at Digha constituency in Patna district, told us that it was difficult to conduct the door-to-door checks mandated by the ECI because in many cases, voter addresses were recorded incorrectly and their mobile numbers weren’t mentioned on their EPIC cards. (A little over half of Bihar’s residents use phones, according to information provided by the state’s chief secretary late last year.) Over 350 voters have been deleted in Kumar’s booth—only one has filed an application for inclusion so far. “I fail to understand why there is no interest,” Kumar told us. “It is their duty to come for inclusion.”

Some BLOs relied on their own know-how. “I live in the village, I know who has died, who has moved,” Ravi Kumar, the BLO of booth number 277 at Sugauli constituency in East Champaran told us. Sadrul Hasan, the BLO of booth number 8 in the same constituency adopted the same approach. When we asked him if he recorded any documentary proof or testimonies to substantiate his declarations, he said: “I didn’t. I know them personally, what further proof do I need?”

Even BLOs who tried to devise safeguards against arbitrary deletions adopted a spectrum of practices. For instance, Mohammad Samshuddin, the BLO of booth number 300 at Dhaka constituency in East Champaran district, told us that he travelled door-to-door to verify voters. When he couldn't find someone he spoke to other residents to determine their whereabouts.

Om Prakash Gupta, the BLO for booth number 158 in Pipra constituency, also in East Champaran, relied on documentary evidence. He collected death certificates for the voters he marked as deceased, he said. If such certificates were unavailable, he asked family members to provide a written declaration confirming that the particular voter had died. Two of the BLOs we interviewed said they had kept copies of documents—such as death certificates or family declarations on forms for voters marked as dead, absent, or shifted—for their own legal protection.

We asked 14 of the 17 BLOs we interviewed to explain how they verified the reliability of information provided by family members or local residents when they declared a voter dead, absent, or permanently migrated. None of them had an answer. All of them said that the ECI had not provided them with any specific instructions for such a scenario.

Disenfranchised voters in panic

Among the 200 booths we analysed, a majority of the deleted voters—44,139 people—were declared “shifted,” meaning they had moved out of their address permanently. Then were those declared “absent,” that is, the BLOs couldn’t locate them: 22,259 people. In addition, 8,582 voters were declared dead while 2,204 were found to be registered elsewhere.

About half the voters from the four districts we visited claimed that the BLOs in their respective areas had not conducted the physical verification checks mandated by the ECI. Many of these voters were marked “absent,” or “shifted.”

Jumaira Khatoon—a domestic worker in her sixties, who resides at Digha in Patna district—was struggling to reverse the deletion of her son Lalan. He is a migrant labourer who works at a tyre factory in Mumbai, and returns home twice or thrice a year, Khatoon told us. The reason for his deletion was that he was “absent,” she said. The family had been living in the same house for more than 50 years, and Lalan had voted from Bihar in the general elections last year, as well as in the Bihar assembly elections of 2020, according to Khatoon. The BLO did not contact Lalan’s family to confirm his eligibility, she added.

Vimla Devi, the BLO of the booth at which Khatoon and her family are registered, said that it was not easy to knock on every door during the SIR. Devi could not recall whether or not she had visited Khatoon’s house. As many as 60 voters, whose names were deleted from the draft electoral rolls, had applied to be included, she said. “We are working to correct it.”

Khatoon can neither read nor write. “I am now trying to get him registered again, but it is a huge task,” she told us. Authorities asked her to provide a residential certificate for the home she lives in as part of the documents to ensure Lalan’s inclusion, but she doesn’t have one. “I had to request somebody else to fill up the form,” she said. “My son was born here.” Khatoon had his Aadhar, voter card and ration card—of these, only the first is currently valid as a proof of identity.

Upender Pandit and his wife Prem Sheela Devi—residents of Baghmari, a neighbourhood in Vaishali district’s Hajipur constituency—have both been deleted from the draft electoral rolls for two separate reasons. Pandit was listed as having “shifted,” or permanently migrated, while Devi was deleted because she was “absent.”

“We haven’t gone anywhere,” Pandit told us. He recounted that the BLO for his area visited their home on July 1, and that he and his wife had both submitted the requisite documents.

Upender Pandit belongs to the Kumbhar, or potter, community, which comes under the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. Pandit left the traditional pottery work he was engaged in because he couldn’t make ends meet. He ferries people around town on a hand-cart to earn a living of about Rs 4,000 per month. Pandit cannot afford to take time off work to secure voting rights for his wife and him. “It is difficult enough to manage my family,” he said. “I don't know if I would be able to do it.”

The ECI had earlier declared September 1, 2025, as the deadline for filing claims and objections to the exclusions from the draft electoral rolls. The timeline for applications for inclusion has now been revised to the last day of nominations before Bihar’s assembly elections—the schedule for which is yet to be announced.

ECI spokespersons and Vinod Singh Gunjiyal, Bihar’s Chief Electoral Officer, did not respond to requests for comment. Pushpinder Kaur, Press Information Bureau’s spokesperson for the Election Commission, replied: “The message has been forwarded to Election Commission of India. Response awaited.”

This copy will be updated if we receive a response.

Our latest Sena project tracks how elites take over public spaces in urban India, and the price that’s paid by you. Click here to contribute.