Learning to linger: On longform writing in a time of noise

In a profession built on urgency, what does one gain by slowing down?

A large part of my journalistic life has been in Delhi, a strange city full of people trying to find their own space, their own words, their own life. Very early on a senior journalist friend gave me a piece of advice that I held on to – “Be diligent, don’t question the hours, stick to the style guide, travel whenever you’re asked to, some seniors do know better than you,” she said and added “Spend your time in the trenches. Then do what you want.”

And for six years I did the daily reporting: the elections, the political upheavals, sexual violence, murders, riots, militancy, agricultural issue and more.

But then, a certain discomfort began to creep up on me. Even as the news kept breaking, I started getting more interested in stories that happened years ago. I found myself fixated on certain characters. I was curious about certain incidents that shifted society.

I caught myself irritated with having to compulsively keep up with the breaking news cycle, of needing to know everything that was happening everywhere.

That said, I am acutely aware of the labour that goes into producing the news every single day. Scores of reporters – most often underpaid and overworked – traverse the country to give life to that slim sheet of paper that lands on our doorsteps each morning. People are informed, offended, and validated. Governments shift. Decisions are made. Politicians fall. Columnists argue.

My first response to this growing discomfort was shame. So for a long time, forget saying it out loud, I refused to even think about it. I worried about judgement, but more than that, about being misunderstood. Because it had begun to dawn on me that unlike many of my colleagues, I could not find it in me to care about everything equally. I was deeply moved by women, and I wrote with urgency when it came to their lives. For much else, I had to push myself.

That push is necessary early in one’s career. But after a point, I felt like if I didn’t find more meaning in my work, I would begin to resent it. And that’s unfair to the people we write about and the organisations we work for.

We live and work in deeply polarised times. One quiet but persistent fallout of working in such an ecosystem is the loss of play – the kind that allows one to experiment with language, form, and craft.

This is when I made a decision to experiment with longform journalism – a choice made possible by The News Minute and Newslaundry – I realised two things.

First, longform is possible only because of the daily grind of reporters. Their relentless work feeds analysis and depth. But everyone need not be cut out for it.

Second, longform is a lonely process that demands absolute honesty. You cannot pretend your way through ten thousand words. That many words will expose you. You have to write about things you genuinely care about – and for me, that honesty had to begin in the smallest details of my life.

I started reading fiction and longform reportage. I read about women across eras, about worlds that existed long before mine. I realised that much of what we experience has already happened – repeatedly, across time and geography. Much of what we write has been written before.

Even political exhaustion is not new. We are not alone in our fatigue, our resource crunch, or our struggle to nurture craft.

Reading gave me hope. And hope is a necessity to do whatever one does every single day, most often without immediate impact.

For me, hope lies not always in content, but in form. In the shape of sentences. The magic was not in saying something new, but in saying something meaningful enough to move someone.

And slowly I started to find my way through longform reportage. I began producing fewer but more in-depth stories.

In the last two years, I followed the stories of two women from my home state Kerala. One, a two-part story on a top female actor who was sexually assaulted by six hired criminals. Acquitted actor Dileep had been accused of masterminding this crime. A case which had triggered a Weinstein-scale movement in Kerala.

Two, a nun who had accused Bishop Franco Mulakkal of rape in 2017, the first in India. The bishop was eventually acquitted, but the nun continues to live a life of isolation and subjugation. This is the first time in 11 years that the nun chose to speak to a reporter.

No governments fell because of the longform reports my editors enabled me to do. No politicians resigned. No policies were rewritten. And some male journalists did wonder out loud when I would begin doing “real journalism”.

But hope arrived in quieter ways.

A young woman wrote to say her father finally understood the problems with the Dileep case after reading our story. A Catholic man who had struggled with his faith said that he felt seen after our report on the Franco Mulakkal case. A student told me their teacher held a classroom debate on gender based on our coverage of the actor assault case.

Two years into longform journalism, I am focusing on my craft, finding my own ways of telling stories. I am now more at ease not knowing about everything, everywhere but learning to be more rigorous with stories I’m focusing on.

As a new year dawns, it will bring new hopes, new stories and problems. But I’m going to be looking for stories that we can revisit deeply. If you have any ideas or cases that you think deserve to be re-looked at please do write to me at nidhi@thenewsminute.com.

Best,

Nidhi

P.S: Not accepting comments regarding em dashes and AI.

At Newslaundry, we believe in holding power to account. Our journalism is truly in the public interest – funded by our subscribers, not by ad revenue from corporations and governments. You can help. Click here and join the tribe that pays to keep news free.

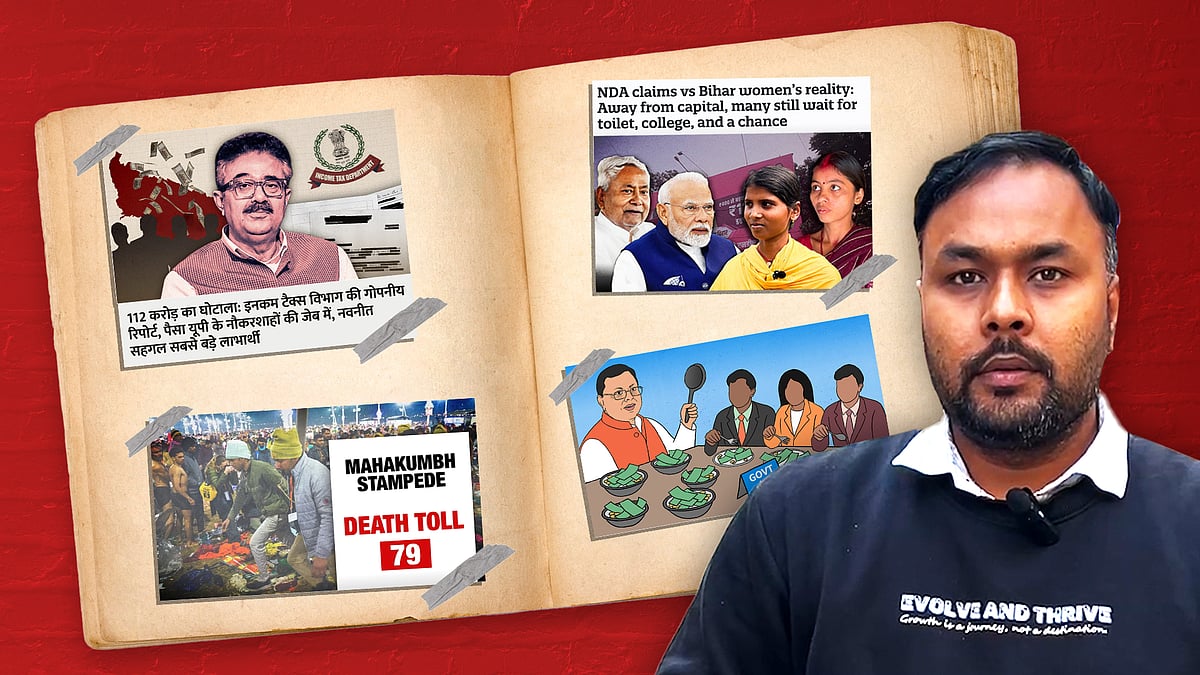

Kumbh Mela lies, Rs 112 cr embezzled, and a mother’s tears I can't forget

Kumbh Mela lies, Rs 112 cr embezzled, and a mother’s tears I can't forget Cyber slavery in Myanmar, staged encounters in UP: What it took to uncover these stories this year

Cyber slavery in Myanmar, staged encounters in UP: What it took to uncover these stories this year