‘Purity’ doesn’t bring peace: 2025’s warning for Bangladesh, Myanmar, Assam and Bengal polls next year

The empires whose civilisational glories nativists boast of were inevitably mosaics of peoples, cultures and languages.

Four upcoming elections are set to shape the politics and security of a region that sits at the strategically sensitive junction of India and China and directly affect the lives of a population larger than that of every country in the world barring India and China.

From December 26 until January 25, Myanmar will see its first, highly controversial elections since the military coup in February 2021 that overthrew civilian rule led by the National League for Democracy under Aung San Suu Kyi. In February, Myanmar’s neighbour Bangladesh is scheduled to have its first, also highly controversial, polls since the uprising of July 2024 that ended with the abrupt fall of the Awami League government led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. And finally, sometime in March-April 2026, the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal which border Bangladesh will have their next assembly elections.

These places – Myanmar, Bangladesh, West Bengal and Assam – are part of an interconnected geography that share long-intertwined histories. Events in one place have often had consequences for another down the centuries. With modern technologies of physical and digital communication, the potential for such consequential interconnections between events is now arguably greater than at any previous time. A thing happening in one place may swiftly influence events in another.

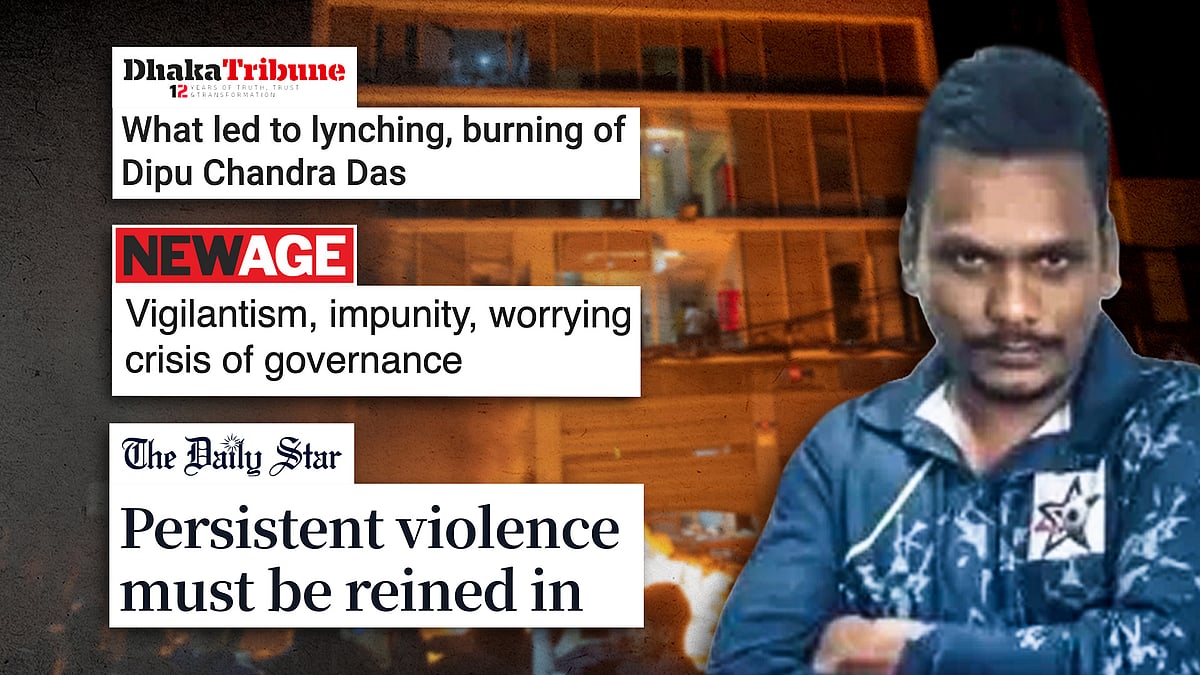

The “thing happening” could be the shooting of a politician such as Osman Hadi in Dhaka; it could be the killing of a Hindu man such as Dipu Chandra Das for alleged blasphemy elsewhere in Bangladesh. It might be the lynching of a “suspected Bangladeshi immigrant” somewhere in India, or the killing of Bangladeshi civilians at the border. It may even be a ratcheting up of pressure on the Myanmar junta at the International Court of Justice for genocide against the Rohingya people, more than a million of whom are now refugees in Bangladesh.

