The Indian rightwing is celebrating the Washington Post layoffs. Here’s why that’s terribly idiotic

Jeff Bezos didn't sack your ‘anti-India’ villains because their ‘agenda’ failed.

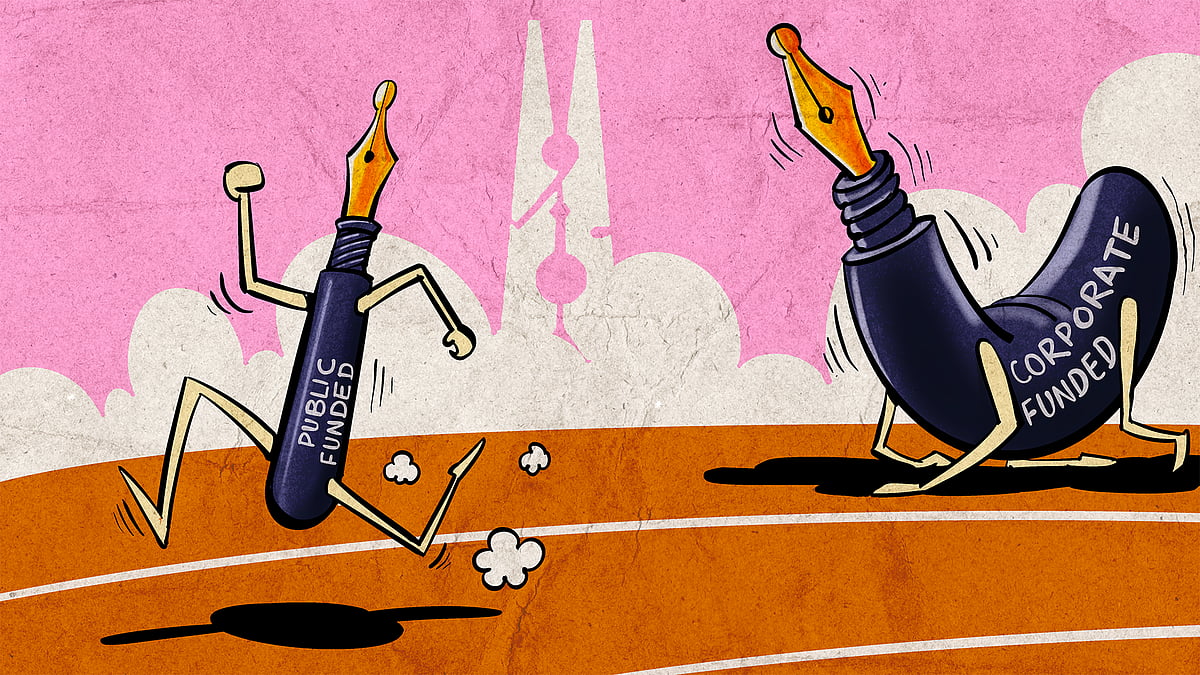

There are several serious conversations to be had about the Washington Post layoffs – about money, sustainability, the slow cannibalisation of news by tech platforms, and what journalism is now expected to do in 2026.

Those conversations are taking place in newsrooms and in journo WhatsApp groups.

They are not taking place on X.

On X, the layoffs have become a small festival. Rightwing commentators, especially those high on vishwaguru TV fumes, are delighted. A ‘liberal’ American newspaper has been brought down. Serves them right. Agenda journalism failed! Ha, that’s Karma!

What is being said here is so wrong that it demands correction. Even if X is the worst possible site for public reasoning, journalism is too important to be left to people who have only the vaguest idea of how news is produced, funded, or sustained.

The laziest claim doing the rounds is that journalists were sacked because their agenda failed.

The Washington Post did not shut bureaus because its reporting from India or elsewhere was bad, biased, or ineffective. Large corporations do not make decisions that way. They shut bureaus when owners lose interest, patience, or money – usually all three.

If journalistic quality were the measure, half of Indian television would have disappeared long ago.

The idea that Jeff Bezos woke up one morning, skimmed a few India datelines, and concluded that the agenda was not working is absurd. Sections are being cut because he no longer wishes to subsidise a global newsroom that does not align with his priorities. If there is any doubt about what those priorities are, the Melania documentary should settle it.

