Win for transparency: Parliamentary committee recommends mandatory annual reports for high courts

Even though the SC is not the best role model in disclosures in its own annual reports.

Last week, a committee – officially the Department Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, and Law and Justice – tabled its 133rd report before Parliament.

Titled Judicial Processes and Their Reform, the report focused on reforming the Supreme Court and high courts, recommending a range of measures to improve not just the efficiency of the higher judiciary but also the lack of diversity among judges appointed to the courts.

The report is a very welcome development since the higher judiciary has traditionally been insulated from any outside scrutiny. It is also remarkable that the committee tries to locate its prescription for reforms with the framework of judicial accountability as opposed to the usual recommendation of providing the judiciary with more resources.

One particular reform suggested in the report is the need to mandate the publication of annual reports by the higher judiciary, documenting their performance. This borrows extensively from recommendations we made last year. We had argued that annual reports are an important tool of accountability for public institutions. The ministry of parliamentary affairs has published instructions for various government departments relating to the preparation of annual reports that are eventually tabled before Parliament. But these instructions do not apply to the judiciary, which is independent of the government’s control.

In the absence of a legal mandate, not all high courts publish an annual report. But even the ones that do tend not to reveal much in said reports. The exception to the rule was the Orissa High Court’s annual report from June 2022, which was surprisingly reflective. It not only accounted for the work of the court on the judicial side and achievements of the state judiciary, but it also shed light on administrative work.

For instance, the report documented that the administrative committee dealing with appeals filed by judicial officers against disciplinary orders, dealing with 13 out of 40 appeals in the year. This information helps us understand the administrative workload of the high court judges.

It also pondered on reasons for delays in district courts and found that uneven distribution of caseload between judges, the propensity of the high court to ‘stay’ proceedings, and unavailability of witnesses are the major reasons affecting delay.

Most importantly, the report demonstrated that the Orissa High Court and especially then Chief Justice J Muralidhar had attempted to supply meaning to what is otherwise a perfunctory exercise in the judiciary.

While many high courts don’t see the value of publishing annual reports, it should be noted that this was not always the case. In the early decades after independence, the Allahabad High Court published reports that contained granular judicial statistics that described the nature of litigation in the court at the time. These were used by scholars to publish research on Indian courts. For reasons unknown to us, this laudable tradition was abruptly abandoned sometime in the 1970s. It is time to revive it and go beyond bland statistics to instead reflect on the trends and reasons underlying the statistics.

An annual report should ideally cover different aspects of the institution’s functioning, instead of limiting itself to judicial work. Some self-reflection by high courts can go a long way in improving their judicial efficiency and the efficiency of the district judiciary they administer.

The parliamentary committee recommends that the Supreme Court direct the high courts to publish annual reports and to also suggest the items to be included in it. While the committee may have made the recommendation with the intention to ensure uniformity amongst high courts, this is a problematic recommendation since, as per the Constitution, the Supreme Court does not have administrative control over high courts.

Additionally, the Supreme Court itself is barely a role model when it comes to disclosures in its annual reports. Although the apex court has been publishing a report since 2003-04 (with a gap between 2009 and 2013), the contents of its reports leave much to be desired. It typically contains profiles of the sitting judges and a skeletal description of the court’s judicial performance. It also provides a general overview of court administration, changes made to the court building, and initiatives undertaken in the year including those in the realm of legal services, training and alternative dispute resolution. It is followed by a crude snapshot of the statistics of each high court.

The report is conspicuously silent on its internal administrative functioning and self-assessment on its performance in the preceding year. Its priorities lie with exalting the position of the judges and the institution. It does not dwell upon the issues that plague the performances of the judges or challenges faced by the registry.

The parliamentary committee is also being naïve in expecting that the higher judiciary will start publishing useful annual reports of its own volition, given that their record on transparency under the Right to Information Act has been tragic. The higher judiciary has persistently ignored the obligations of public authorities under the Right to Information Act and created exceptions for itself while demanding transparency from the executive.

Given the higher judiciary’s hostility towards meaningful transparency, it is incumbent upon Parliament to legislate on the requirement to publish an annual report and provide a list of mandatory disclosures to be made by each high court. It should necessarily mandate detailed budgetary disclosures so as to ensure financial accountability. Similarly, the Chief Justice of each high court should be required to provide reasons and a roadmap for dealing with judicial delays. And finally, the report should also be presented to the relevant state assembly which pays the salaries and expenses of the high court in question.

Asking for greater transparency from public institutions is not offensive to the principle of judicial independence. And hence Parliament should not hesitate to enact a law on it.

Chitrakshi Jain is a legal researcher. Prashant Reddy T is a lawyer.

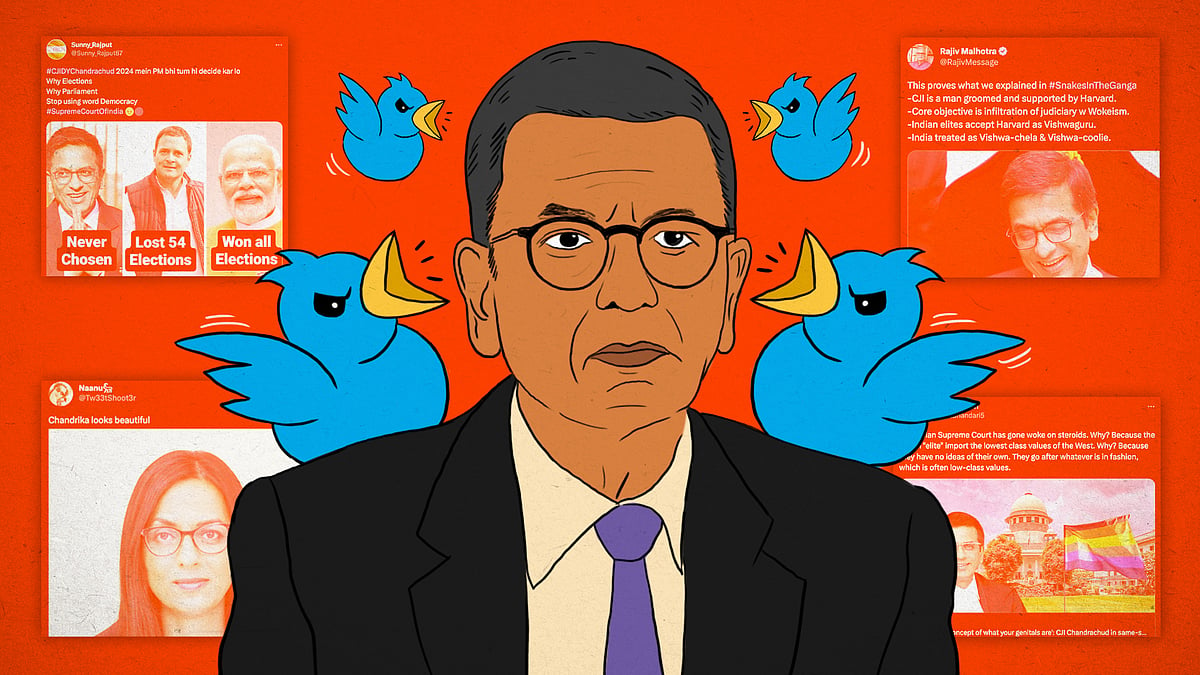

Anti-Hindu, woke feminist: Inside the unprecedented online trolling of CJI Chandrachud

Anti-Hindu, woke feminist: Inside the unprecedented online trolling of CJI Chandrachud