He couldn’t let the ‘worst performer’ in his team be axed. So, this editor quit himself

For eight years, Pratik Bandyopadhyay headed the sports beat in East India for a major national newspaper.

What would you do if your boss asked you to assess your team members and single her the “worst performer” to be sacked? It is tough, but chances are that you would oblige. Layoffs are not an aberration in private organisations. And since the Covid-19 outbreak, they have become all too common, including in the news industry.

But Pratik Bandyopadhyay, the regional sports editor of a major national daily, chose differently. Unwilling to present a head to be axed, he sacrificed his own job.

“I was heading a small team of five, including myself. How could I pick out the ‘worst performer’ when all have worked so hard? So instead, I resigned myself,” Bandyopadhyay, who is based in Kolkata, told Newslaundry.

After Bandyopadhyay took over in 2012, he handpicked and built the team. Over the next eight years, he said, their team brought stability to the newspaper’s sports beat. “We covered multiple sports across east India, apart from writing about international events. Our stories contributed to all editions of the newspaper,” he said.

But that clearly wasn’t enough. Citing the economic fallout of the coronavirus crisis, the newspaper decided to cut its staff size, and the tiny sports team became an easy target.

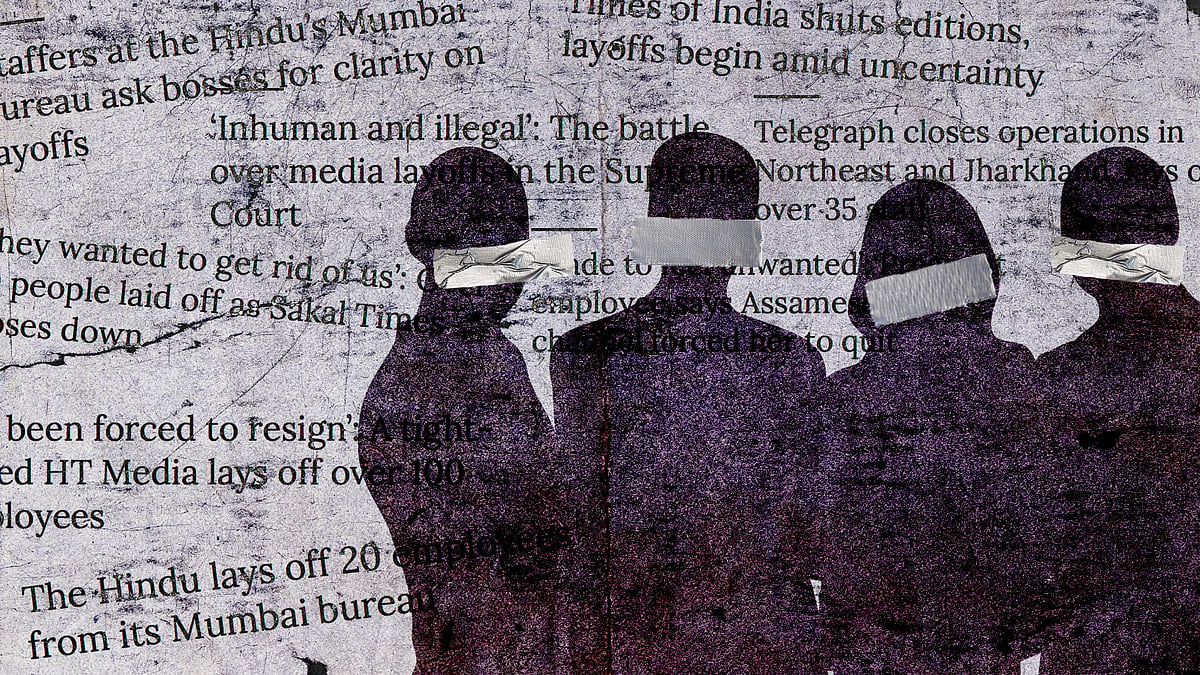

With the pandemic surging, media organisations across the country have felt the heat. Predicting dips in ad revenues, hundreds of journalists have been either fired or asked to resign by some of the biggest names in the industry. Salaries have been slashed too. Bandyopadhyay’s organisation, like many others, began with salary cuts, and followed it up with a layoff plan.

If anyone had to go, it had to be him

It began in April.

An email was sent to employees and that month’s salary was cut in varying degrees. On April 30, Bandyopadhyay’s take-home amount of Rs 94,000 was cut by about Rs 14,000. Junior colleagues on his team received pay cuts ranging from Rs 3,000 to Rs 8,500.

“The message was loud and clear. I could sense there would be downsizing of staff after this,” Bandyopadhyay said.

He began hearing rumours that the human resources department would target the sports team. This was clear by the end of April, he said, when the sports section across editions had shrunk to one page — even less, at times. Then, in the first week of May, Bandyopadhyay received a phone call from a senior editor based in Delhi.

The editor told him the company’s plan: that the head of each sports department would be required to identify the “worst performer”. What would happen to that employee, Bandyopadhyay asked.

“We will fire as part of our restructuring plan due to the current financial crisis,” the editor replied. “Or, at best, the person would have to agree to a 50 percent pay cut on the already reduced salary.”