The ICJ will hear a genocide case against Myanmar for its repression of the Rohingya in January. This will bring renewed focus to the Arakan, from where the Rohingya have been forcibly evicted.

It is a place of current and historical significance for the broader region including Bangladesh and Northeast India.

The Arakan coastline along the Bay of Bengal is one where China and India both have competing investments and projects. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which mirrors the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to India’s west, terminates at the Arakanese port of Kyaukphyu. India, for its part, has long been investing in the Kaladan Multi-Modal Project that would open a route for landlocked Northeast India via Mizoram to the Arakan coast port of Sittwe.

Of all the places in Myanmar that have slipped out of effective control of Myanmar’s government since the outbreak of civil war in mid-2021, the Arakan is arguably the most significant. It is now a place that is effectively, barring a few towns, under the control of a local ethnic armed organisation, the Arakan Army. However, the crucial port of Kyaukphyu remains under junta control.

Both China and India have long maintained friendly relations with the Myanmar military junta but also engaged to differing and varying degrees with opposition groups including the ethnic armed organisations that have been at war with the junta over decades.

In the forthcoming national elections in Myanmar, prospects of any meaningful polling in the Arakan province are currently negligible. In the rest of the country where voting does occur, the elections will be largely farcical because the most important political party of Myanmar, the Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy, is formally “dissolved” and barred from contesting this or future elections.

Elections minus contenders

If elections proceed as scheduled, a similar farce will take place in neighbouring Bangladesh, where the Awami League is barred from contesting the forthcoming polls. While the party and its leadership had undoubtedly become highly unpopular with a large mass of the country’s people by the time Hasina was overthrown, it was still one of the two natural parties of power in Bangladesh, along with its rival the Bangladesh National Party.

Such parties tend to have deep and wide roots of support.

Imagine the Congress or BJP in India or the Democrat or Republican party in the US being forced out of the ballot in a national election; such an exercise would indisputably lack legitimacy. Unfortunately, in the cases of both Bangladesh and Myanmar, that is what is going to happen. In Bangladesh, it may be seen as payback for Hasina and her backers – meaning India – for the controversial elections in 2014 and 2018. While the BNP boycotted the 2014 polls over demands for elections under a neutral caretaker government, the 2018 elections were marred by mass arrests of BNP leaders and reports of ballot box stuffing to favour the Awami League.

This time around, the BNP and its erstwhile ally the Jamaat-e-Islami are poised to benefit from the not-level playing field from which their erstwhile tormentor has been kicked out.

The elections will also see the new National Citizen Party (NCP) emerging from the 2024 student-led uprising contesting for the first time, making it a choice between more change and a return to a semblance of “normalcy” for voters. Reports from Bangladesh indicate that fatigue with the unrest and “mob rule”, and the economic woes that have accompanied it, has set in by now. The BNP, newly energised by the return from exile after 17 long years of its leader Tarique Rahman, son of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, is the favourite to win if reasonably free and fair elections are held as scheduled. Despite its own internal divisions and history of corruption and excesses, it represents a return to normalcy and thus probably remains the most viable alternative to the Awami League.

As a centre-right party, it is also now the relatively “liberal” option, and potential gainer of a section of Awami League voters, because its principal rival for power is now the Islamist Jamaat.

Historically, the best-ever performance for Jamaat was in 1991, when it secured 12 percent of the vote. This time, it comes into the polls with a surge in its popular support, and powerful backers, domestic and international, who would like to see permanent change in Bangladesh. It could potentially arrive at a tactical understanding with the NCP and the current Muhammad Yunus led interim government, making it a serious contender.

In Myanmar, the sole contender for party of power after the so-called elections is the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the military’s proxy. This will pave the path for coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing to formally become President. His donning of civilian garb would not meaningfully change the status quo. The civil war, therefore, will continue.