To claim that the Post did no meaningful journalism from India over the last decade is simply untrue. It pursued stories that mattered – Nijjar, Adani, surveillance, Bhima Koregaon arrests, the BJP’s online machinery. These stories questioned the Indian government at a time when much of the domestic media was engaged in ritualised praise.

The work was not perfect. It was sometimes blunt, sometimes schematic. But it was not irrelevant.

The closure of a bureau does not prove that its journalism was useless. It proves only that it is no longer valued by the owner. Poor reporting, in any case, cannot be an argument for the abolition of newsrooms.

This brings us to the deeper irritation many of our rightwing luminaries have with foreign correspondents. I must admit I have shared some of this irritation.

I have rolled my eyes at the 200th monkey menace story. I have wondered why a witch-burning from a village somewhere in eastern India will reliably find its way to an NYT front page, as though this were the central fact of contemporary India.

This is not a plea for Modi-style triumphalism. But must India always appear as the land of spectacle – of magic, mystique or the grotesque?

Part of the problem lies with the foreign correspondent’s life in India. It is unusually insular. Many operate within diplomatic enclaves, socialise almost exclusively with one another, and mistake access to India’s elite for understanding India.

Stringers who are supposed to help them reinforce this. They learn quickly what sells and repeat it: Yeh flavour chalta hai. I once knew a fixer in a north-Indian town who escorted the same goras to the same people, same stories, for the same visuals, again and again. It worked. No one complained.

There is also the genuine difficulty of persuading foreign editors to care about India stories that are not ‘exotic’. In this regard, the Financial Times and The Economist stand out for having kept pace with India’s economic and political shifts without resorting to caricature.

But criticism of foreign writing on India – and we have criticised it since Gandhi – cannot become an argument for its disappearance.

Foreign correspondence does not matter because it is immaculate. It matters because it creates an external record. It documents what domestic media cannot, or will not, especially when power turns adversarial. Or it may quite simply spotlight what we local journalists have accepted as the norm.

Disagreement with coverage is not a case for erasing it. By that logic, every bad story would be a vote against journalism itself.

I get the frustration in noticing that India appears in foreign press mainly through stories of violence, anarchy or utter destitution, while China is discussed in terms of economics and geopolitics. But this discomfort should be directed inward, after switching off anchors who insist that we are already a world power.

The world is not as interested in India as we like to believe sitting in New Delhi. Something Anjana Om Kashyap appeared to discover the hard way when she flipped through American newspapers during Modi’s 2021 US visit, only to realise there was barely anything to flip through. Analysts have written enough about why India failed to become the elephant that would take on the dragon. Even global institutions that want India to succeed frame their praise carefully. The IMF and World Bank routinely flag fragile consumption-led growth and rising inequality. India’s economy is described as promising, resilient, improving – never transformative.

This is why India rarely features in global coverage as an economic force reshaping the world. China appears in stories about supply chains, technology, geopolitics and power. India appears sporadically, often through politics, social conflict or spectacle.

The outrage this provokes at home is disproportionate. It is easier to accuse foreign media of ignoring India than to accept a simpler truth: We aren’t the toast of the world as we’re being fed by nightly propaganda channels.

News doesn’t make money. Let it die.

This is the bleakest conclusion. News is no longer profitable. The platforms that once sustained it are weakening. Search is declining. AI is consuming attention. And the wealthiest owner a major newspaper has ever had shows no appetite for imagining a future in which journalism survives without substantial returns.

If Bezos cannot be bothered to solve this problem, it tells us how expendable news has become. Earlier media owners saw newspapers as institutions. New money sees them as assets. None of this is reassuring.

It may create room for smaller, nimble organisations. Or individuals. Or it may create nothing at all. But let us stop with this idiotic idea that this is some sort of a moral reckoning for bad journalism.

It is not.

Billionaires don’t have your back – whether it’s Bezos in Washington or someone else in Delhi, profits will always come before the public, and we’ve spent years reporting exactly what that does to newsrooms. The only real counterweight is you: subscribe, support independent journalism like Newslaundry, and help us prove that readers together are more powerful than any billionaire.

Paisa and power can’t protect journalism: Why readers are the only safety net that works

Paisa and power can’t protect journalism: Why readers are the only safety net that works From Watergate to watered-down: Every Indian journalist should read this piece

From Watergate to watered-down: Every Indian journalist should read this piece