But Bandyopadhyay had already made up his mind. If anybody had to go, it had to be him. It was a decision he had reached after a discussion with his wife. Much to the editor’s surprise, he announced it on the phone call. His reasons were simple, he said. “Unlike me, the others in my team had many liabilities. My wife has a government job and I don’t have any loan.”

Bandyopadhyay’s wife is a teacher at a government higher secondary school in Domjur, a town in Howrah district. She makes nearly Rs 50,000 per month. They have one daughter, a Class 3 student, and live in a house they own in Konnagar, a suburb of Kolkata. Bandyopadhyay’s mother lives in a nearby apartment on her own.

The Delhi editor asked him to reconsider and talk it out with the regional editor of the newspaper in Kolkata. Bandyopadhyay complied, and the regional editor asked him to wait, and not rush into a decision. The regional editor also asked for some time to see if the situation could be managed without Bandyopadhyay resigning.

But a week passed, and there was no word.

When Bandyopadhyay asked the regional editor again, the latter laid out a harsh plan: If Bandyopadhyay continued in his job, the salaries of employees would be cut — not only for the sports team, but for some others as well. Even then, somebody would have to be sacked.

“I said there was no need for all that. And sticking to my decision, I resigned on May 16,” Bandyopadhyay said.

But the charade continued. The editor telephoned Bandyopadhyay and said he would not accept his resignation immediately. A more generous severance package would be worked out for Bandyopadhyay, the editor added, offering two months’ pay as severance instead of the standard one month’s. There was no communication for another week and when Bandyopadhyay contacted the editor once more, he was asked to wait until the company asked him to resign.

“He said it would give me a better settlement. I got angry because it wasn’t something I was looking for. I had taken a moral decision and made it clear to him,” Bandyopadhyay told Newslaundry. Following this conversation, the Kolkata-based editor accepted his resignation.

Accordingly, Bandyopadhyay’s stint at the organisation ended on June 15.

‘Profits over ethics’

Starting out as a trainee at the Statesman in Kolkata in June 2005, Bandyopadhyay has been a sports journalist for 15 years. He joined his last job in March 2012 as a chief copy editor. At the time of his resignation last month, he was working as a deputy news editor, digital content.

His office shift was from 4 pm to 11.30 pm. For eight years, he made the long journey to his office in Kolkata every afternoon. The first part of his commute was a local train from Konnagar to Howrah, where he would catch a bus to the office. After work, he would reach home well past midnight.

There were several high points in his last job, Bandyopadhyay recalled, the first achievement being the stabilisation of the sports desk with fresh updates. When the beat had been handled by the Kolkata edition’s sports team, the latest news wasn’t passed on to other editions, which often upset readers.

“For example, there is a big following of football in the Northeast. But when they received stale news about, say, the [English] Premier League, they would not like it,” Bandyopadhyay said. That changed when his team took over the East India sports beat, he added.

Another significant moment was initiating the full-fledged coverage of Ranji Trophy matches of states other than Bengal. As the paper began reporting on matches played by teams like Assam, Jharkhand and Tripura, the eastern editions of the newspaper drew in readers.

Every year, the busiest months for his team would be between late September and late February, Bandyopadhyay said. During this period, several high-profile tournaments like the Ranji Trophy, the Indian Super League, and the Hockey India League took place in different cities in the region. Occasionally, there would be an international cricket match or two as well.

“We would churn out stories constantly. Often, I would run short of people to man the desk in Kolkata as some would be out reporting,” Bandyopadhyay said. “So, none of us could take any leave during this period.”

The team, therefore, was already overworked, according to him. Yet, they never complained and continued to work diligently. “Despite such hard work over the years, how could the organisation just decide to sack one of us?”

The layoff plans across media organisations, he said, reflects a preference for profit over ethics. Bandyopadhyay pointed out that many of these organisations, including the one he worked for, had big cash reserves that could have been used to tide over temporary adverse business climates, like this one, without affecting employees. “But nowadays, editors have become managers. They follow typical, hardcore corporate practices without much sympathy for the juniors.”

What lies ahead for Bandyopadhyay now? He has no immediate plans to join any other organisation, and is mulling over working as a freelance writer.

More importantly, he has to finalise the manuscript of his third book, a Bangla novel, and find a publisher. Bandyopadhyay has already published two books of poetry in Bangla: Khata Chnera Nauko, published in December 2014, followed by Kabir Bhoyer Bhetor in January this year.

“Currently, I just want to focus on my own writing. This is something that gives me immense satisfaction,” he said.

The name of Bandyopadhyay’s former place of work has been kept anonymous at his request.

***

The media industry is in crisis. Journalists, more than ever, need your support. You can support independent media by paying to keep news free. Because when the public pays, the public is served and when the advertiser pays, the advertiser is served. Subscribe to Newslaundry today.

There's something rotten in the state of Indian media. Public funding might help

There's something rotten in the state of Indian media. Public funding might help By staying silent on layoffs and pay cuts, Indian editors have failed their colleagues

By staying silent on layoffs and pay cuts, Indian editors have failed their colleagues