The conflict in Myanmar between its Bamar-dominated heartland and minority ethnic groups has been protracted, dating back to the country’s origins as a modern state in 1948. The military’s loss of control in recent years over large swathes of territory despite widespread use of air power suggests that the formation of a federal union with greater autonomy for the provinces dominated by ethnic armed organisations is the only path to a lasting solution. This has been the longstanding demand of several ethnic minorities for decades, and is now also the demand of the alternative National Unity Government formed after the coup by opposition members in exile.

It is a solution that would leave the complicated knot of troubles in Arakan unresolved.

Conflating identity with belonging

There, the Arakan Army, while itself opposed to the junta and the Bamar majority, is also at odds with the Rohingya who it sees as outsiders in the Arakan. The Arakan Army’s base is ethnic Rakhine, drawn from speakers of Rakhine dialects, and primarily Buddhist. The Rohingya are mostly Muslim (there are Hindu and Christian Rohingyas too) and speak a language closer to the Chittagong dialect of Bengali. Like the Burmese governments of Aung San Suu Kyi and the military junta that toppled it, the Arakan Army also denies the existence of any community called Rohingya and simply refers to them as Bengali Muslims with origins in what is now Bangladesh. The Rohingya are viewed by all these disparate groups as Bangladeshi migrants.

It is a view that is in some ways similar to the one seen in Northeast India, and increasingly, in other parts of India as well, that conflates Bengali Muslim with Bangladeshi. Simply put, there is often an assumption that any Bengali-speaking Muslim rightfully belongs in Bangladesh. This notion sharpens when the person in question is visibly poor; a rich Bengali Muslim is rich first, and Bengali, Muslim, and/or Bangladeshi next.

The fear that vast hordes of immigrants from what is now Bangladesh would overrun Northeast India has been a dependable issue for politicians from Assam dating back to before the independence of India, to the first elections with limited franchise held under British rule between 1921-37. In time, these concerns about “demographic change” that emerged in a colonial context marked by communal politics morphed into a generalised anti-outsider sentiment that saw waves of mob violence in Assam and Meghalaya targeting local minorities including Marwaris, Nepali speakers, Biharis and others. The prime targets, however, were Bengalis, Hindus and Muslims alike. The local Hindu Bengali minority which was mainly Partition refugees from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) were also targeted locally as Bangladeshis and in many cases forced to move again.

The National Register of Citizens and Citizenship Amendment Act followed from there.

Now, the recent public release of a report into a massacre of East Bengal-origin Muslims that occurred in 1983 in Assam – the Nellie Massacre – by the Assam government of Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma after a period of 42 years suggests that the politics of “Bangladeshi” migration may be an important part of the governing BJP’s campaign leading up to the polls, because the focus is not on justice for the victims but on their presence in Assam.

Assam and Northeast India's “anti-Bangladeshi” politics, like that in Myanmar, historically has linguistic and ethnic dimensions apart from religious ones.

A more purely communal Hindu vs Muslim version of anti-Bangladeshi politics, taking off from the mob lynching of Dipu Chandra Das in Bangladesh, is already playing out in West Bengal as well.

There, as elsewhere in India, people's minds have been moulded by an unending drip of rumours circulated via social media that vast numbers of Bangladeshis have illegally infiltrated into West Bengal with the active connivance of secular governments.

Bengalis themselves cannot tell a Bengali and a Bangladeshi from a similar class background apart; there is no way to do so, short of looking at passports. However, this merely tends to give rise to the suspicion that all Bengali Muslims must be migrants from Bangladesh – and if they have Indian documents, then the veracity of the document itself becomes suspect.

It is sometimes said that Indian Bengalis and Bangladeshis can be told apart by the dialects they speak. This is factually incorrect. Partition and the ensuing migration of millions ensured that large numbers of people who spoke dialects from one part of Bengal ended up in another. There is a preference for certain words in Bangladesh — for example saying “pani” for water, or the way they tend to call people “bhaiya” or “chacha” rather than “dada” — but those preferences exist among Bengali Muslims from West Bengal too, particularly in border districts. Hindu Bengalis in Bangladesh, of whom there are still 13 million, similarly tend to say “jal” for water, like their counterparts in India, and would be likely to say “dada” rather than “bhaiya” in personal spaces.

However, the tendency to view all Bengali Muslims as migrants with origins in Bangladesh is now national in India…like it has long been in Myanmar.

The idea that everyone who speaks a language and shares a faith must be from the same place is, of course, utter nonsense. It is a worldview that betrays deep ignorance of the history of global migration.

All Nepali-speakers are not from Nepal; there is a large Nepali-speaking population who are Indians and whose forefathers going back generations were Indians. All Tamil speakers are not from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu; there are huge native Tamil populations in several countries including Sri Lanka and Singapore, where it has official language status, and Malaysia, where it is a recognised minority language. All Bhojpuri speakers are not from Bihar or Uttar Pradesh. There are large Bhojpuri-speaking populations in Mauritius and Guyana. All Hindi speakers are not from India either; there is a Hindi dialect spoken in Fiji.

Do the diasporic populations produced by colonialism now belong in their new homes?

The association of language and religion with imaginations of nation and nation-state have been hugely problematic for the world in recent times.

This is only going to increase. Whether it is a small state such as Manipur or a large region encompassing parts of South and Southeast Asia, the problem of conflating linguistic and religious identities with exclusive territories and then proceeding to try and cleanse such imagined territories of “outsiders” is perhaps the worst problem that the resurgence of nationalisms worldwide has created.

It is an intractable problem, built into a global architecture whose basis is nation and nation-state and whose preferred form of governance is democracy.

The idea that a group of people with a particular language, religion and ethnicity constitute a nation and are the rightful owners of their nation-state mixes uneasily with the anxiety among dominant groups that their majority status, and hence their dominance, may in time be challenged due to the in-migration of outsiders. This is true of sub-state units too; Manipur and Assam are examples.

From USA to Europe to India, Myanmar and as far east as Japan and Australia, this anxiety produces the same nativist reaction everywhere: the notion that “this land is our land”, and “we” who rightfully belong are defined, in every case, on the basis of some combination of national language, religion and race; e.g. white, Christian America and Europe, Bamar Buddhist Myanmar, Hindi Hindu India, Muslim Bengali Bangladesh, etc.

Naturally, such a conception of the land has no space for minorities who are seen as rightfully belonging in some other homeland or in no land at all – even if they have been in the same place for generations or centuries. Sometimes, the idea of indigeneity is invoked to justify the exclusion; only the “indigenous” rightfully belong.

Concepts often become clearest at their extremities.

The idea of a national race and what it means to create a “pure” national homeland cleansed of “outsiders” is nowhere clearer now than in Israel and Gaza, where the Israelis, whether white, black, brown or of the East Asian racial type such as the Bnei Menashe from Mizoram and Myanmar, claim indigeneity.

The genocide case against Myanmar in relation to the Rohingya will have implications for Israel and Gaza too.

If the rest of the world is to avoid the replication of a world war, not in the form of one terrible war between superpowers but as a thousand terrible civil wars and genocides of countries with their own “outsider” minorities, the “civilisational” notion conflating nation and nation-state with one exclusive ethnicity, religion and language must be put to rest.

The empires of bygone eras whose civilisational glories nativists boast of were inevitably mosaics of peoples, cultures and languages.

Countries that try to erase internal diversities in a quest for purity can never be at peace with themselves.

The writer is the author of Northeast India: A Political History, published by Hurst in the UK and HarperCollins in India, and co-editor of two volumes on the issues of identity and belonging.

Twenty-five years have transformed how we consume news, but not the core truth that democracy needs a press free from advertisers and power. Mark the moment with a joint NL–TNM subscription and help protect that independence.

‘Arrests reactionary, culture of impunity’: Bangladeshi dailies slam govt over Hindu worker’s lynching

‘Arrests reactionary, culture of impunity’: Bangladeshi dailies slam govt over Hindu worker’s lynching ‘Travesty of justice’, ‘Revenge trial’ : Editorials on Sheikh Hasina's death sentence verdict

‘Travesty of justice’, ‘Revenge trial’ : Editorials on Sheikh Hasina's death sentence verdict